By Cara Penquite | Bond LSC

Cynthia Tang’s academic career is marked by her propensity to multitask. From earning a major and three minors during her undergrad to making a documentary while getting lab and clinical experience, she makes the most of her time.

Recently Tang received the Excellence in Public Health Award from the United States Public Health Service, and a $181.734 National Institutes of Health grant to be used over four years . . . all while getting an M.D. and Ph.D. simultaneously.

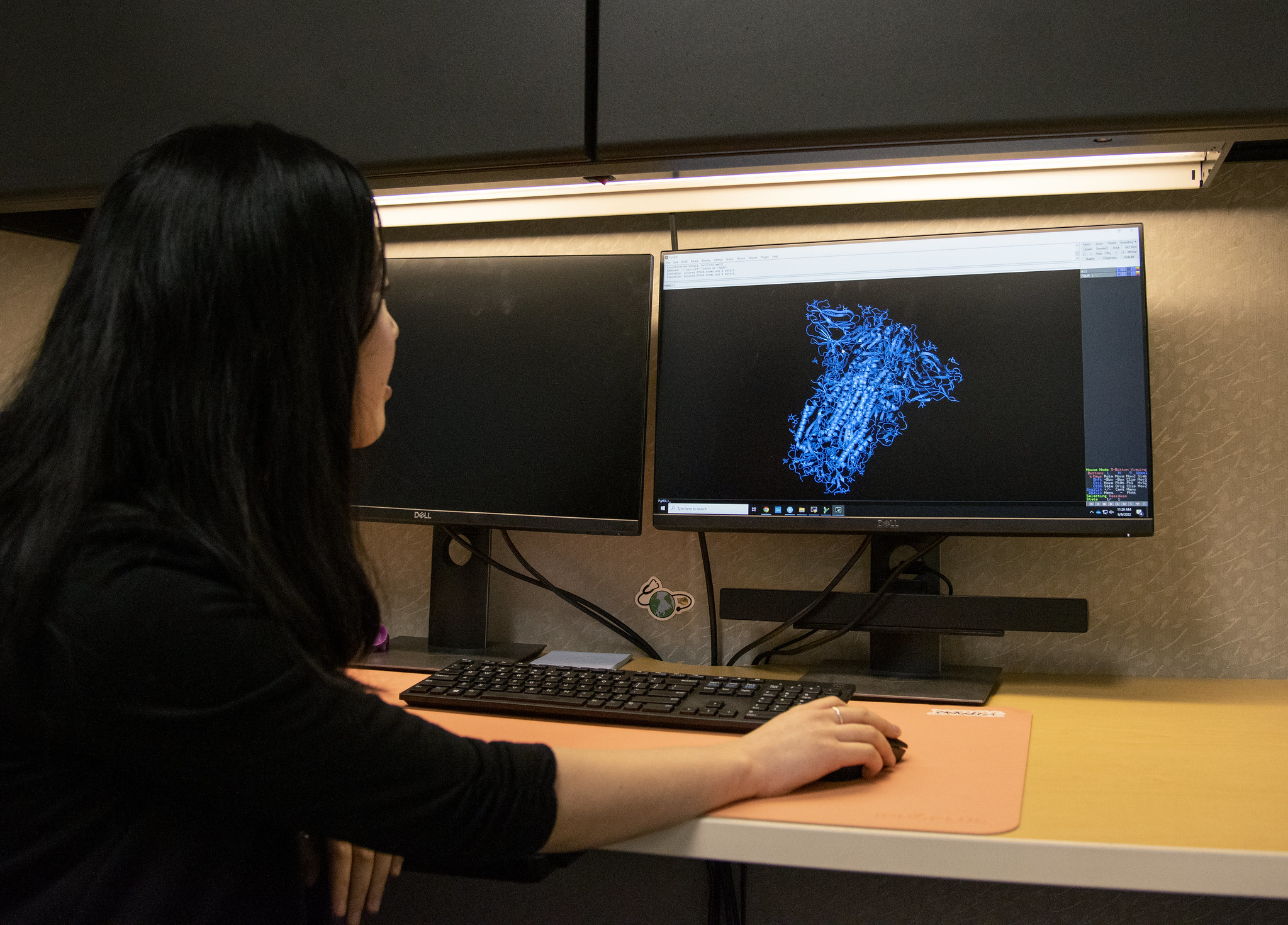

The funding from the grant goes towards Tang’s research on SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, and its effect in rural areas. By comparing DNA sequences of the virus from patients in rural and urban areas, Tang looks for differences in variants. Her goal is to understand how the virus has been evolving and why patients in rural areas experience more severe symptoms.

“I’ve always found infectious diseases really interesting,” Tang said. “This pandemic came up and it was exciting to be in the position to help contribute to the knowledge base of it.”

In a family of immigrants, Tang saw the challenges in health literacy and cultural differences affecting patient care in the U.S first-hand, and she also caught a glimpse into a global view of healthcare.

“I had an opportunity to travel to Vietnam and actually see some of the health disparities of different health care structures in different countries,” Tang said. “We were visiting my grandfather who was in the hospital, and it was alarming to see the contrast between the quality of health care and availability of health care there compared to some of the hospitals that we have here.”

Tang recalls noticing lack of supplies, physicians and space for patients. She saw similar issues in the U.S., and shined light on public health disparities here by creating a documentary about the challenges immigrants face in the U.S. healthcare system. She also held competitions across Washington University’s campus to teach students more about public health issues while working as a clinical research coordinator.

“I wanted to help improve health equity,” Tang said.

A bachelor’s in chemistry and minors in philosophy, international development and pre-health professions at the College of Idaho may start to explain Tang’s public health focus and her path to bench and clinical research.

“My minor in international development was really useful for me because that gave me a lot more exposure to the different economies of different countries of the world, their health status and how politics, economics and health care all interrelate in different countries,” she said.

Her research at Washington University led Tang to an interest in its clinical applications.

“I really enjoyed the aspect of working with patients, actually getting to talk to patients and hearing their stories,” Tang said. “I felt like with clinical research, you can see … slightly quicker results from bench to bedside compared to bench research, and that was also when I decided I was interested in becoming a physician.”

Part of an eight-year joint M.D.-Ph.D. program at Mizzou, Tang started with two years of pre-clinical medical school before transitioning to Ph.D. research and then will return to finish the clinical years of medical training.

When she came to Mizzou, Tang continued fighting health disparities for immigrants.

“We organized a group of volunteers that were able to translate COVID-19 information to different non-English speaking communities in Boone County,” Tang said.

Always one to tackle several projects at once, Tang plans to pursue a career as a pediatric physician scientist interfacing with patients while continuing lab research.

“I like the idea of doing both. As a physician, you get that one-on-one contact and you get to make a very direct contribution to someone’s life,” Tang said. “And then with research, you don’t have as much contact with patients, but what you do can affect populations.”