By Katelyn Brown | Bond LSC

For researchers, the shape of molecules gives insight into how cells, viruses and other macromolecular interactions take place.

Getting a clear view of that structure is the hard part, and the new Molecular Interactions Core (MIC) at the Bond Life Sciences Center will now give researchers from many different disciplines one place where state-of-the-art equipment are available for them to use to further science.

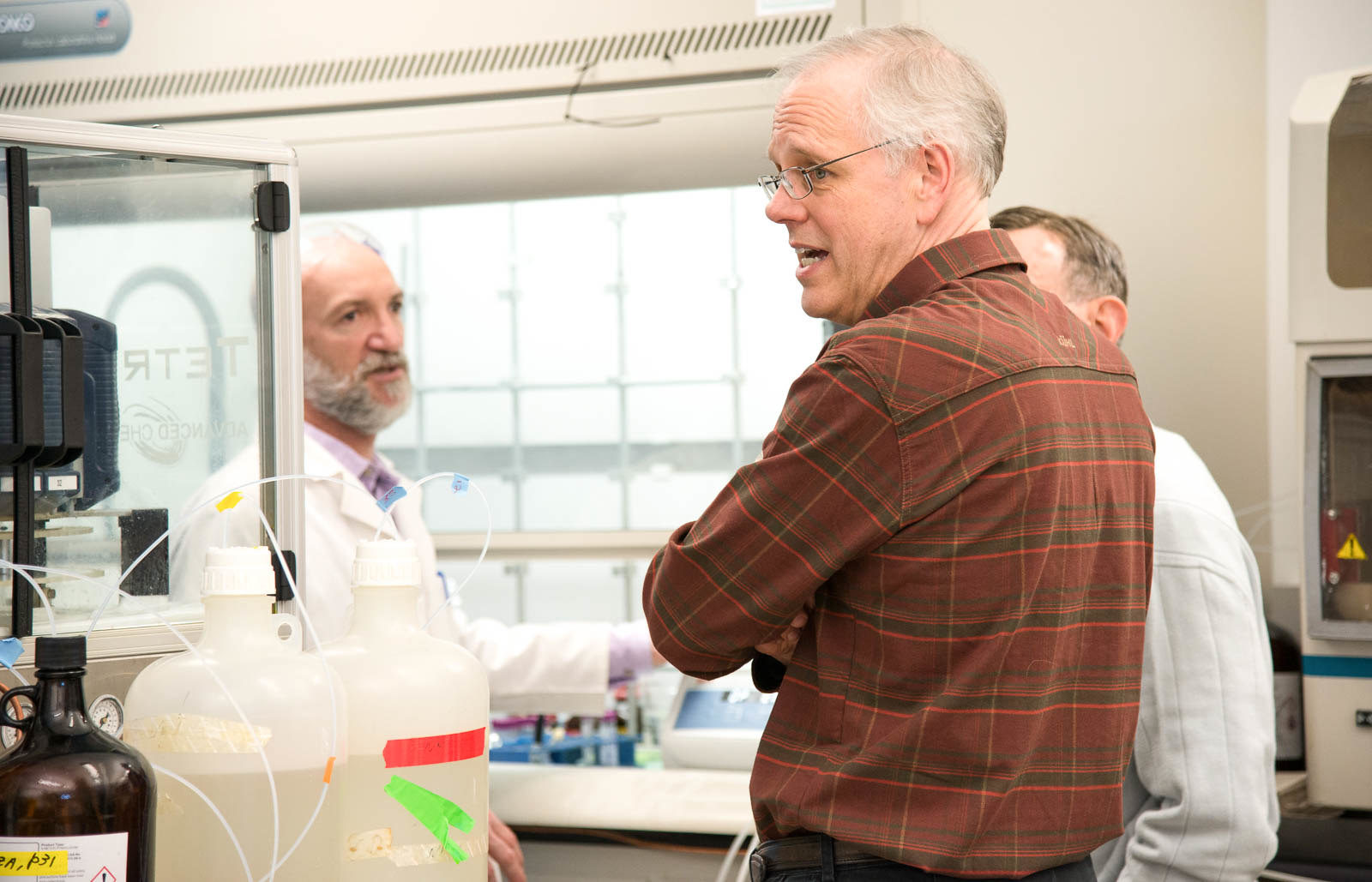

Dr. Kamal Singh is excited that goal is being realized.

