The safety behind studying deadly disease

By Phillip Sitter | MU Bond Life Sciences Center

You’ve seen it before in the movies.

Sweaty scientists put on their full-body, spacesuit-like get-ups to stave off a potentially extinction-level outbreak and at least one scientist invariably gets infected with the deadly agent of disease.

While popular culture propagates this sense of peril, in reality bio-containment labs are designed with safety in mind.

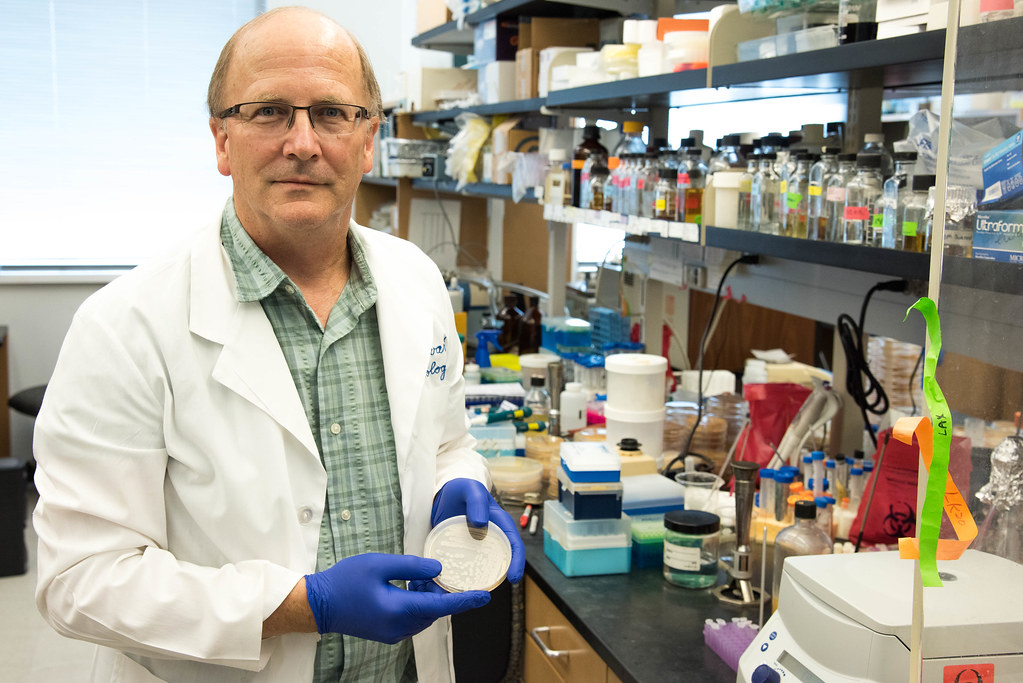

“People tend to think bio-containment facilities are dangerous, mostly from movies I think, but the history is actually spectacular,” said George Stewart, a medical bacteriologist, a Bond Life Sciences Center scientist, McKee Professor of Microbial Pathogenesis and Chair of Veterinary Pathobiology.

For Stewart — whose lab works on the basic science behind anthrax — no one is “under the gun because of big outbreaks, not with the pressure you see in movies.”

But one type of pressure is an important part of bio-containment lab safety. Air pressure differences maintain certain labs at lower pressure compared to the rooms and hallways around them, ensuring that air will only flow in toward a lab and not out, keeping any airborne pathogens trapped inside.

“They know if everything is done properly, it’s perfectly safe for them and even safer for everyone else [outside a lab],” Stewart said of the safety features, procedures and systems of bio-containment lab safety in place at facilities like those at the Bond LSC and elsewhere at MU.

Stewart said he is vaccinated against anthrax. “Whether I have protective immunity or not, I don’t know.”

“Almost like you were working underwater”

The powerful capabilities of anthrax and other lethal pathogens call for particular safety precautions for scientists.

Stewart looks like he’s straight out of the movie Contagion when donning the full-body suit for his more dangerous research in a Bio-Safety Level (BSL) 3 facility at MU’s Laboratory for Infectious Disease Research (LIDR). In the trees on the eastern fringes of campus, the specialized building is where he and other researchers study diseases animals can transmit to humans, including plague, Brucella, tularemia and Q fever, and mosquito-borne diseases like dengue, chikungunya and now Zika virus. The safety protocols and systems at a BSL-3 lab like the LIDR facility Stewart described reflect the likely transmission by aerosols of the human pathogens inside.

