Plant scientist Ruthie Angelovici joins the Bond Life Sciences Center

By Jennifer Lu | MU Bond Life Sciences Center

Ruthie Angelovici clearly remembers her big eureka moment in science thus far. It didn’t happen in a laboratory. It wasn’t even her experiment.

At the time, Angelovici was in college studying marine biology. She had spent a year going on diving trips to figure out whether two visibly different corals were polymorphs of the same species, or two separate species.

A simple DNA test told her the answer in one afternoon.

“That’s the day I decided that there was a lot to be discovered, just in the lab,” Angelovici said. She switched majors and hasn’t looked back.

Better Nutrition in Crops

Angelovici studies the molecular biology of plants.

As a newly minted assistant professor in biological sciences at the Bond Life Sciences Center, her goal is to increase the nutritional quality of staple crops like corn, rice, and wheat.

Although these crops make up 70 percent of people’s diet across the world, Angelovici said, they aren’t very nourishing.

Corn, rice, and wheat are deficient in several key nutrients called essential amino acids. For example, if a person lived on wheat alone, they would have to eat anywhere from three to 17 pounds of the grain per day to reach the daily recommended amount for these nutrients.

Moreover, harsh growing conditions cause amino acids levels in plants to plummet—an increasingly grave problem as the earth’s climate gets warmer.

“If you think about the future, we’re going to face more droughts, more heat,” Angelovici said. “We need to figure out how we can maintain quality under those circumstances.”

Scientists have been trying to improve the nutritional quality of crops for years, whether through classical breeding or genetic engineering. The latter requires knowing which genes to alter.

Angelovici uses a technique called genome-wide association mapping. This allows her to link the natural variations within a particular trait — say, a special type of amino acids that are branched in structure — with the genes that affect this trait.

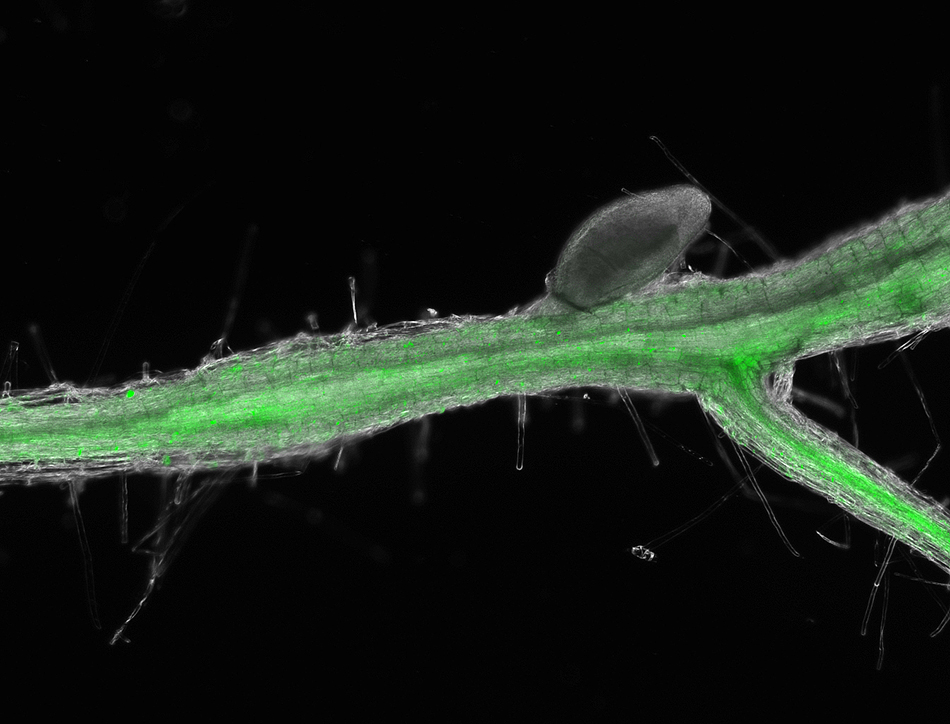

In previous studies, Angelovici chose Arabidopsis thaliana, which is popular among plant scientists for its simple genome and short life cycle, as her model plant.

She collected seeds from 313 varieties and burst them open, one seed type at a time, to release their contents. After separating the free amino acids from the rest of the seed pulp, she measured the branched amino acid levels — as a ratio to each other and to other amino acids — to build a nutritional profile that acts like a fingerprint for each plant.

Angelovici used this fingerprint to identify plants that shared similar traits. Then she scanned their DNA for any small genetic variations, or mutations, that plants had in common.

When she tallied up the frequency of each mutation in what is called a Manhattan plot, she found one particular variation that outstripped the others, standing out like a skyscraper over a city: a small section on chromosome 1 close to a gene called bcat2.

Angelovici then switched this gene off. When branched amino acid levels changed, it suggested that this trait was linked to the bcat2 gene.

However, Angelovici warned that often plants resist genetic tinkering. They lose viability, or cannot germinate seeds.

“We get yield penalty,” Angelovici says, “and the question is why?”

Metabolism, she explains, is like a network. “If you pull one way, something else is going to be affected.”

That’s where bioinformatics comes in handy. Angelovici uses an approach called network analysis to look at many pathways within the plant at once. This allows her to see the big picture, as well as the fine detail.

Moving to Missouri

Angelovici has being studying plant metabolism for ten years. Originally from Israel, she earned her PhD in 2009 under Gad Galili at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. Then, she continued her research as a postdoctoral fellow at Michigan State University.

She prefers working with plants to animals because plants are relatively easy to manipulate and breed. Also, she loves animals and at one point wanted to be a veterinarian.

Angelovici says she was immediately drawn to the University of Missouri, and is looking forward to collaborating with researchers at Bond LSC.

“There is a great program here, great plant people here,” she said. “So, Mizzou is spot on.”

Although she has found an undergraduate and a post-doctoral researcher to help her so far, the benchtops in her laboratory remain uncluttered save for some equipment, like glassware and a few gel boxes. Three pristine white lab coats hang neatly from hooks on the wall.

But Angelovici is not fazed by the enormous task of getting her lab up and running.

“I just love doing this. It’s like climbing a mountain,” Angelovici said, about the research process. “You do it slowly and then you feel like you’re going up and you are achieving more and you can see more. It’s really fulfilling.”

As for that big eureka moment, Angelovici says she doesn’t put much stock in it.

Then she laughs. “But maybe I will experience one, and then I’ll change my mind.”