On the weekends, the “tornado machine” was the highlight, one of Emily Giri’s favorite parts about her dad being a meteorologist.

“I was a very weird child,” Giri said. “In kindergarten, someone gifted me an encyclopedia about horses, and that was the best thing I had at the time.”

Between a tornado simulation and an encyclopedia, Giri identifies these memories as foundational moments in her life that helped her down a path toward science. But, she still had to choose which specialty to devote her time and energy towards.

Giri tussled with the idea of veterinary or medical school and many more career paths before she settled on research. She says she came to the decision because of the opportunities that awaits her in the field of virology.

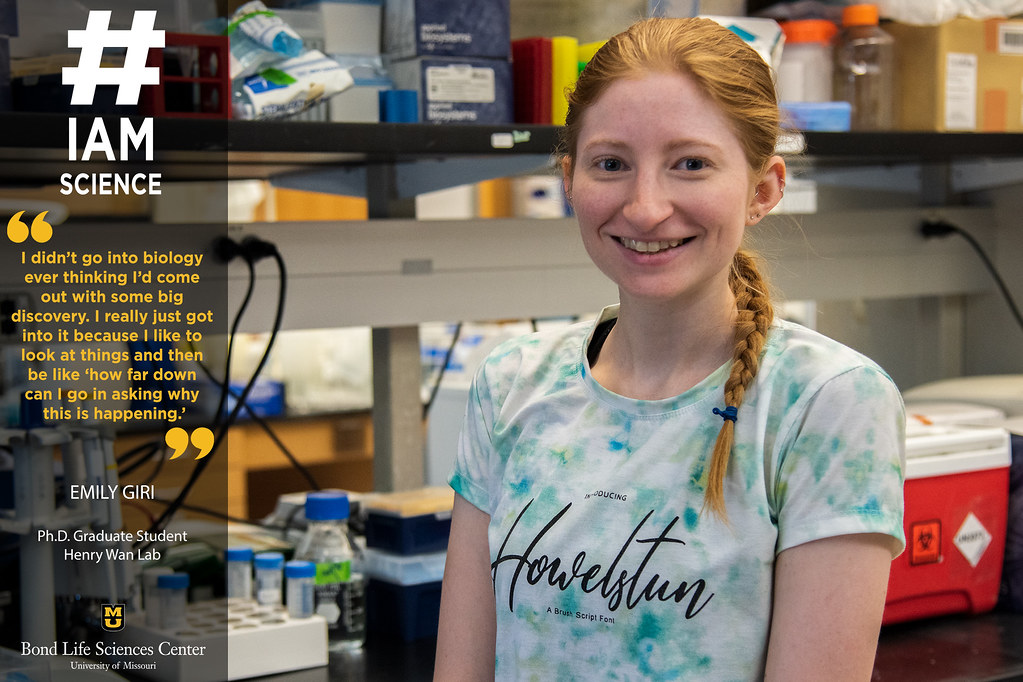

Giri is now a first-year Ph.D. graduate student in the Henry Wan lab at Bond LSC, but earned a bachelor’s degree in microbiology and virology at the University of Kansas. Her research aims to find out how the avian influenza virus jumps from birds to swine and eventually to humans.

Avian flu has been detected in 47 states and 58.7 million chickens and turkeys since January 2022, and tens of millions of commercial birds have been killed to limit its spread. Giri finds that there are not a lot of researchers who focus solely on virology, and her work aims to understand how the avian flu virus makes copies of itself.

“I’m just trying to get things to work before I really get into stuff,” Giri said. “So, I’m growing cells and trying to observe how and what they need to grow.”

To grow the cells Giri wants to study, she must come in every weekday to feed and monitor the cells and give them new media to materialize on “that makes them happy.”

Day to day, Giri is in the lab where she grows chicken eggs for 10 days. Giri also checks the humidity levels on a machine that rocks the eggs back and forth, similar to how a mother would rearrange them in the womb. For her research project, she pokes a small hole in the egg at a developmental point where the chicken cannot feel pain yet. She then inserts a small needle into the placenta, injects a small amount of avian influenza virus into the egg and watches as it replicates in the organism.

The beam of a flashlight shining through the eggshells is all Giri needs to check on the chicken eggs as the virus copies and pastes itself, each time with slight differences in its genetic code. When she verifies that this process is underway and the air sacs are at the top of the fetus as they should be, she moves on.

So why does Giri use chicken eggs specifically? Chicken eggs are useful in many different research projects because they can grow and be observed outside of the mother’s body.

She explains that the goal of her research is to gain more information about what changes must occur in the influenza genome to allow for it to jump from birds to swine. She swaps out or alters different parts of the genome in a strain of avian flu which is pathogenic to swine, in order to investigate what parts of its genome are important for replication in swine cells specifically.

Down the line, Giri hopes she can identify patterns in the genomes of avian influenzas that indicate if a particular strain is capable of jumping into swine. She hopes to learn more about how the virus transmits across species in order to decide whether or not they need to develop a vaccine for pigs.

Avian flu can jump from birds to other animals, so Giri uses swabs from wild ducks that have been infected, combined with other viruses, and injects the chicken eggs to learn how the virus makes more of itself. Later, she will infect swine cells with the same virus with hopes to learn how it transmits across species.

“This work doesn’t always feel fulfilling because a lot of experiments fail, usually on a daily basis,” Giri said. “But, it is very fulfilling the one time it does work because you have failed so many times before.”

Giri finds that the lab she works in and the people she has met through this project is what grounds her each day.

“I was the weird precocious kid, but I found a place where I fit,” Giri said.

Giri enjoys the differences between Columbia and Utah, where she is originally from. Hikes on nature-filled trails and new eateries are only some of the things that Giri and her husband like to discover around town.

“There’s a lot more culture here, with more Indian shops to get that type of food, and with my husband being from India that is important to us,” Giri said.

In her free time Giri works to learn Hindi, a language that her husband speaks fluently, and plays tennis each day after work. She uses her hobbies and her lab work to actively become more aware of the world around her, not to gain fame or fortune.

“I didn’t go into biology ever thinking I’d come out with some big discovery,” Giri said. “I really just got into it because I like to look at things and then be like ‘how far down can I go in asking why this is happening,’” Giri said.

This inquisitive mindset carries Giri through her work and probes her to dive into how the genomes of viruses can be useful in future vaccines. As she once flipped through her horse encyclopedia, Giri now combs through various pages of steps to her next experiment, doesn’t simply accept something as it is, and makes it a priority to ask “why” it is done in that way.