By Sophie Rentschler | Bond LSC

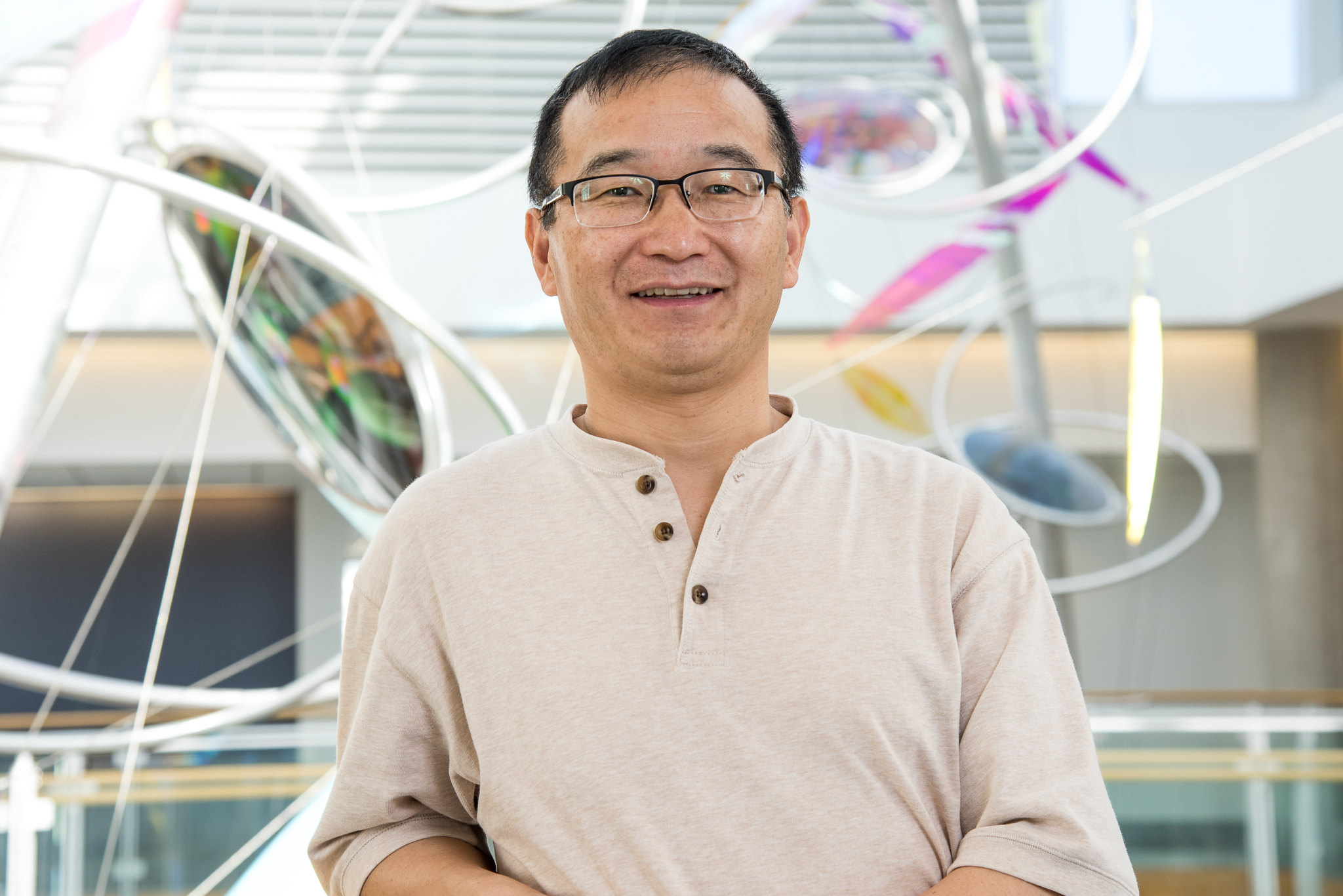

Each day Bond Life Sciences Center’s occupants collectively contribute hundreds of thousands of steps in the pursuit of science.

Faculty, staff and students can be seen hurrying across its bridges that connect east and west wings of the building, and one can get a full picture of the people contributing to the activity within its walls when they emerge en masse during lunch breaks, fire drills or class changes.

Matt Nelson, a senior engineering technician at Bond LSC, is a constant among these. He starts his day at 7:30 a.m. Every morning, he’s one of the maintenance staff that walk through all five floors of the center, checking if any alarms of devices have sounded.