After passing through security access to the building and the labs inside, Stewart enters an ante room off of a hallway. The air pressure in this room and the lab beyond it is such that air will only flow in toward the lab, and not out and away.

Anything that goes into the lab only leaves if it is autoclaved, disinfected in a steel machine using pressurized steam that “essentially kills everything, even heat-resistant spores,” so that means Stewart changes clothes, removes his watch, phone and any other personal items.

Next come layered scrubs and a water-proof Tyvek suit with booties and a hood that cover everything but his hands and face. Two layers of gloves take care of his hands, but shielding his face is a bit more technical.

A plastic face cover with a Tyvek hood shrouds over Stewart’s shoulders. Inside, a pump fills the hood with positively-pressured filtered air – this has the inverse effect of the negative pressure of the rooms and keeps air flowing out away from his face and not toward it.

Everything inside the lab and the building is about redundancies like that. A final safety measure is that all work on pathogens take place in bio-safety hoods – HEPA-filtered cabinets.

Stewart said it can be difficult to hear with the air filter systems blowing, so every move by researchers is calculated and announced. Colleagues take their time in handing off equipment to one another, so as to avoid torn gloves.

It’s “almost like you were working underwater as two divers,” Stewart said about working in the BSL-3 lab with a colleague.

“Everything is orchestrated in a very intentional way.”

Only dangerous when dry

Anthrax isn’t always lethal, so the scene is quite different inside a BSL-2 lab at Bond LSC where Stewart studies non-virulent strains.

BSL-2 labs study infectious agents that can cause disease in humans, but are usually treatable. Researchers only need lab coats, gloves and eye protection in these labs and all waste must be autoclaved. Here anthrax and other colonies of organisms are stacked in covered Petri dishes and handled without any Tyvek or air pumps.

The Anthrax bacterium researched here is missing a specific plasmid, a DNA molecule essential for virulence that protects the anthrax bacteria from white blood cells that attack them.

On top of that, all samples in this lab are wet, and anthrax spores are only dangerous as aerosols when dry. Before 2001, Stewart said virulent strains of anthrax were only labeled BSL-2 agents for this reason.

The anthrax letter attacks that year not only changed some of the organism’s lab classifications, but also interest in it. Prior to 2001, Stewart said there was not a lot of funding available for anthrax-focused researchers, a small and tight-knit community. Even though the attacks did spur an increased investment of government money into the field at the time for defense against anthrax as a bio-weapon agent, almost 15 years later Stewart said that funding is more or less back at pre-2001 levels, “perhaps marginally better.”

There are now only a handful of anthrax-dedicated labs in the U.S., Stewart said, trying to name them off as he counted his fingers. The Bond LSC has not had any lab higher than a BSL-2 plus for years now, not since the BSL-3 research moved to LIDR, Stewart said.

Several local residents called when LIDR was under construction and asked questions and voiced concerns about the facility and the work to be done there, Stewart recalled. However, Stewart said he and his colleagues gave the callers honest answers, and he has not heard of any pushback since.

Stewart sees bio-containment labs as positive technological achievements in the study of disease – without them, many advances in treatment would never have been possible. In terms of the work done at facilities at MU and in the Bond LSC, Stewart said “we have the facilities, we have the equipment, we have the training,” to ensure the safety of researchers inside the labs, and even more so everyone else on the outside.

Anthrax is not contagious and responds well to antibiotics, despite concerns in the scientific community Stewart shared that there is a possibility antibiotic resistance could be intentionally engineered into anthrax.

Stewart could only think of a couple of cases when lab workers got infected with the organism through mishaps, and those were at USAMRIID – the United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Disease at Fort Detrick, Maryland – when anthrax was produced there in very large quantities for research of it as a bio-weapon during the Cold War.

When you spend a lot of your time working with potentially lethal pathogens though, what do you tell your doctor when you come in with flu-like symptoms? Stewart said that not only does he and any of his colleagues disclose to their doctor the organisms that they work with, but doctors at MU already know exactly what organisms are being researched inside the LIDR labs. As a precautionary measure for their own well-being in case accidental infection did occur in a lab after all, Stewart or another colleague working with anthrax who turned up sick would receive antibiotics just to be safe – “there are standard operating procedures for everything.”

He does not want to make light of the dangerous organisms he works with, but inside the BSL-3 facility at LIDR, Stewart said that breathing in HEPA-filtered air all day there does do wonders for his hay fever.

Stewart couldn’t help but share a chuckle with that one. Laughter might be the most un-containable thing in nature.