By Mariah Cox

How did an undergraduate student from Truman State University spend last summer working on a research project with a Bond Life Sciences Center primary investigator and become on track to be published as first author several months thereafter?

A nationwide National Science Foundation (NSF) sponsored program has allowed Mary Butler to jump-start her research career early on.

Butler, a sophomore biochemistry and molecular biology student, wanted to get a head start on research to give her a leg up and figure out what her future might look like. As a freshman, Butler joined the Missouri Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (MOLSAMP) program and sought out opportunities that aligned with her science interests.

MOLSAMP is a collaborative effort among seven public universities, a private university and a community college. The alliance aims to increase the number of underrepresented minority students throughout the state of Missouri who pursue undergraduate degrees in science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM). The Missouri chapter is part of a greater program with the Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation sponsored by the NSF, and Butler qualified because of her Mexican American background.

This past summer, Butler started traveling the 90 miles from Kirksville to Columbia to work with Cheryl Rosenfeld, a primary investigator at Bond LSC. Her research primarily focused on how genistein, a soy-derived phytoestrogen, and BPA, an industrial chemical, affects the behavior of mice.

“BPA and genistein are endocrine-disrupting chemicals, so they can mess with the hormones of an animal and potentially humans. I specifically looked at the different behaviors of California mice under four different diets,” Butler said.

The researchers administered a control, a genistein diet, a low dose BPA and a higher dose BPA diet to pregnant mice. After the baby mice were born, the researchers weened them from the mother to observe if the parents’ diet affected what the pups ate. Additionally, at 30 days, 90 days and 180 days, they put the pups through various social tests to see if their diet and their parents’ diet affected the brain and behavioral patterns.

They used socio-communication testing to determine whether developmental exposure to these chemicals led to deficits in these behaviors, which are reminiscent of those seen in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The results point to less socialization among the mice exposed during the pre- and postnatal period to genistein or a low dosage of BPA.

Afterward, Butler measured gene expression changes in the hippocampus, which regulates learning and memory, and the hypothalamus, which guides socio-sexual behaviors. Besides examining for mRNA that encodes for proteins that can act within or outside of a cell, Butler and Rosenfeld also are the first group to examine whether developmental exposure to BPA and genistein affects the expression of so-called junk RNA within the brain.

Junk RNA strands are very short and do not give rise to proteins. For these reasons, they were historically dismissed as not important in cellular biology. However, it is increasingly apparent these RNA strands, also now called microRNA or miR for short, play vital roles in diverse cells throughout the body.

One way they act is to bind mRNA that would otherwise encode for proteins. In so doing, they help contribute to the demise of these mRNA strands. Essentially, the DNA can be transcribed to mRNA but miR binding prevents them from making a protein, acting as an epigenetic modifier that doesn’t alter the DNA or mRNA. In this sense, miR may serve as a system to help regulate mRNA.

While other research groups have examined how BPA affects miR patterns in the placenta and testes, no previous research group has done so in the brain, even though this organ is vulnerable to early exposure to BPA and genistein.

When Butler started in the Rosenfeld lab, she expressed a desire for challenging and novel work. With assistance from Jiude Mao in the Rosenfeld lab, they set out to test whether developmental exposure to BPA and genistein could alter miR decrease in ASD patients.

Notably, Butler’s work suggests that indeed such chemicals caused down-regulation of the same miR that are reduced in ASD patients. Normal expression of such miR appears to help prevent cell death, oxidative-stress damage, and yield other beneficial effects, and thus, reductions in these miR may leave California mice and, presumably, autism patients more vulnerable to such deleterious effects exposed to such chemicals.

Butler’s studies also suggest that changes in mRNA and miR profiles are associated with socialization deficiencies observed in California mice. Further testing is needed to confirm whether these molecular changes contribute to these behavioral disruptions, but, if so, it may pave way for new prevention and treatment strategies in those at risk of neurobehavioral disorders.

Since high school, Butler knew she wanted to pursue science. But she doesn’t quite know where to go from here with all the different options available; the opportunity at Bond LSC allowed her to look into one of those.

“I want to explore a lot of different types of research. My research with Dr. Rosenfeld is very different than the research I’ve been doing at Truman,” said Butler. “I had been looking at Dr. Rosenfeld’s research for a while and it looked really cool, so I sent her an email and asked if I could work in her lab over the summer. She said ‘yeah’ quickly, and it was really exciting.”

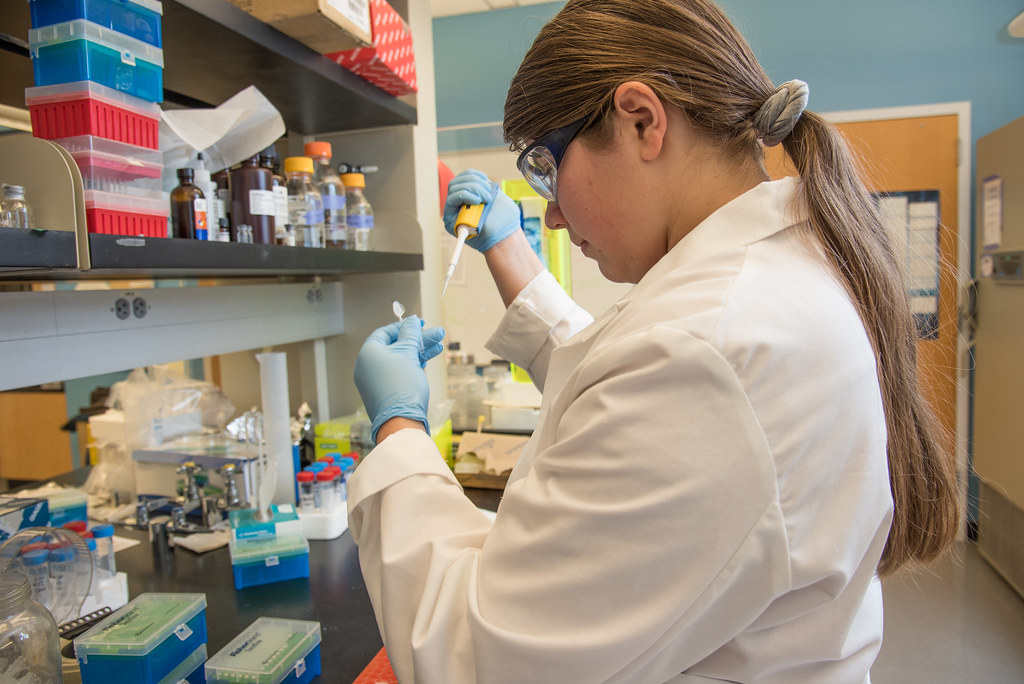

As a sophomore, Butler can say she’s the first author on a paper, and she knows how to do protein expression purification and polymerase chain reaction among other techniques.

“I really enjoy it because I’m more of a hands-on learner. Getting to do it hands-on, I’m able to absorb a lot more information,” Butler said. “In my classes, I’m able to follow along and talk about research things because I already know a lot of the techniques we discuss and practice in the lab.”

Butler’s research was published in the “Journal of Neuroendocrinology” in March 2020 and was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.