How bossy insects make submissive plants create curious growths

By Samantha Kummerer | Bond LSC

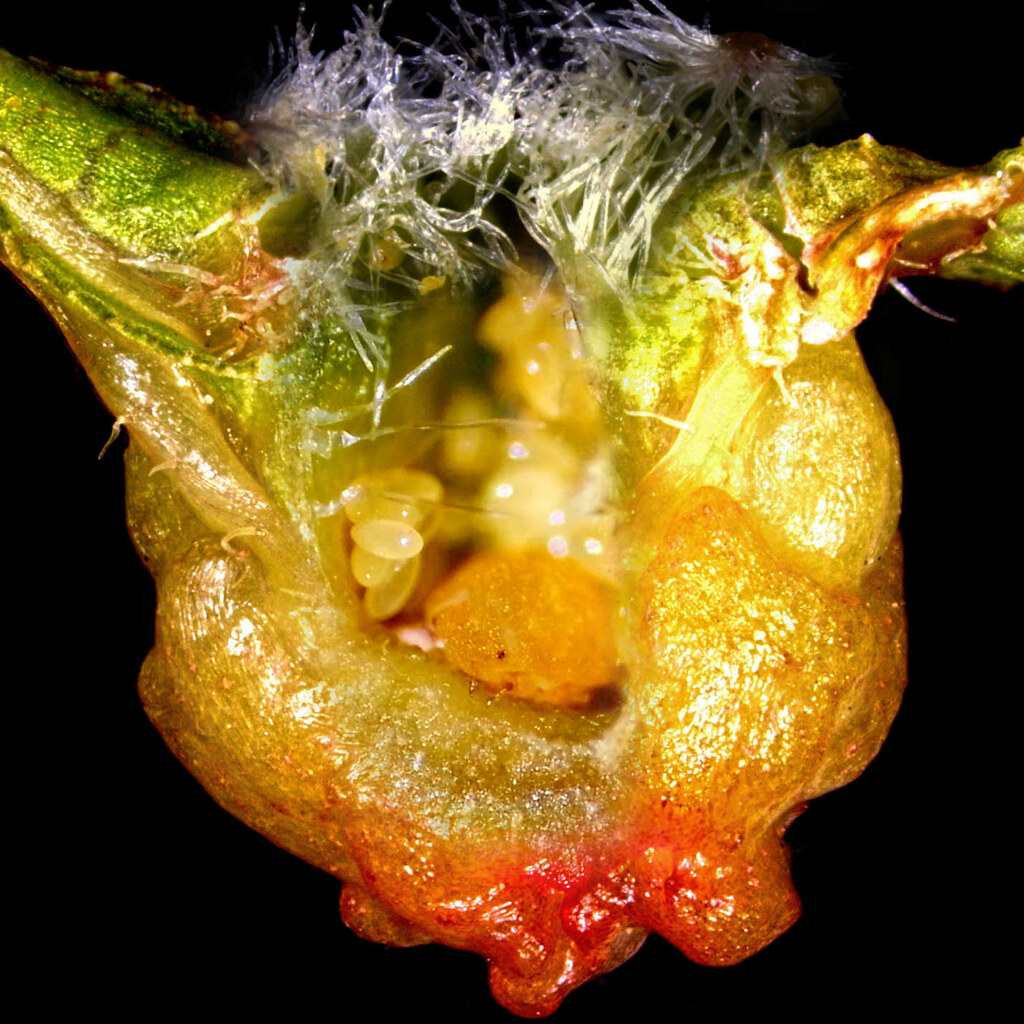

They are bumps on leaves, bulges in stems and almost flower-like growths from plant tissue with a striking amount of variety. They are galls.

These unnatural growths garnered the curiosity of Jack Schulz for years. While he’s spent 40 years studying topics from Insect elicitors to habitat specialization by plants in Amazonian forests, what he’s really wanted to study was galls.

“It’s so weird,” said Schultz, director of the Bond Life Sciences Center. “I’ve always been really curious about how these strange structures form on plants.”

Schultz has spent the last two years trying to answer that question, looking at their development and the underlying genetic changes that make galls possible.

He’s not alone in his fascination.

“I found my very first gall when I was a masters student,” said Melanie Body, a postdoctoral researcher in Schultz’s lab. “I was really excited because it was here the whole time, I just didn’t see it. One of my teachers showed me and it was like a revelation, basically, what I wanted to work on.”

These “strange structures” are often mistaken for fruit or flower buds on a variety of plants from oak trees to grapevines and there’s a good reason why…

“A gall on a plant is actually, at least partly, a flower or a fruit in the wrong place,” Schultz said.

These galls can be the size of a baseball or the size of a small bump depending on the plant. They can also range from just small green bumps on the undersides of leaves to vivid complex growths of color.

