Scientists prove parasite mimics key plant peptide to feed off roots

By Roger Meissen | Bond LSC

When it comes to nematodes, unraveling the root of the issue is complicated.

These tiny parasites siphon off the nutrients from the roots of important crops like soybeans, and scientists keep uncovering more about how they accomplish this task.

Research from the lab of Bond LSC’s Melissa Mitchum recently pinpointed a new way nematodes take over root cells.

“In a normal plant, the plant sends different chemical signals to form different types of structures for a plant. One of those structures is the xylem for nutrient flow,” said Mitchum, an associate professor in the Division of Plant Sciences at MU. “Plant researchers discovered a peptide signal for vascular stem cells several years ago, but this is the first time anyone has proven that a nematode is also secreting chemical mimics to keep these stem cells from changing into the plant structures they normally would.”

Stem cells? Xylem? Chemical mimics?

Let’s unpack what’s going on.

First, all plants contain stem cells. These are cells with unbridled potential and are at the growth centers in a plant. Think the tips of shoots and roots. With the right urging, plant stem cells can turn into many different types of cells.

That influence often comes in the form of chemicals. These chemicals are typically made inside the plant and when stem cells are exposed to them at the right time, they turn certain genes either on or off that in turn start a transformation of these cells into more specialized organs.

Want a leaf? Expose a stem cell to a particular combination of chemicals. Need a root? Flood it with a different concoction of peptides. The xylem — the dead cells that pipe water and nutrients up and down the plant — requires a particular type of peptide that connects with just the right receptor to start the process.

