By Samantha Kummerer | Bond LSC

The Proteomics Center runs on proteins.

This research core facility is like a small business and is situated in the Bond Life Sciences Center. It has helped improve agriculture, opened doors for new medical applications and lead to greater insight into human diseases.

Proteins are some of the most plentiful and common building blocks of all living organisms, making structures in cells but also are key to antibody defense, enzymes to carry out chemical reactions and as messengers to coordinate biological processes.

This complexity makes an essential building block far from simple.

Figuring out what proteins exist and how they function is key to many experiments and that’s where Mizzou’s Charles W. Gehrke Proteomics Center comes in.

The Center looks at thousands of proteins with their current technology consisting of six mass spectrometers worth more than $2 million. They serve clients across the UM System and as far away as Mexico and Canada.

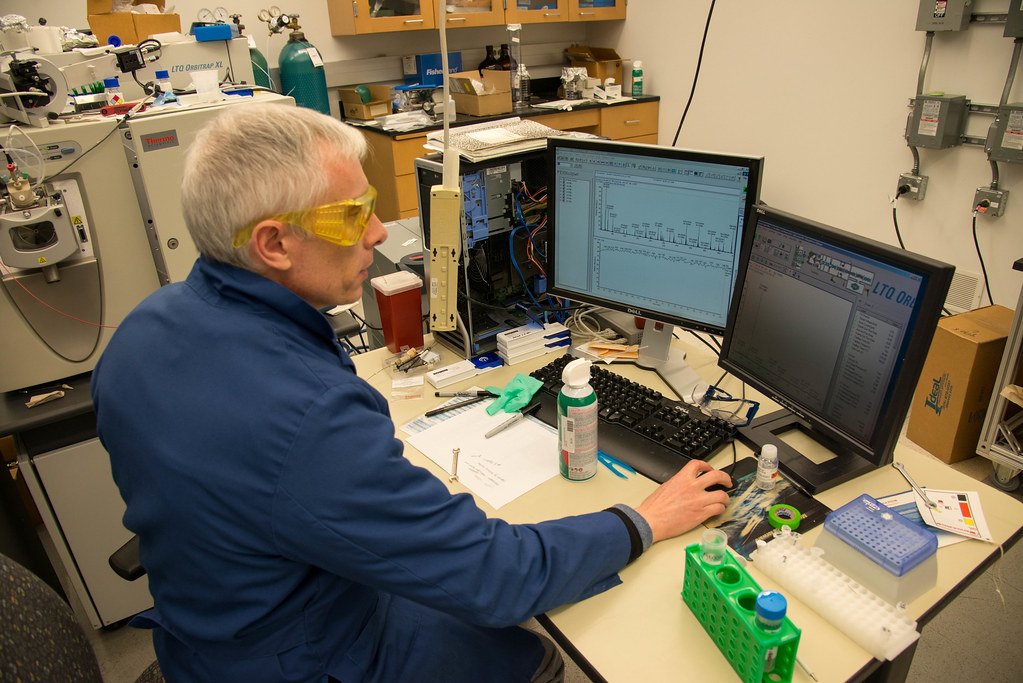

At its core is Brian Mooney, associate director of the center and Roy Lowery, an expert in protein isolation and fractionation and is also learning mass spectrometry.

The Center is often juggling multiple clients each week and sometimes each day. For each new project Mooney sits down with researchers, helps them develop an experimental design, and takes their samples to generate data.

“Sometimes you get to that Eureka moment and you say, ‘I thought this was happening but my hypothesis was wrong and actually this is happening’ and leads to new directions in research. That’s what we’re here to do,” Mooney said.

The center is able to run experiments that look at proteins from a global scale and experiments that target just a small number.

For studies that want to find the difference between a normal cell and a mutant, a global analysis is used to look at all the proteins.

Mooney breaks a cell down and removes everything but its proteins. This fractionation allows researchers to examine a lot more proteins more closely.

“Typically the things that are doing the control in the cell are maybe not as abundant, so you need to dig deeper, so that’s the point of the fractionation,” Mooney explained.

To look even deeper into these, the center can use a technique called SDS-Page to sort the proteins by size.

“We’ve done everything from full plants so leaves and roots, we’ve done it for bacteria cells, we’ve done it for blood, both in humans and in animal models and then we have also done some specific tissues whether it be heart or kidney,” Mooney said explaining the range of this technique.

Recently, the center helped with a project aimed at making better corn hybrids for farmers by finding out which proteins played a role in a process called heterosis.

“We were able to see specific proteins that were involved in processes that suggest this is why you get a taller and healthier hybrid plant,” Mooney said. “One of the major findings was elevated stress-responsive proteins conferring an ability to withstand stress.”

The center also helped researchers at the Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital compare heart tissue between healthy and diseased hearts.

With a targeted approach, the clients already know what proteins they are interested in, so Mooney is able to use equipment to zero in on a much smaller number.

“We are working in a group in biological sciences that are looking at nerve tissue and in this case they are just interested in five proteins and what we’re able to do is ignore everything else and get really good numbers in how much of these five proteins are there,” Mooney explained.

The center is also there to educate. Mooney explained often clients don’t have a clear understanding of proteomics.

This mission of education also occurs for students. Graduate students and post-doctoral students are trained on how to work the instruments and to analyze the results. On the undergraduate level, Mooney presents hands-on lectures and labs to biochemistry classes. The Center also participates in a unique MU-Industry undergraduate internship program (Biochemistry Dept. and EAG, Columbia).

Sometimes the exposure of what the center’s capabilities sparks cross-discipline projects.

In 2015, Mooney worked on a collaborative project with the MU Medical School studying cataract formation in humans.

Last year, Mooney teamed up with biochemists and mechanical and aerospace engineers.

Mooney explained that before the involvement of the Proteomics Center, the researchers were firing a laser at a piece of a protein called a peptide.

“They saw that something weird happened and wanted to know what that weirdness was on the molecular level, so they came here,” Mooney said.

This collaboration led to a publication on how targeting proteins and peptides with a laser can control biological processes in cells and tissues.

MU is not the only university with a Proteomics Center, but having it local comes with a number of advantages. Mooney said subsidies from MU allow the center to offer reduced rates to MU clients. Another advantage is the ability to consistently have someone nearby to talk through their experiment with.

Since 2002, the center has grown from a handful of customers to more than 50 customers a year and a total budget of about $250,000. Direct income from research usually covers about 60-70% of that total, with the remainder being covered by the Office of Research.

Mooney said part of this success and growth is due to an increase interest in proteomics from scientists.

While genes allow researchers to know what might be in the cell and mRNA tells them what is going to be in the cell, the proteins reveal what is currently in the cell.

Many researchers have focused on cells at the DNA and mRNA level, but are now discovering it’s important to consider the protein as well.

Soon a new instrument will be added with funds received through a National Science Foundation MRI grant, one of two awarded to MU in the last 10 years. With the upgraded mass spectrometer, Mooney said, data will be able to be collected faster and better. This advancement will continue to allow the center to do what it does best – proteins.

The MU Proteomics Center is named for Charles W. Gehrke, a former MU professor of Biochemistry. It is one of 10 research core facilities subsidized by MU’s Office of Research to provide services to a range of scientists and researchers across the UM System and the world.