New web-based framework helps scientists analyze and integrate data

By Emily Kummerfeld | Bond LSC

Large-scale data analysis on computers is not exactly what comes to mind when thinking about biological research.

But these days, the potential benefit of work done in the lab or the field depends on them. That’s because often research doesn’t focus on a single biological process, but must be viewed within the context of other processes.

Known as multi-omics, this particular field of study seeks to draw a clearer picture of dynamic biological interactions from gigantic amounts of data. But, how exactly can scientists suitably weave multiple streams of information together, especially considering technology limits and other biological variables?

Trupti Joshi and her team are seeking to find a solution to that problem.

Joshi, as part of the Interdisciplinary Plant Group faculty, works on translational bioinformatics to develop a web-based framework that can analyze large multi-omics data sets, appropriately entitled “Knowledge Base Commons” or KBCommons for short. She describes KBCommons as “a universal, comprehensive web resource for studying everything from genomics data including gene and protein expression, all the way to metabolites and phenotypes.”

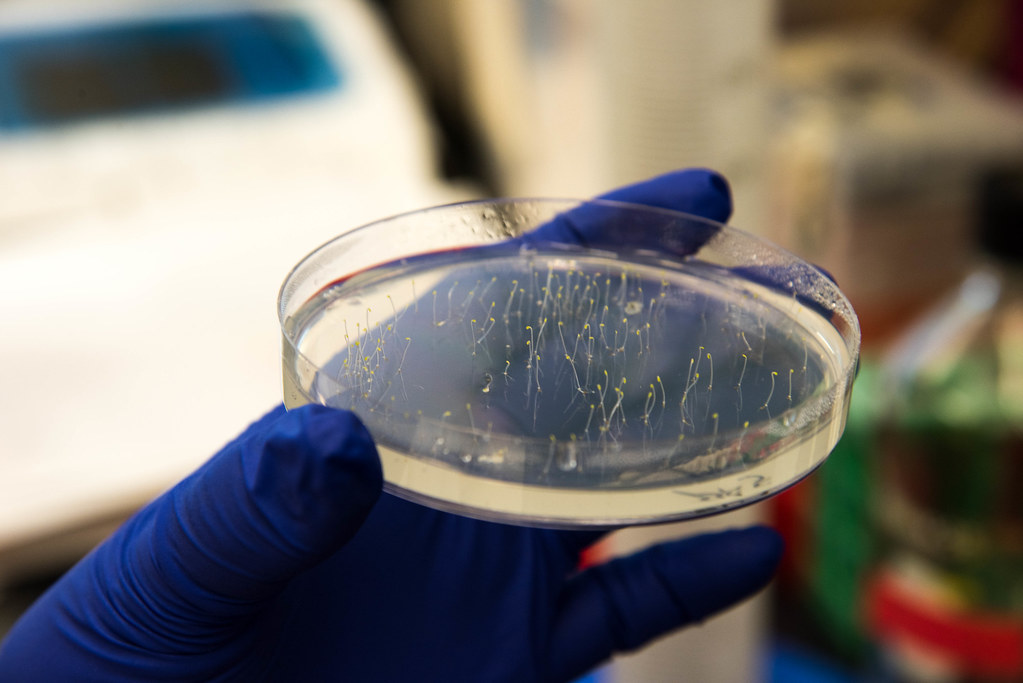

Her work began about eight years ago with soybeans. Dubbed the Soybean Knowledge Base (SoyKB), her team had developed a lot of their own data analysis tools for soybean research, but they realized the same tools could help research of other organisms. From there sprouted the Knowledge Base Commons, intended for looking at plants, animals, crops or disease datasets without the need to “reinvent the wheel” each time.

“Our main focus has been in enabling translational genomics research and applications from a biological user’s perspective, and so our development has been providing graphic visualization tools,” Joshi said.

Those tools provide an array of colorful graphics from basic bar graphs to assorted colored pie charts to help the researcher better analyze the data once data has been added to the KBCommons.

Colorful graphs and comparisons lets many researchers look past the lines of text and tables full of numbers that represent genes, plant traits or other experimental results, and making the interpretation of data much more easier and efficient.

One particular tool allows the researcher to look at the differential genes of four different comparisons or samples at the same time. Differential genes are the genes in a cell responding differently between different experimental conditions. For example, a blood cell and a skin cell both have the same DNA, however, some genes are not expressed in the blood cell that are expressed in the skin cell. With this KBCommons tool, a researcher can examine genes to see “what are the common ones, what are the unique ones to that, and at the same time look at the list of the genes and their functions directly on the website, without having to really go and pull these from different websites or be working with Excel sheets,” Joshi explained.