One of the 10 MU’s core facilities that serve scientists’ needs, the MIC specifically provides training, advising and shared equipment for researchers to take a closer look at molecules.

That’s where Dr. Singh comes in.

He serves as the Assistant Director of the MIC and oversees the day-to-day operations of the facility. Dr. Singh makes sure the machines are operational, communicates with researchers interested in using the facility, trains those who do not yet know how to use the equipment and gives guidance as well as collaborative feedback on things like computer-assisted drug design — his specialty.

The humming of machines is the first thing noticed when walking into the MIC. These instruments allow you to look at 3-dimensional models of the molecules like HIV enzymes or view protein crystals under a microscope before diffracting light through them. It’s a lab where miniscule pieces of life become big and important.

Dr. Mark McIntosh, the vice chancellor of research for all UM system campuses, had the idea to create the MIC.

“It was Dr. McIntosh’s vision to bring everything together; which includes structural biology, molecular interactions, particle size, zeta potential, mass of the nanoparticles, etc. He also wanted to bring peptide synthesis here to have everything at one central location,” Dr. Singh said.

Understanding structure at the molecular level helps scientists figure out how reactions happen, how molecules fit together and serve as signals and how pathogens can invade cells, among other possibilities.

“I’m hoping that we can really facilitate structural and molecular research on campus — structural determination and molecular interactions — and really push boundaries of the current state of the field,” said Dr. Tom Quinn, the Director of the MIC.

Dr. Quinn hopes the state-of-the-art equipment will allow the MIC to be a resource for both research faculty and students to be on the cutting edge in their fields.

Dr. Ritcha Mehra-Chaudhary and Dr. Fabio Gallazzi work within the MIC and provide their expertise. Dr. Mehra-Chaudhary works with X-ray crystallography, dynamic light scattering and custom protein expression, while Dr. Gallazzi is an expert in custom peptide synthesis. Their work can be important for understanding drug design to combat viruses and cancers.

The MIC started with one machine, an X-Ray Diffractometer, in room 442 of the BLSC. It took six months to collect the different machines from different departments in the campus, but in December the MIC became fully operational. The MIC team celebrated with an open house on Jan. 24, 2018.

“It’s kind of crowded, but it’s good,” Dr. Singh said. “We have invited everyone, mainly researchers, but also undergrads. The entire university is welcome to come see what we have. The idea is the advancement of science in our school.”

The MIC won’t only be beneficial for campus researchers, but also researchers from all over and undergrad students who are eager to learn the details of molecular interactions and learn how to use core facilities.

There are many exciting and new technologies in the MIC that will interest outside researchers, according to Dr. Quinn. One of these is the nanodisc technology that Dr. Mehra-Chaudhary works with. This technology allows researchers to study membrane proteins outside of something bigger, like a cell, while also keeping them in a functional and native structural state. The nanodisc project is part of collaboration between the MIC and the Electron Microscopy Core to allow researchers to get high resolution structures of membrane proteins.

While affordable, outside and campus researchers must also pay a price to use the facilities to cover consumables, instrumentation maintenance and staff.

“We definitely want to at least break even. I don’t know how long it will take to get there. However, the major goal is to support the scientists on campus and facilitate their research,” Dr. Singh said.

Bringing this support to campus also means supporting future scientists. Dr. Singh has three undergraduate students working with him who are learning how to use the advanced technology, and he helps to train many more from all different departments.

The goal is to one day expand the MIC to a point where all molecular interactions facilities can be at one place.

“There are certain techniques we don’t have, and I hope that in the future we will get them. We hope to provide all modern techniques to the university community in coming years. Not only linked to that room, we want to expand it,” Dr. Singh said.

Dr. Quinn agrees, and he hopes that as researchers come and use the core. In the process the core can understand future needs and where the research is moving to see what new technology under their umbrella could be added to keep supporting the scientists.

The MIC is a big step for the MU research community, and staff is hopeful that it will continue to grow and produce life-altering research.