By Cara Penquite | Bond LSC

Ajay Gupta learned biology basics as a first year undergraduate on the bumpy bus ride from his small hometown to Punjab Agricultural University. Just a few hours’ ride, he made the most of his time before he returned home to help his family’s agricultural goods business.

Working extra hours in the margins of his time has become a habit for Gupta. Now a plant science first year Ph.D. student in the Bing Yang lab and Department of Plant Science and Technology Millikan Endowment recipient, Gupta starts his day around 9 a.m. and works on three plant science projects until night.

“My advisor has to sometimes push me out of the lab to go home,” Gupta said. “I have that fascination with science.”

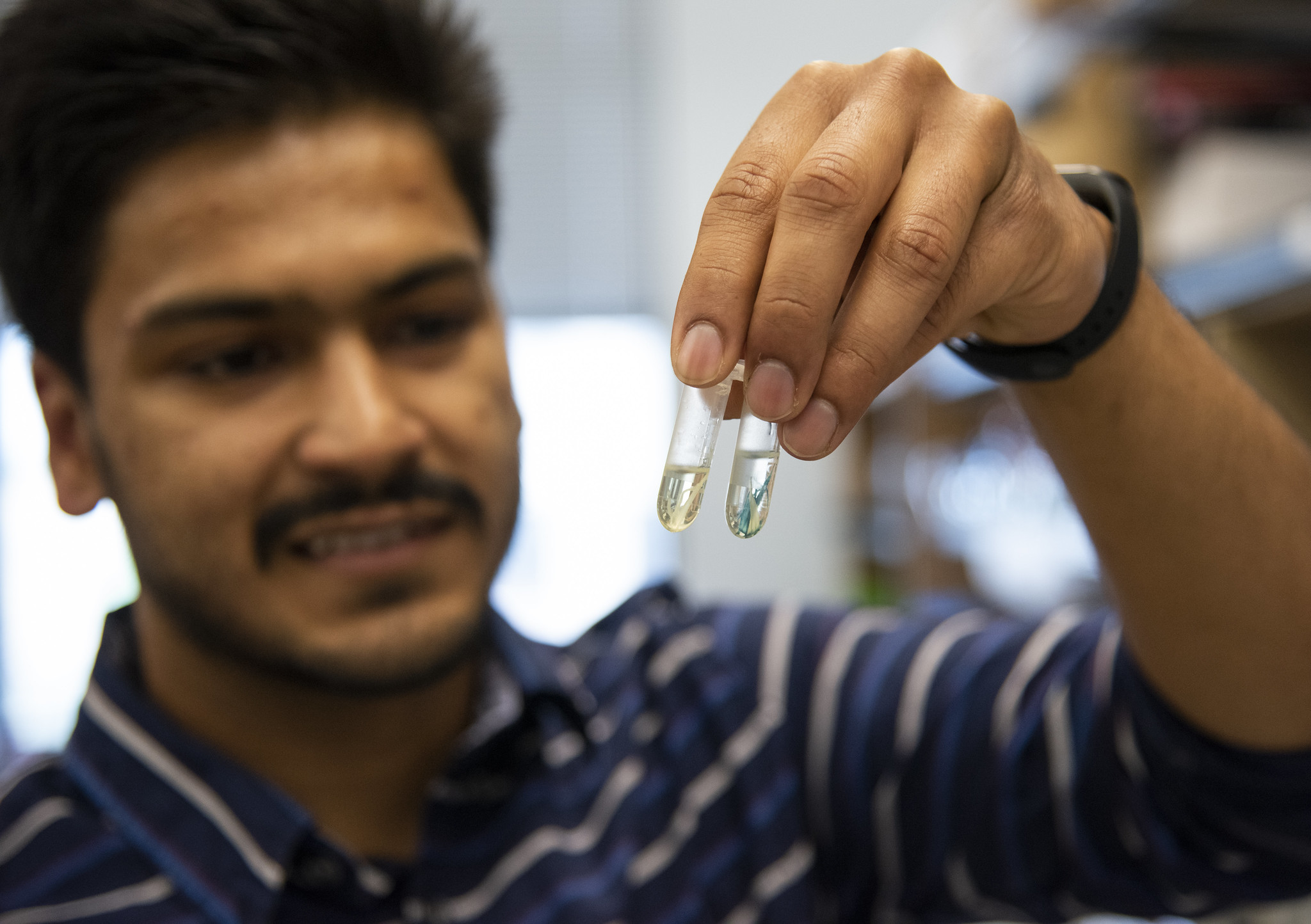

For his Ph.D. thesis project, he studies how rice plants fight off bacterial leaf blight — a disease caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae. This disease can devastate rice fields in Asia and other areas that depend on the staple grain. His research focuses on genes that help plants resist the deadly disease.

