By Sarah Rubinstein | Bond LSC

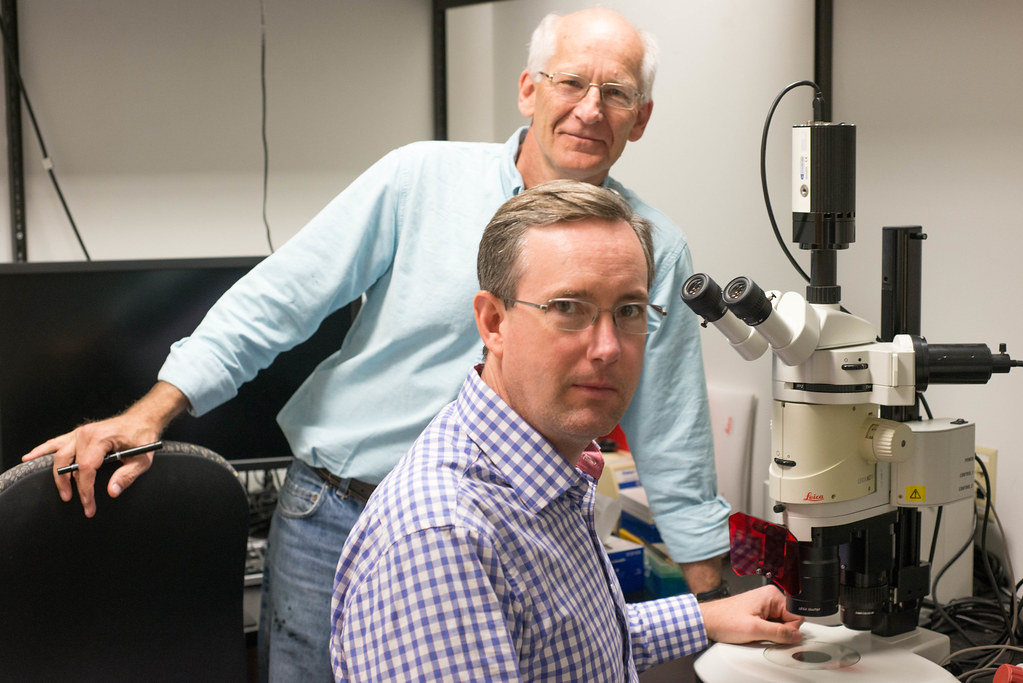

The African proverb “it takes a village to raise a child” can especially apply in science where that village includes mentors like Dong Xu, a Bond Life Sciences Center principal investigator, who has trained hundreds of students and collaborators.

Michael Arowolo, is among those mentored, having spent the past two years in Xu’s lab as a visiting scholar. In August, he will take that experience with him to Xavier University of Louisiana as a new assistant professor.

“Dr. Xu has really impacted me in so many facets of my life,” said Arowolo. “He has given me the privilege of tapping into his knowledge.”

The Nigerian native landed at Mizzou because around 40 scientific publications credited to him caught Xu’s attention, and he was invited to be a visiting professor in July 2022. He quickly stood out amongst other people Xu had worked with.

“In Africa, the research infrastructure is not as advanced as the U.S. In that environment, if he could publish that many papers, I was very impressed,” said Xu, also head of Mizzou’s Digital Biology lab. “He’s a self-starter, he actually takes initiative. I don’t need to motivate him to work hard.”

With experience from earning his Ph.D. in Nigeria, Arowolo scrambled between roles as a lecturer, researcher, exam officer and more. Working at the Bond LSC was a change of environment for him that he was excited to take on. He has made it a practice to come into the lab around 7:30 a.m. and leaves around 5 p.m. to meet his work needs. He spends his time mostly working on his computer, coding.

While visiting professors typically stay less than a year, Arowolo’s stay was extended because felt he still had more to contribute.

Arowolo’s research focus at Mizzou has been discovering innovations in biological pathways. To break it down, he collects information on gene interactions into a database using artificial intelligence to develop models such as Siamese Neural Network for identification of relevant genes. That information can help scientists access a multitude of information in one place to create targeted treatments and drugs for diseases.

“They won’t need to go through the back end and stress themselves with ‘What is all this computational jargon, what is all this coding?’” he said. “They can have a platform that they can easily interact with…and get the results they need to get.”

AI has become a major part of Arowolo’s work. He is developing his own large language model, using an advanced retrieval augmented generative mode that identifies and recognizes pertinent genes and describes its relationships with specific biological processes in human cells.

He recognizes how AI has been taking the world by storm, and he wants to use it to help people.

“Instead of just thinking that the world is over, that AI will take over, before AI takes over, we will tap into AI and be the speaker for AI,” he said.

Arowolo has also expanded past his computational work and has been collaborating with the Mizzou School of Medicine on a new project. His team proposed a medication dispensing machine that would help Alzheimer’s patients. His team is currently in the process of developing a product sellable to big companies like Amazon, he said.

“He transformed academic work into a commercial product,” Xu said.

But, on top of his research, Arowolo teaches undergraduate and graduate students and mentors Ph.D. students.

“It’s become a passion,” he said. “I’ve mentored over 100 students, and they are also doing well in their area of endeavor, most of them in Dr. Xu’s lab.”

Now, Arowolo will pass down what he’s learned from Dr. Xu to his new students at Xavier University of Louisiana in August.

Xu, on the other hand, is excited to see Arowolo take on this next step.

“I think the main reason you train people is not only so they will create a product but we hope to help them move onto a more independent position with a higher salary,” Xu said.

When Arowolo reflects on what he has accomplished so far, he envisions the work of him and his colleagues as the tool that will help people get access to the medications they need.

“I know there will be a day that will come, and we’ll have the right solutions to consider these diseases,” he said.

Chris Pires

Chris Pires

Yidong Liu is a senior research specialist from MU’s Department of Biochemistry that manages Shuqun Zhang’s lab. She also works on MAPKs and their role in plant defense responses such as pathogen-induced ethylene biosynthesis and phytoalexin induction.

Yidong Liu is a senior research specialist from MU’s Department of Biochemistry that manages Shuqun Zhang’s lab. She also works on MAPKs and their role in plant defense responses such as pathogen-induced ethylene biosynthesis and phytoalexin induction.