By Allison Scott | Bond Life Sciences Center

“#IAmScience because I’ve been able to build upon my experiences and explore science in a new, exciting way.”

High school is a weird time for most people because everyone’s trying to figure out where they fit. Laura Greeley was ahead of her time, though.

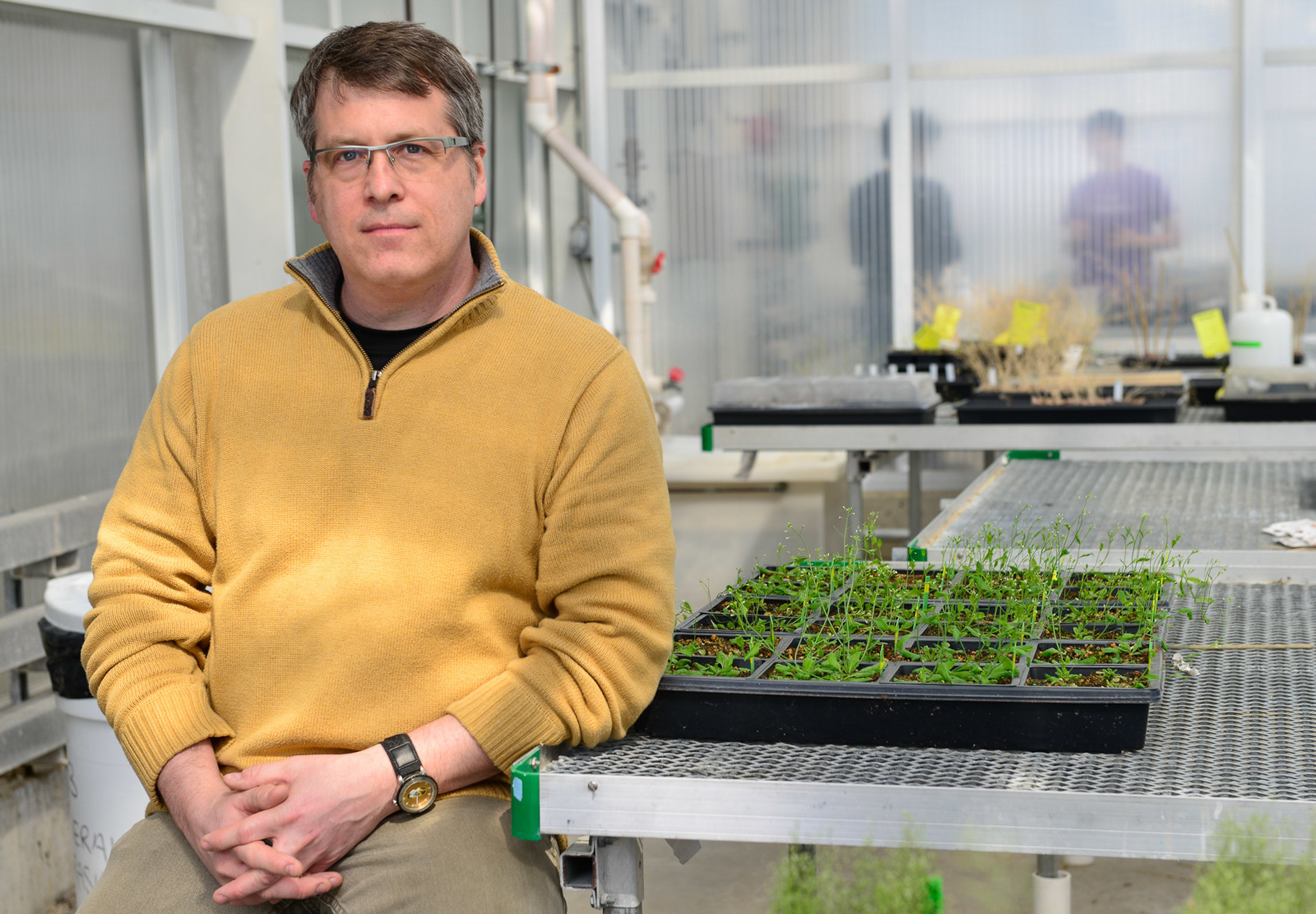

She uncovered important truths about her passions back then, and the postdoc in Scott Peck’s lab at Bond LSC hasn’t looked back since.

“In high school, I noticed that I had an affinity for chemistry and was inspired by biology, which helped me focus on the path that lead to where I am today,” Greeley said.

While no two days in the lab are the same, Greeley works on a main project centered around mass spectrometry, a technique that is sensitive enough to detect mass changes in molecules as small as a hydrogen atom. This can be used to identify many things, but in Greeley’s case, she wants to identify proteins and molecular changes in them.

“We’re looking at modulations in protein concentrations and possible modifications, such as the adding of a chemical bond,” Greeley said. “These modifications can affect how the protein functions.”

Working on such a small level has bigger applications. How these proteins change when under stressors like drought can tell Greeley and the team of scientists working on this project more about why roots are able to survive, even in the harshest of water conditions.

