Ever wonder why scientists love science? We asked. Happy Valentine’s Day.

February 2015

Harm and response

We often think of damage on a surface level.

But for plants, much of the important response to an insect bite takes place out of sight. Over minutes and hours, particular plant genes are turned on and off to fight back, translating into changes in its defenses.

In one of the broadest studies of its kind, scientists at the University of Missouri Bond Life Sciences Center recently looked at all plant genes and their response to the enemy.

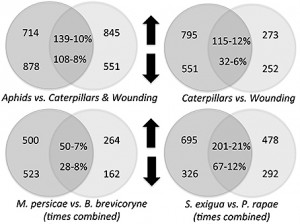

“There are 28,000 genes in the plant, and we detected 2,778 genes responding, depending on the type of insect,” said Jack Schultz, Bond LSC director and study co-author. “Imagine you only look at a few of these genes, you get a very limited picture and possibly one that doesn’t represent what’s going on at all. This is by far the most comprehensive study of its type, allowing scientists to draw conclusions and get it right.”

Their results showed that the model Arabidopsis plant recognizes and responds differently to four insect species. The insects cause changes on a transcriptional level, triggering proteins that switch on and off plant genes to help defend against more attacks.

The difference in the insect

“It was no surprise that the plant responded differently to having its leaves chewed by a caterpillar or pierced by an aphid’s needle-like mouthparts,” said Heidi Appel, Bond LSC Investigator and lead author of the study. “But we were amazed that the plant responded so differently to insects that feed in the same way.”

Plants fed on by caterpillars – cabbage butterfly and beet armyworms – shared less than a quarter of their changes in gene expression. Likewise, plants fed on by the two species of aphids shared less than 10 percent of their changes in gene expression.

The plant responses to caterpillars were also very different than the plant response to mechanical wounding, sharing only about 10 percent of their gene expression changes. The overlap in plant gene responses between caterpillar and aphid treatments was also only 10 percent.

“The important thing is plants can tell the insects apart and respond in significantly different ways,” Schultz said. “And that’s more than most people give plants credit for.”

A sister study explored this phenomena further, led by former MU doctoral student Erin Rehrig.

It showed feeding of both caterpillars increased jasmonate and ethylene – well-known plant hormones that mediate defense responses. However, plants responded quicker and more strongly when fed on by the beet armyworm than by the cabbage butterfly caterpillar in most cases, indicating again that the plant can tell the two caterpillars apart.

The result is that the plant turns defense genes on earlier for beet armyworm.

In ecological terms, a quick defense response means the caterpillar won’t hang around very long and will move on to a different meal source.

More questions

A study this large has potential to open up a world of questions begging for answers.

“Among the genes changed when insects bite are ones that regulate processes like root growth, water use and other ecologically significant process that plants carefully monitor and control,” Schultz said. “Questions about the cost to the plant if the insect continues to eat would be an interesting follow-up study for doctoral students to explore these deeper genetic interactions.”

Frontiers in Plant Science published the primary study in its November 2014 issue. The sister study can be read here.

Big discoveries come in little (capsid) packages

It’s an understatement to say viruses are small.

But an average virus dwarfs the diminutive variety known as parvoviruses, which are among the most minuscule pathogens known to science.

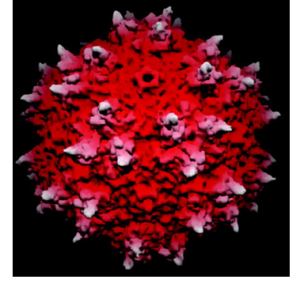

Tucked inside a protective protein shell, or capsid, parvoviruses contain a single DNA strand of about 5,000 nucleotides. If parvo’s genetic material is like an hour-long stroll around your neighborhood, a bigger virus like herpes is equivalent to walking from St. Louis to Columbia, Missouri.

“I joke that we can do the whole parvovirus genome project in an afternoon, because it’s just taking it downstairs and having it sequenced,” said David Pintel, a Bond Life Sciences Center virologist and Dr. R. Phillip and Diane Acuff endowed professor in medical research at the University of Missouri. “It’s the size of one gene in the mammalian chromosome.”

But that little stretch of DNA still has plenty of tricks up its sleeve.

Pintel has spent nearly 35 years studying parvo and is one of the world’s foremost experts on the virus, but he’s still plumbing the tiny pathogen’s depths.

His lab focuses on unraveling how parvo interferes with a host cell’s lifecycle and understanding the virus’ quirky RNA processing strategies.

