By Cara Penquite | Bond LSC

When Samantha Yanders stepped to the front of Monsanto Auditorium, she followed presentations from two researchers with three degrees each.

Yanders only had three years of undergraduate research experience.

Nevertheless, she pinned the microphone to her tie, ran her fingers through her short curly hair, and explained her research with a calm certainty to her voice.

Having just finished her junior year as a plant science undergraduate, Yanders spent the first week of her summer sharing her passion for plants with fellow researchers during the 2022 Interdisciplinary Plant Group Symposium.

“I want to be inclusive in how I talk about my work to be able to educate people,” Yanders said. “Even if you’re talking to molecular biologists, they may have no idea about extracellular ATP.”

A clear communicator and advanced undergraduate researcher, Yanders was selected to present her research in Monsanto Auditorium during the symposium and often helps write and edit manuscripts for her lab.

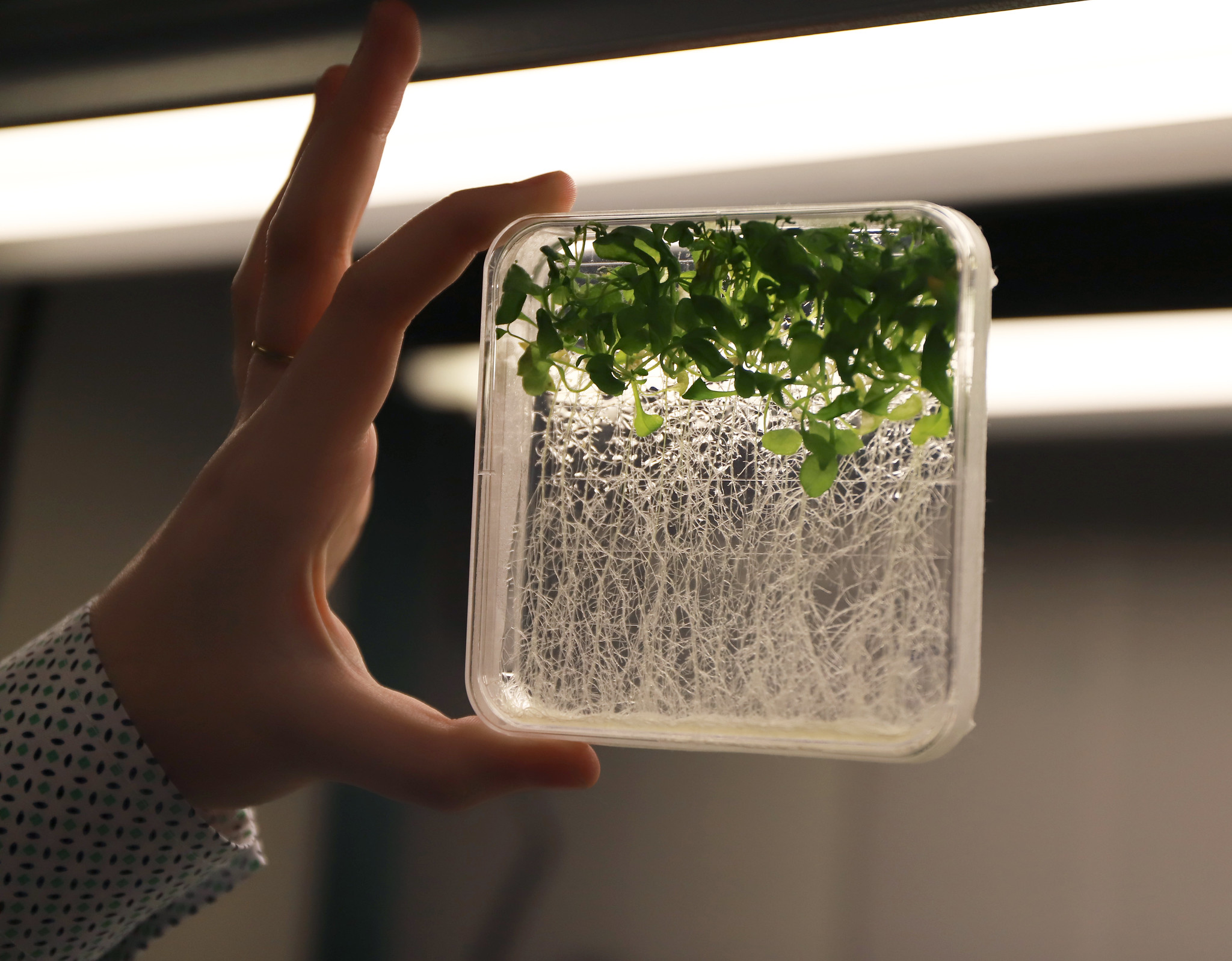

Yanders began research in the Gary Stacey lab through Freshman Research in Plant Science, a program that places plant science freshmen in MU labs. Yanders’ research focuses on the signaling role of extracellular ATP when a plant experiences high-salt conditions.

Within a cell, ATP is a molecule used for energy. However, research shows that when a plant is in high stress or damaging conditions, ATP outside the cell signals for protective mechanisms.

“It’s really clever because instead of spending energy to make both a signaling molecule and a signal receptor, it already has something that’s really high concentrations in the cell and very low concentrations outside the cell,” Yanders said. “So it’s easy for the plant. It just has to make a signal receptor.”

Under normal conditions there is less ATP outside the cell and a high concentration of ATP inside the cell since it is used as energy. However, under high salt conditions there is an increase in ATP outside the cell, which binds to receptors on the cell surface that communicate with the cell to stunt plant growth. Yanders’ work explores the impact of high salt environments for plants — an increasingly relevant project as climate change raises sea levels and increases salt deposits in soil.

Although she now enthusiastically recounts her work to auditoriums of fellow scientists, biology was not originally Yanders’ first choice.

“In high school, I knew that I wanted to do something scientific because I’ve always liked science,” Yanders said, “But I didn’t think I wanted to go into biology, because I saw biology as mainly oriented towards animals.”

With her geneticist grandfather piquing her interest from a young age and her enthusiasm for environmental science in high school, once she learned Mizzou had a plant science program she was ready to commit.

“So I was like, ‘Okay, I’ll go into biology and focus on plants.’ And then I’m looking on the Mizzou website and they [have] plant science. I didn’t even know that was a thing,” Yanders said. “So I switched to plant science.”

After enjoying high school chemistry labs, Yanders was ready to take the next step into research labs as soon as possible. Freshman Research in Plant Science allowed Yanders the opportunity to join a lab right away — fostering her interest in plant research.

“As humans, we move around. We can adapt to change by moving and changing what we do,” Yanders said. “But a plant has to do all of that management from a stationary position. . . It can’t change the circumstances that it’s in, so it has to adjust itself to be able to adapt.”

Yanders’ love of plants extends beyond the walls of the lab, and she spends her free time in her herb garden where she learns more about plant and human interactions.

“The way that you interact with the plant fundamentally changes how the plant acts,” Yanders said. “So like with basil, if you just let a basil plant grow it just gets leggy and crazy, but if you do what you feel like is harming it by pinching the tops off, then it grows more compact and bushy, which is good for the plant.”

Yanders hopes to explore plant and human interactions in the future, potentially pursuing urban agriculture and ecology.

“I’m really interested in soil health, I feel like we’ve done a lot to deplete soils, and coming up with more renewable ways of doing things [and] producing things for human consumption,” Yanders said.

While uncertain which questions she will ask next, Yanders hopes to continue answering questions and explaining her research to others.

“[I like] being able to offer an explanation, and not just see it, but to create that explanation for other people,” Yanders said.