“The second project, which is very close to my heart, … is the development of CRISPR genome editing toolkit,” Gupta said.

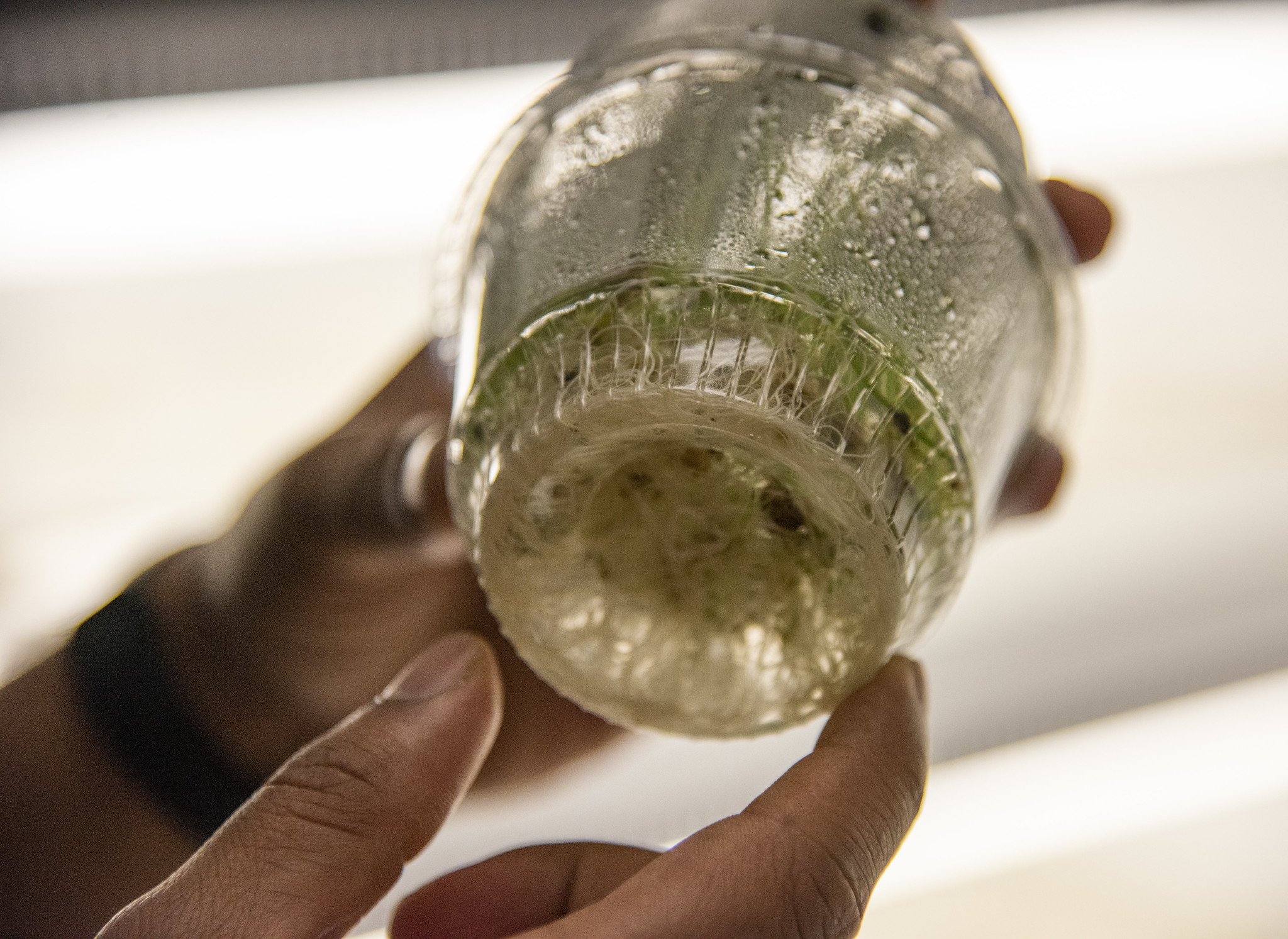

Gupta works to improve the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 in rice plants. Researchers currently modify chunks of DNA sequence with CRISPR, but Gupta’s goal is to modify the individual building blocks of DNA known as nucleotides. He simplifies the process to make gene editing easier for researchers with less CRISPR experience.

