Growing up on farm in Brazil, Fernanda Amaral often wondered why her father had to treat the soil with nitrogen fertilizer between growing cycles. She questioned why the soil wasn’t enough to consistently provide crops the nutrients they needed to grow and flourish.

Amaral remembers her father explaining soybeans take a lot out of the soil, leaving nothing behind for the next batch of crops. So, he needed to artificially treat the soil with chemical fertilizers to continue the harvest cycle, maintain his business and support his family.

“I used to go and help him harvest and I was always amazed by the process. I have two siblings, and for us it was very fun to watch,” Amaral said.

As she progressed through her undergraduate degree at the Federal University of Pelotas and into her Ph.D. program at the Federal University of Santa Catalina, Amaral realized the enormous cost and environmental disadvantages of nitrogen fertilizers.

“I wanted to understand the process of fertilizing soil and became interested in how we can improve the quality of it without spending so much money to produce it,” Amaral said. “I was always wondering why the soil wasn’t already naturally good enough.”

Her neighbors, who owned a farm the same size as her family, had to spend half of what they were making just to purchase nitrogen fertilizers. She remembers thinking “there has to be a better way.”

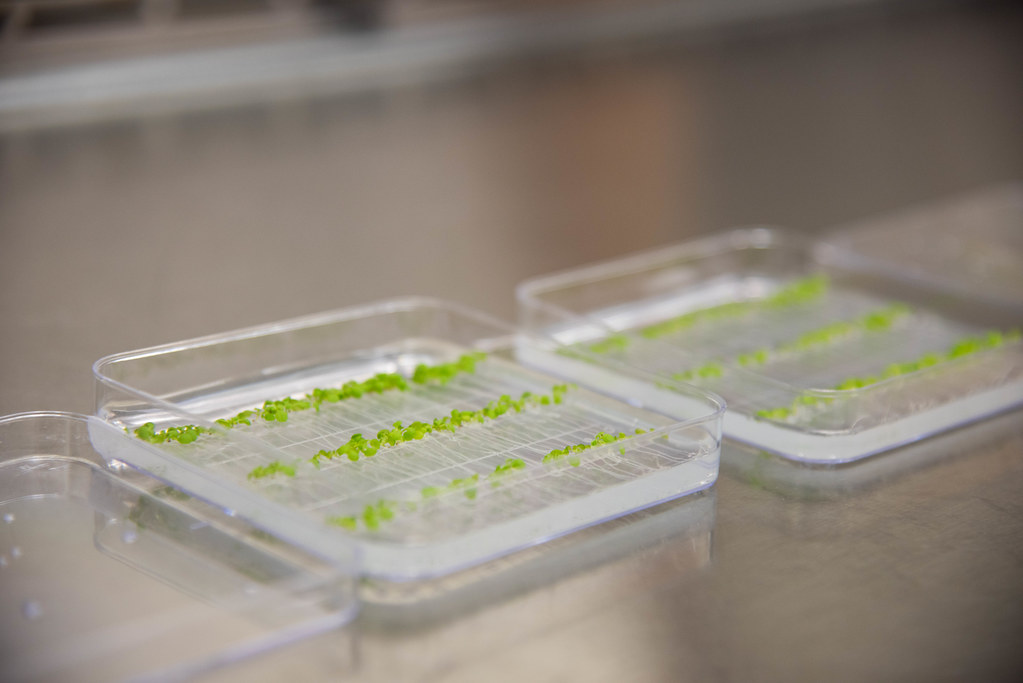

As a post-doctoral researcher in the Stacey lab, Amaral works with plant microbe interactions and focuses on the genes that are triggered by beneficial bacteria in plants. Some plants, such as soybeans, form root nodules when associated with bacteria. In turn, the nodules release nitrogen for the plant, which helps them grow healthier, produce stronger roots and yield more seeds.

She’s trying to understand how plants take advantage of the bacteria found in soil, which genes in the plant are involved, what’s in the bacteria that makes the mechanism work and how bacteria recognition happens in soil.

Amaral works with a grass model plant, which does not nodulate in response to the presence of a bacteria, making it more difficult to study the mechanism. But understanding the interaction at this basic level helps researchers compare what they know about the interaction to crops in the field.

This research could one day mean creating cheaper, more environmentally friendly bacteria-based fertilizers on an industrial level.

Unlike nitrogen fertilizers, non-pathogenic bacteria-based fertilizers are natural and don’t have the potential of water contamination.

Before her post-doc, Amaral spent one year in the Stacey lab as a visiting scholar as part of the Science Without Borders program, funded by the Brazilian government.

“I was drawn back to the lab because people were very nice,” Amaral said. “It’s a big lab compared with my former lab in Brazil. We have a very international lab and there are a lot of people from different cultures, so I’m always learning about other countries.”

Now, when she talks with her dad, Amaral finds he understands the results of scientific processes in the field, such as taller plants and green leaves after fertilizing the soil, which is a fun entry point for her to talk about the scientific mechanisms behind those results.

“When I talk to my dad about the technology, he has a general idea of what it is. He has so much knowledge of the fieldwork that sometimes even though he doesn’t know what the technology involves, he recognizes the outcomes of using those technologies in the field,” Amaral said.

Looking to the future, Amaral plans on wrapping up her last research project within the next 10 months. She hopes to work at a company in the agriculture industry that has a good mission and aims to help farmers improve production and reduce costs.

“Everything that starts in the seed ends up on our table. I want to do whatever I can to make a small difference,” Amaral said.