By: Samantha Kummerer| Bond LSC

It takes a lot of time and patience to be a scientist. This is something that first-time researcher Natalie Hickerson quickly discovered.

“A lot of the time things are so small. I mean you’re using such tiny volumes of DNA that you can’t see anything happening,” said the undergraduate biochemistry major.

For some, this uncertainty pair with long lab hours and multiple trial and errors would be frustrating. Hickerson, however, put in the time and asked the questions, which led her to discover the rewards of research.

“You try something a few times and it wouldn’t work and then you change one thing and suddenly it works and you get results and it was just very exciting, like ‘wow what I’m doing is real,’” she said.

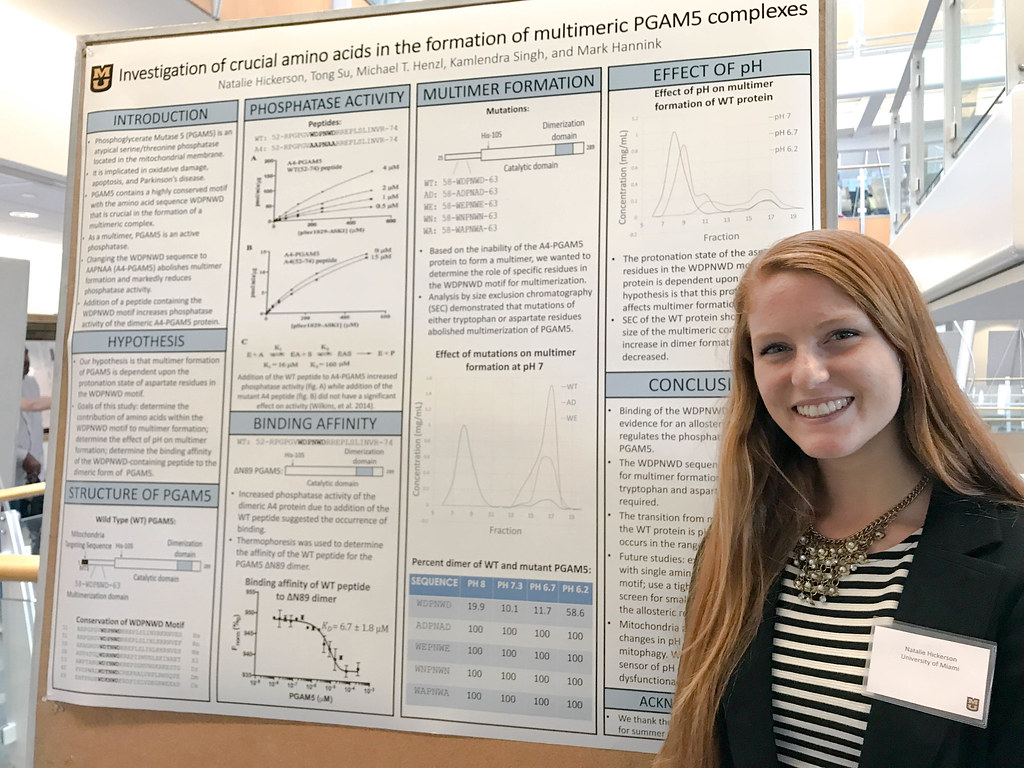

Hickerson attends the University of Miami but worked as a research intern in Mark Hannink’s lab in the Bond Life Sciences Center this summer. She said she chose the University of Missouri because the program was well rounded and fit with her major.

Hannink said while Hickerson entered the lab not understanding everything, she wasn’t afraid to ask questions and that helped her catch on fast.

“What makes a scientist different is that you are an active generator of new knowledge. Instead of being a passive consumer of existing knowledge you have to become an active producer of new knowledge,” Hannink said.

The Missouri native spent two months creating new knowledge on PGAM5, an important protein involved in many mitochondrial processes and cell death.

Hickerson began by intensely studying the protein at its most basic level to determine how and why it works the way it does. Part of this process was comparing different mutations of the protein.

Previous research shows how understanding the sensitivity of PGAM5 and its changes in the cell could help in nerve-degenerate diseases like Parkinson’s and ALS. Individuals suffering from those diseases experience a loss of function or mutation in some proteins.

Part of Hickerson’s initial research aimed at figuring out what signal activates PGAM5 in a cell. A better knowledge of that process will help scientists understand how pathways function and turn off during nerve-degenerative disease.

Hannink explained if a pathway is defective, activating a different pathway may function as a type of therapy.

After months of long hours, Hickerson discovered by changing the pH levels, PGAM5 can be switched from inactive to active.

“We had suspected it to be the case but the data she provided really helped demonstrate that was true,” Hannink said.

While Hickerson is headed back to Florida to continue her pursuit of biochemistry, her findings will continue to be advanced this fall in Hannink’s lab.

“There’s a lot more to be discovered with what we were doing,” Hickerson said. “A lot of the stuff we were doing this summer was new ideas and just developing deeper knowledge on things they’ve discovered in the lab previously. So, I was looking deeper into what they already started and we did find some new things so it was neat.”

She said her experience this summer inspired her to get more involved in undergraduate research.

“It definitely gave me a much better understanding of how to work in a lab and just basic lab techniques. The overall research project gave me a lot of good foundation for that,” she said.

As Hickerson continues to learn about research, Hannink said it’s an ongoing process that he is still a part of.

“I’m doing the same thing all the time that they are learning to do,” he said. “There’s this dynamic and that active learning process also challenges me to becomes a better scientist as well.”