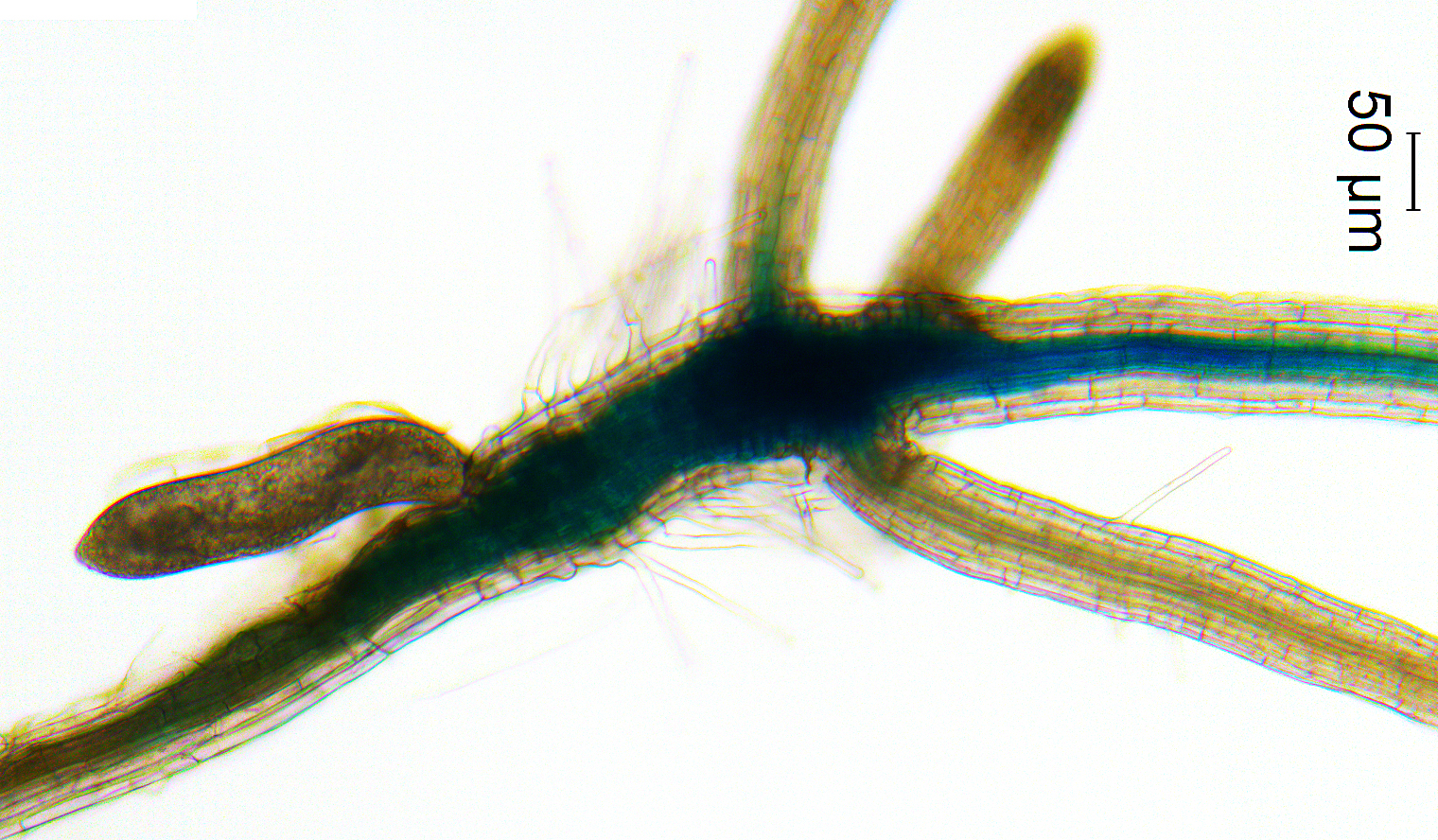

But for a nematode, the plan is to hijack the plant’s plan and make plant cells feed it. This microscopic worm attaches itself to a root and uses a needle-like mouthpiece to inject spit into a single root cell. That spit contains chemical signals of its own engineered to look like plant signals. In this case, these chemicals — B-type CLE peptides — and their purpose are just being discovered by Mitchum’s lab.

“Now a nematode doesn’t want to turn its feeding site into xylem because these are dead cells it can’t use, so they may be tapping into part of the pathway required to maintain the stems cells while suppressing xylem differentiation to form a structure that serves as a nutrient sink,” Mitchum said. “To me that’s really cool.”

This means these cells are free to serve the nematode. Many of their cell walls dissolve to create a large nutrient storage container for the nematode and some create finger-like cell wall ingrowths that increase the take up of food being piped through the roots. For a nematode, that’s a lifetime of meals for it while it sits immobile, just eating.

But how did scientists figure out and test that this nematode’s chemical was the cause?

Using next generation sequencing technologies that were previously unavailable, Michael Gardner, a graduate research assistant, and Jianying Wang, a senior research associate in Mitchum’s lab, compared the pieces of the plant and nematode genome and found nearly identical peptides in both — B-type CLE peptides.

“Everything is faster, more sensitive and we can detect things that had gone undetected through these technological advances that didn’t exist 10 years ago,” Mitchum said.

To test their theory, Xiaoli Guo, postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study in Mitchum’s lab synthesized the B-type CLE nematode peptide and applied it to vascular stem cells of the model plant Arabidopsis. They found that the nematode peptides triggered a growth response in much the same way as the plants own peptides affected development.

They used mutant Arabidopsis plants engineered to not be affected as much by this peptide to confirm their findings.

“We knocked out genes in the plant to turn off this pathway, and that caused the nematode’s feeding cell to be compromised. That’s why you see reduced development of the nematode on the plants.”

This all matters because these tiny nematodes cost U.S. farmers billions every year in lost yields from soybeans, and similar nematodes affect sugar beets, potatoes, corn and other crops.

While this discovery is just a piece of a puzzle, these pieces hopefully will come together to build better crops.

“You have to know what is happening before you can intervene,” Mitchum said. “Now our biggest hurdle is to figure out how to not compromise plant growth while blocking only the nematode’s version of this peptide.”

Mitchum is a Bond LSC investigator and an associate professor of Plant Sciences in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. The study “Identification of cyst nematode B-type CLE peptides and modulation of the vascular stem cell pathway for feeding cell formation” recently was published by the journal PLOS Pathogens in February 2017.