His third project started with self-taught skills rooted in a side passion. Gupta contributes to a global bioinformatics project investigating bacterial resistance genes in rice. By understanding the genetic make-up of plant resistance to disease, the researchers may find innovative solutions to prevent crop infections. Gupta’s input involves assembling the genome of a type of rice that is resistant to the pathogen that causes bacterial blight in rice.

“It’s a global project where everyone across the globe who uses that variety [of rice] can take advantage of that genome,” Gupta said.

Most of Gupta’s time is spent in the lab now, but Gupta started studying biology by accident. As an undergraduate he decided to major in agricultural biotechnology thinking there would be more math involved.

“It mentioned that it will have some math and some biology, and I knew nothing about biology,” Gupta said. “I said, ‘OK, it has math, I should go for it.’”

For the first year Gupta had six biology classes and one math class each semester.

“I said, ‘Oh my god, how am I going to survive,” Gupta said.

Gupta worked through basic biology courses in subjects like genetics, botany and zoology alongside his math courses. Then the math courses dropped off for the following years leaving Gupta’s schedule packed with biology classes.

“And then I started liking it,” Gupta said. “It seems more practical to me than math. I think if I would have gone to math I would have been in engineering, but I’m happy that I chose this path, and right now I’m working with plants which I love.”

Gupta’s small high school in his agricultural hometown left out many biology basics, but without the finances to attend a better school in another city Gupta was left to catch up at the university level while also helping his older brother at home.

“It was very challenging for the first year. Our financial situation was not great, so I had to support myself for my studies,” Gupta said.

Gupta returned every day to work as an accountant at his family’s small agricultural goods store to earn money for his education and to help.

“My father passed away when I was 15, and me and my brother who was 18 at that time, took care of our business without having much experience. So, I had to ride the bus four hours every day to go there and help my brother during my first year in bachelor because we could not afford at that time to hire somebody” Gupta said.

Back on their feet by his second year, Gupta continued working on weekends throughout the rest of his studies, and he only separated from the business when he left for his masters’ studies halfway around the world at South Dakota State University.

Gupta initially stayed with friends in South Dakota to soften the transition to the United States. Although difficult to live an ocean away from family, Gupta maintains relationships with his family.

“I talk with my mom almost every day. That’s a kind of an Indian or Asian thing. We are very close to our parents,” Gupta said.

Gupta started CRISPR research while working on his master’s degree at South Dakota State University. He focused on modifying wheat genes to increase yield and diversity, but on the side he also found a passion for bioinformatics.

“Most of this was self-learning, so I just found things on the internet and found out how they work and then made my own protocols and now have the pipeline,” Gupta said.

After this taste of research, Gupta was hooked. He applied to continue his studies as a Ph.D. student and asked Bing Yang, a collaborator with the lab’s wheat genetics research, for a letter of recommendation.

Instead, Yang asked Gupta to join his lab.

Gupta accepted his offer to continue working on CRISPR alongside expanding to more basic research — a change of pace from his previous work in applied agriculture.

“I want to develop a mindset where I can work on [basic science] well where there is little or no information and then I can think on my own,” Gupta said.

Gupta is the primary bioinformatics researcher in his lab and helps with data analysis for several projects alongside his bioinformatics project. While he spends most of his time hard at work on a research bench — and can often be seen walking across the Bond LSC atrium to the greenhouses late into the evening and over holidays — he also enjoys talking with lab mates.

“Sometimes, post [research] talks, we sit together and then I discuss with them if they have some problem I can try to help, and I do the same as well. If I’m having some problem I talk to them,” Gupta said.

Gupta plans to stay in academia and continue research and teaching others. He enjoys mentoring other students and also works on outreach to high school students.

“I love to do those things and talk to students, and maybe in some ways help this university as well,” Gupta said.

Gupta holds on to the inquisitive spirit that drove him to spend hours studying basic biology on the bus despite now learning in advanced research facilities.

“I love to talk with people [to] find out what they’re doing and if I can learn something out of it,” Gupta said. “Because a lot of the time our knowledge is limited and when talking to people you can get something new.”