“We’re still at the exploratory point,” Greeley said. “We’re hoping to see changes in certain similarly functioning proteins that would indicate adaptive behavior.”

Ideally, Greeley would like to see the team uncover how corn root continue growing under harsh drought conditions. This would be an important stepping stone to engineering better crops to help prevent yield losses and, therefore, increase the food supply.

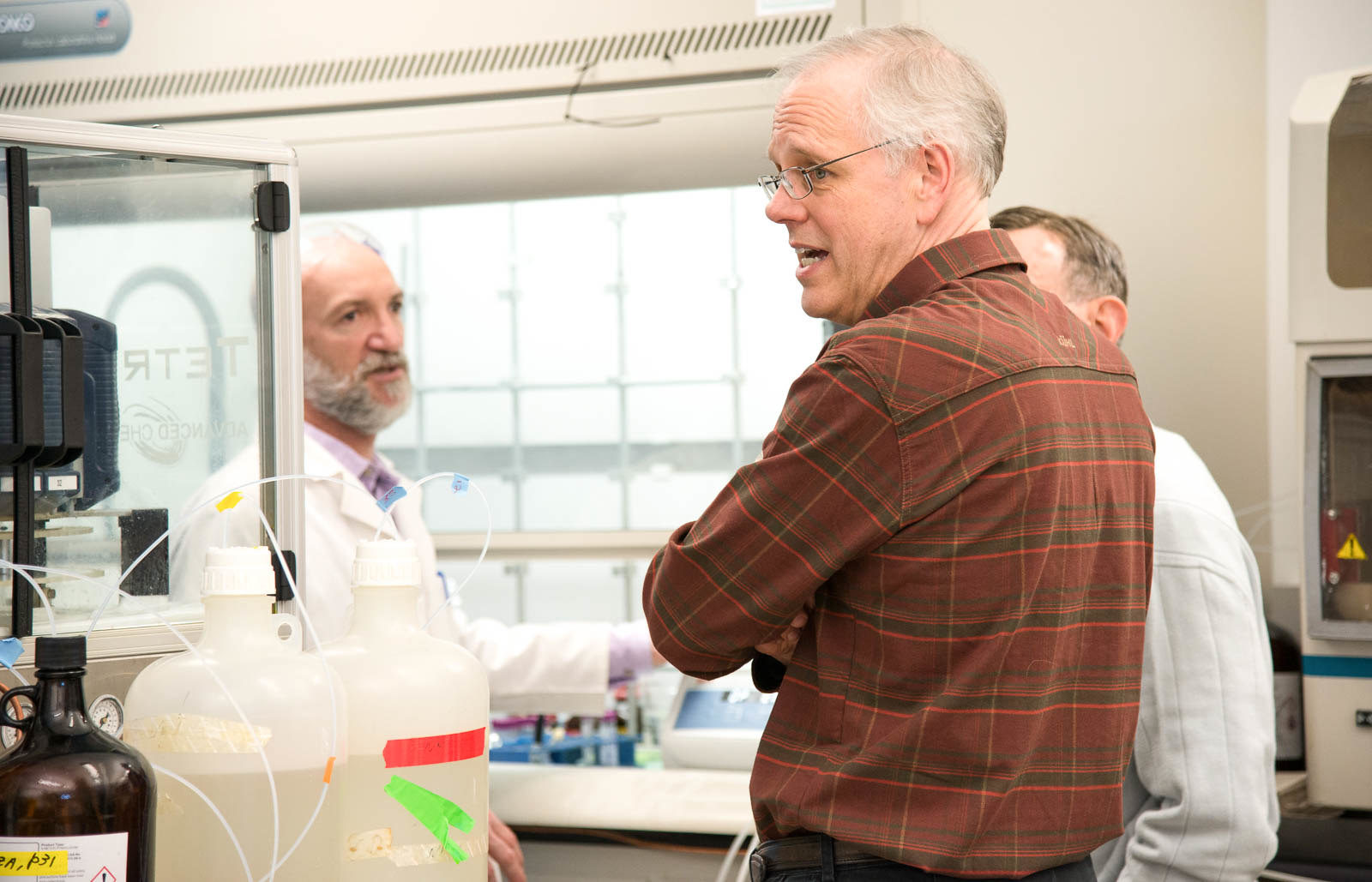

Teaching has also shared the stage with Greeley’s research. Thanks to the guidance of Peck, she’s working toward standing in front of students in the classroom.

“I expressed an interest in being an undergraduate professor one day, and he offered for me to lecture in one of his courses to see if I enjoy it,” Greeley said. “Incorporating that to my postdoc experience in the near future will help me to develop my skillsets for my career.”

Peck’s mentorship has helped Greeley focus her scientific zeal in the classroom and the lab.

“When things go wrong, he’s very supportive about trying to figure out what happened and how to fix it,” Greeley said. “He’s been pushing for more goal-oriented thinking lately, which is great for me.”

After finishing her postdoc, Greeley hopes to keep discovering more answers to the questions she has in the world of science.

“Thus far, each stage of my career has been even better than the last,” Greeley said. “I’m looking forward to that trend continuing.”