Despite the variety, the one thing consist across plants is that the gall is not there by the plant’s choice.

“The insect has a pretty good strategy because it starts feeding on the plant and it will create a kind of huge structure, huge organ, where it can live in, so it’s making it’s own house,” Body said.

The reasoning behind the formation is relatively unknown, however, it is hypothesized that the insect flips a switch within the plant. The insect is not injecting anything new, but rather turning off and on certain genes within the plant.

Schultz explained the galling insect has the power to changes the expression of genes and in some instance disorient the plant’s determination of what is up from down.

The Problem

So how does this affect the plant?

Not only is the insect creating the gall against the plant’s nature, it is also using the plant’s energy and materials for the job.

“I think it’s very cool to imagine an insect can hijack the plant pathway to use it for its own advantage,” Body said.

The insect receives protection and a unique food source and in turn, the plant is left with fewer resources.

“From the plant’s point of view that’s all materials that could have gone into growth and reproduction, so you can think of these galling insects as competing with the plant they’re on for the goodies the plant needs to grow and reproduce,” Schultz explained. “That’s not so good for producing grapes.”

Grapevines are just one of the many plants that galls can form on, but also the plant Schultz’s research uses.

“In our case we work on grapes, so it can be a big issue if the fruits are not sweet enough anymore, because if you don’t have sugar in the fruit then it’s not good enough for the wine production, so it’s pretty important,” Body explained.

In Missouri, the story of grapevines and galls goes back to the 1800’s.

The story goes, the phylloxera insect found its way over to France. Soon it spread throughout the country; wiping out vineyard after vineyard.

“The great wine blight and the world was going to lose all wine production because of this pest,” said Schultz.

Luckily, a small discovery in native Missouri grapevines led to a solution that allowed wine drinkers to rejoice and scientists to puzzle.

“There’s something about the genes in Missouri grapevines that protects them against this insect,” Schultz explained.

While the European wine industry faced extinction, the phylloxera insect, coexisted with native Missouri grapevines. So, now every grapevine in a vineyard is grafted with insect-resistant roots from Missouri grapes.

But, no one really understands what’s so special about grapevine roots in Missouri.

The research

These galls aren’t new. They’ve actually existed for up to 120 million years. But, here’s what is:

“When we started this research, we thought this is a really well-studied insect,” Schultz said. “It turns out there is an awful lot we don’t know about them.”

The team collects samples of galls from grapevines at Les Bourgeois. Back in the lab the galls are dissected using very small tools and then examined with a microscope. Under the microscope, a colony of the insects emerges. The otherwise miniscule mother insect and her 200 eggs can be seen alongside other insects just moving around the gall.

Body compares the insects’ round textured bodies to oranges but with two black eyes.

Schultz’s team hypothesized that there are specific flower or fruit forming genes that are necessary for the insect to create a gall.

To answer this, the team looks at which genes are turned on when the insect creates the formation of a gall. Those observations by themselves don’t prove which genes are essential. So, next, the researchers manipulate the genes by changing the gene’s expression.

“If we find that Gene A is always on when the insect causes a gall to form, we can stop the expression of Gene A to test the hypothesis that it needs gene A to get the gall to form,” Schultz explained. “We can ask a plant. If you lack Gene A, can our insects still form galls?”

The researchers are still analyzing the results, but the current findings suggest that some genes do reduce the insect’s ability to make a gall.

Since beginning the research two years ago, Schultz said he has discovered, “all kinds of crazy things”.

Schultz said it was previously believed that the insect was staying in one place when making the circular gall, but actually, the little insect is moving around; something no one realized before.

And that’s not the only myth this research is debunking. For example, many believe there is one insect per gall, but this turns out to be incorrect. The gall can actually become a hospital of sorts where many mother insects flock to move in and lay their eggs.

And although galls sounds like an odd area of study, the research actually falls under basic developmental biology.

Schultz said research on galls could lead to discoveries about flowering and fruiting.

“Finding a situation in which flower or fruit structures are forming in odd places is actually suggesting to us, pathways and signals that are probably not as well studied in developmental – normal flowers and fruits,” Schultz said.

Beyond curiosity, one of the reasons to study the galls is to find a way to reduce the number of pesticides used on grapevines. The small size of the galling-insect causes grape growers to spray a lot of chemicals.

There’s a lot of discoveries, a lot of implications, but also still a lot of unknowns. Schultz doesn’t let that discourage him.

“If we knew everything about all kinds of things in nature, I’d be out of business and we’d have nothing to do,” Schultz reassured.

The curiosity behind the research continues to hold true for both Schultz and Body outside the lab. From collecting galls for each other to photographing the mysterious spheres, the two are always on the look out for the hidden work of the tiny insect.

“They’re everywhere,” Body said.