“Even though the virus is small, it’s not simple,” David Pintel said. “Otherwise we’d be out of business.”

Over the last two decades, parvo has become an important tool for gene therapy, an experimental technique that fights a disease by inactivating or replacing the genes that cause it. Researchers enlist a kind of parvovirus known as adeno-associated virus as a gene therapy vector, the vehicle that delivers a new gene to a cell’s nucleus. Pintel helped suss out the virus’ basic biology, an important step for developing effective gene therapy.

A varied virus

The name ‘parvo’ comes from the Latin word for ‘small.’ But the virus’ size makes it a resourceful, versatile enemy and a valuable model for understanding viruses and how they interact with hosts.

Parvoviruses fall into five main groups. They infect a broad swath of animal species from mammals such as humans and mice to invertebrates such as insects, crabs and shrimp.

Canine parvovirus, or CPV, is perhaps the best-known type.

It targets the rapidly dividing cells in a dog’s gastrointestinal tract and causes lethargy, vomiting, extreme diarrhea and sometimes death. In humans, Fifth disease, caused by parvovirus B19, is the most common. This relatively innocuous virus usually infects children and causes cold-like symptoms followed by a “slapped cheek” rash. There is no vaccine for Fifth disease, but infections typically resolve without intervention.

Reading the transcript

Pintel surveyed the whole parvo family to understand its idiosyncrasies.

To study bocavirus – a kind of parvo recently linked to a human disease – Pintel looked closely at the dog version, minute virus of canines (MVC). MCV serves as a good model for the human disease-causing virus. While examining MVC, he noticed an unexpected signal in the center of the viral genome. The signal terminates RNA encoding proteins for the virus’ shell, a vital part of the pathogen.

Finding such a misplaced signal in the middle of a stretch of RNA is like coming across a paragraph break in the middle of a sentence.

Pintel knew the virus bypassed this stop sign somehow, because the blueprint for the viral capsid lies further down the genome.

To overcome this stop sign, this particular parvovirus makes a protein found in no other virus. The protein performs double-duty for the virus: It suppresses the internal termination signal and splices together two introns, or segments of RNA that do not directly code information but whose removal is necessary for protein production. Splicing the introns together ensures that the gene responsible for producing the viral capsid is interpreted correctly.

Viruses and hosts: a game of cat and mouse

The conflict between a virus and a host is a constantly escalating battle of assault and deception.

Viruses need a host cell’s infrastructure to replicate, but have to fool or outmaneuver its defenses.

Pintel discovered one example of this trickery in mice, where parvo triggers a cellular onslaught known as the DNA damage response, or DDR. This type of parvo co-opts that defense. Normally DDR pauses the cell cycle to keep damaged DNA from being passed on to the next generation of cells, but parvo exploits that delay, buying time for the virus to multiply.

“For many, many hours the cells are just held there by the virus while the virus continues to replicate,” Pintel said. “And then that cell never survives; the virus kills the cell. It’s that holding of the cell cycle — which is part of the DNA damage response — that the virus hijacks to hold the cell cycle. It’s really cool.”

Parvo’s small size makes it especially beholden to their hosts. But that can make them particularly revelatory for researchers.

“It’s a twofold thing,” Pintel said, “Because it’s a virus that’s dependent on the cell, when you learn how the virus is doing these things, you learn how the cell does those basic processes. If we’re looking at a viral-cell interaction, yes, we’re looking at it from a viral point of view, but on the other hand we’re trying to understand the basic cellular process.”

Uncovering such nuanced interactions is a painstaking, laborious process that often goes unheralded by mass media. But those fundamental discoveries provide the building blocks upon which other researchers depend, said Femi Fasina, a postdoc in Pintel’s lab.

“When you understand basic biology, people can walk on those advancements. Although we don’t see the impact immediately, such things lead to breakthroughs that will revolutionize a lot of things.”

A small question

Despite his deepening understanding of how parvo works, there remains one debate about the virus that Pintel deems beyond the scope of his research: Are the tiny slivers of DNA that comprise parvoviruses even alive?

“I think that’s a crazy question,” he said. “It’s semantics. The virus is a genome. It goes into a cell, it doesn’t do anything until it’s inside of a cell and then it does stuff.” So whether you write parvoviruses into the book of life depends entirely on how you define the word ‘alive.’

“I put that in the realm of philosophy,” Pintel said, “not the realm of science.”