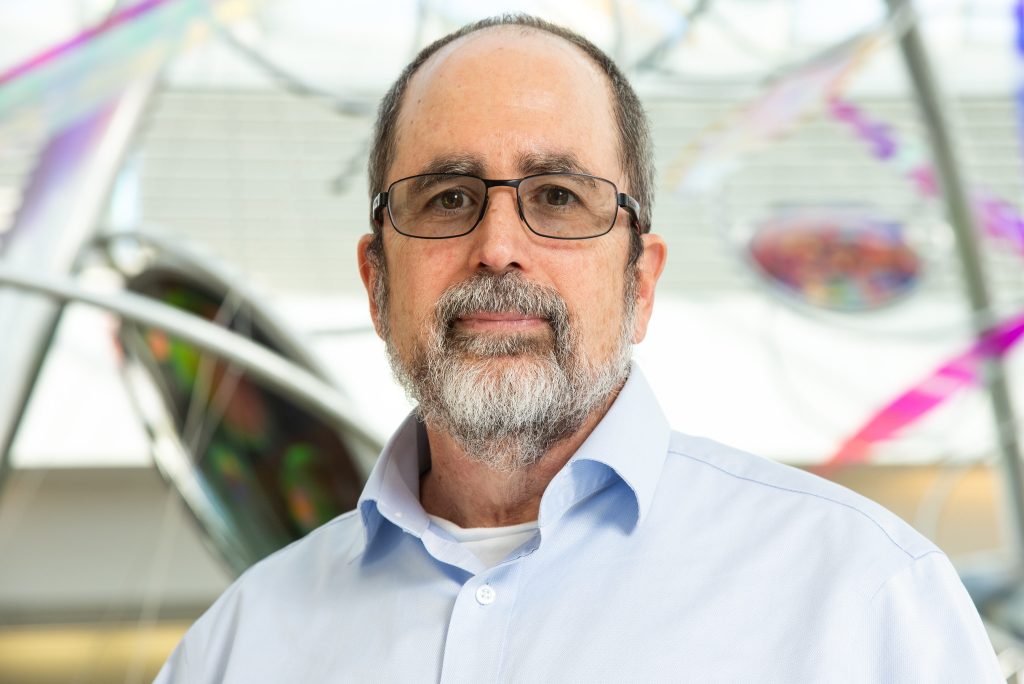

Nelson began at Mizzou as a full-time custodian and student, which he said paved a path to for him to graduate free of student debt. He got into the trades before graduation; working is way up to his role today. Now, he often repairs freezers at Bond LSC, some of the Ultra-Low Temperature Freezers require energy usage equivalent to three households. But, he works on all sorts of equipment.

“Working in this role can sometimes be taxing mentally and physically,” he said. “But there are times when you feel like someone’s hero for fixing something that they were told wasn’t repairable or being able to repair equipment quickly and inexpensively.”

Throughout the day, he ping-pongs from Bond LSC to the service building north of the center, often taking a tunnel connecting the two buildings. It’s a pathway for the travel of machinery, air tanks and people. The tunnel is jokingly referred to by the maintenance crew as the “artery of the building,” and Nelson goes through this tunnel 30 times a day, on average.

Nelson said most of his workdays are unpredictable. “It is fast paced, challenging and somewhat unrelenting,” he added.

He can be spotted running up the stairs to tend to his latest projects. He spends his days managing flooring installation projects, delivering carbon dioxide tanks, ensuring a successful move for principal investigators new to the building and maintaining negative 80-degree freezers and other equipment.

His phone tells him he averages around 15,000 steps a day, roughly five miles.

Nelson said the way he stays energized throughout the day is maintaining a high caloric intake, with lots of fats, protein and carbs as fuel. He added that his true fuel, though, is his drive to do his job: assisting the center with the technical support side of research to save the labs money.

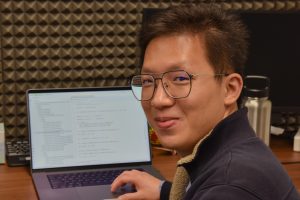

Though Nelson has a designated desk space, he doesn’t use it. His job requires movement; if he were to sit at his desk he would likely be swarmed by questions. Instead, he can be seen squatting around Bond LSC with his computer in his lap, ready to add to his daily steps for science.

“Throughout my workday there is usually no moment of calm,” Nelson said.