By Beni Adelstein

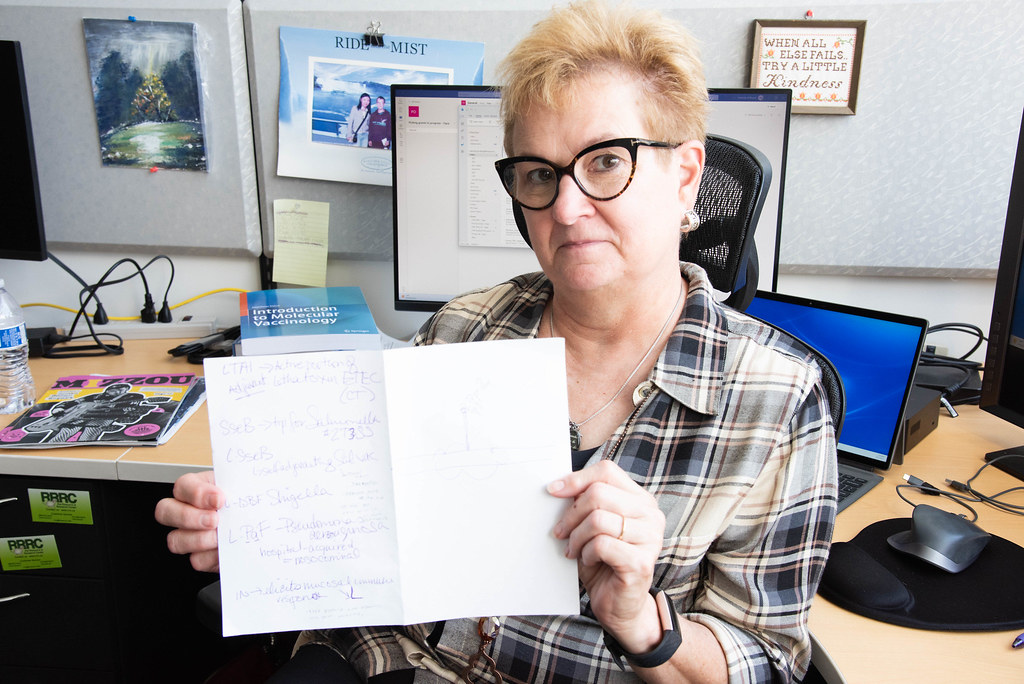

Wendy Picking uses the power of proteins to fight pesky pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Picking and her team are one step closer to completing their mission to develop weapons like vaccines to fight against this bacterium. In March, they published these findings in Nature’s Journal, npj Vaccines.

“If your immune system is weakened and you get Pseudomonas in the hospital, you’re probably going to die,” said Picking, a principal investigator at Bond Life Sciences Center and professor of Veterinary Pathobiology. “We’re doing the basic research, so one day we can make a vaccine to prevent Pseudomonas, so you don’t die in the ER.”

Wendy has spent years developing vaccines against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacteria like Shigella flexneri with husband, Bill Picking, who focuses on the inner workings of the bacteria.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes pneumonia — a lung infection — while Shigella species causes diarrhea. Neither of these are any fun. These and other bacterial infections grow increasingly resistant to drug treatment in hospitals and beyond, so scientists need new ways to combat these pathogens.

A vaccine prepares the body to fight those bothersome bacteria.

By introducing a protein called an antigen into the body, it mimics an infection to trigger a defensive response. It’s like that antigen is a mug shot, so the body’s immune system recognizes what it’s up against and builds antibodies — a weapon tailor-made to fight it. The next time that pathogen tries to infect, the body will have had a way to fight it off.

For Wendy, making proteins that exist in the bacteria work toward this purpose is key.

In 2020, she earned her claim to fame — the discovery that fusing proteins together from the tip of the bacteria’s needle-like syringe amplifies an immune response to a vaccine to help fight off infection. Her lab was the first to discover this method works for these specific pathogens of Pseudomonas and Shigella.

“Producing proteins is expensive so we fuse the two tips to create a self-adjuvating protein, which combines two proteins to trigger and amplify a response,” Picking said.

When she says self-adjuvating, Wendy just means they created a new molecule that both stimulates the immune system and enhances that immune response. It’s like a go signal attaches itself to the vaccine’s proteins. The go signal tells the body to be more aggressive with fighting off those pathogens. Ideally, this will help fight off nasty symptoms of pneumonia or diarrhea.

These fused proteins originally helped the bacteria infect humans. They sit on the tip of a needle-like structure called a type 3 secretion system, which injects specialized proteins into cells to avoid being detected and attacked.

Wendy notes that developing the right animal models is one important part of creating a new vaccine. She has used mice for the Pseudomonas vaccine and rabbits for the Shigella vaccine.

“What you’re trying to do is mimic a human disease in a non-human model system, and you have to be sure that you’re stimulating the immune response in the right way,” she said.

Researchers observe how vaccines affect the immune systems of those animals and apply that knowledge to humans.

In their experiments, mice treated with these fused proteins survived being infected with Pseudomonas unlike the mice that received the placebo.

Now, Wendy’s team continues research on Pseudomonas and is shifting to research a Shigella vaccine. They will continue to test out the protein fusion method, refining vaccine candidates to fight off even more pesky pathogens.

Her most valuable findings are not limited to the experiments, and she said the most rewarding part of her work is seeing former students be successful.

“The most important lesson is picking your staff. Counting on your team, getting along with each other and working together is crucial,” she said. “I can now crash and burn; if these kids we work with are successful, then we’ve left the legacy that we wanted.”

“I want these vaccines to go to market, but we may be retired or dead when that happens.”

Wendy is looking forward to seeing what her group can come up with now.

New technologies like transcriptomics, RNA sequencing, and bioinformatics — available through MU’s research Core facilities in Bond LSC — will help them move their vaccine work forward to achieve this mission. Those pesky pathogens don’t stand a chance.

Wendy Picking’s most recent publication is “A protein subunit vaccine elicits a balanced immune response that protects against Pseudomonas pulmonary infection.” It appeared in the journal npj Vaccines in March 2023.