She envisions KBCommons as a tool to enable translational research as well. Users will be able to compare crops, such as legumes and maize for food security studies, or link research between veterinary medicine and human clinical studies for better therapies.

Intended for a wide range of users, Joshi is keenly aware of its potential users right here at MU.

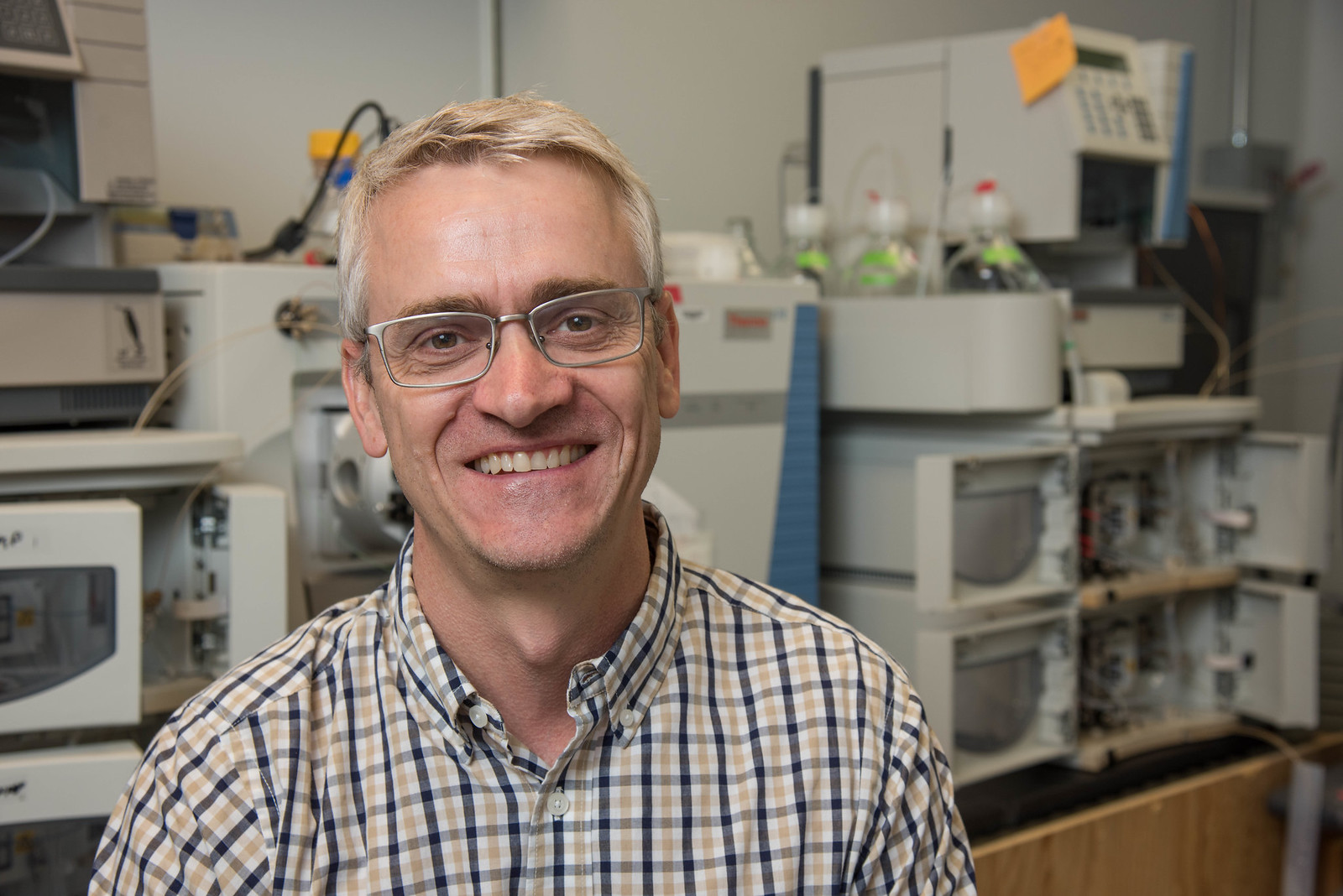

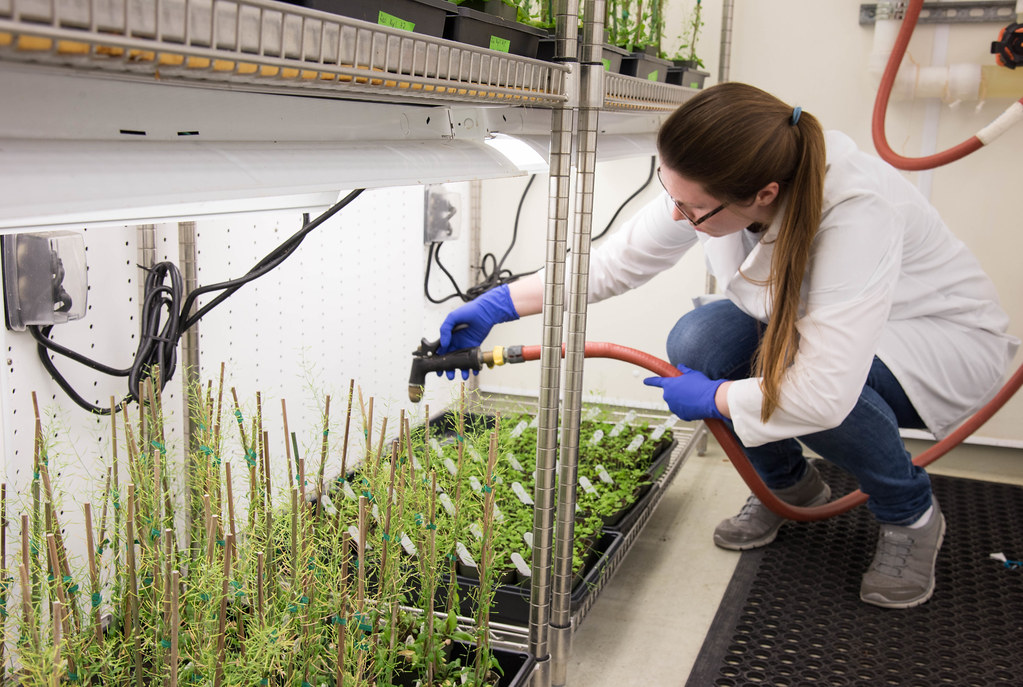

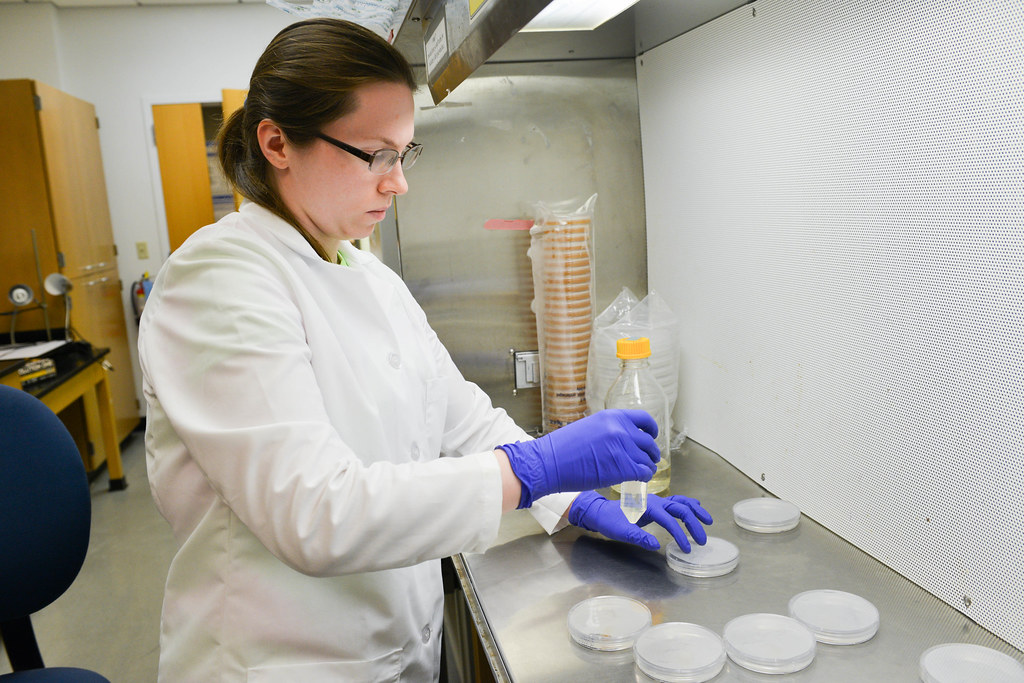

One current user of the Soybean Knowledge Base (SoyKB) system is Gary Stacey, whose lab at Bond Life Sciences Center studies soybean genomics and to date has been the longest user of the SoyKB resource. Like many researchers, Stacey explained the need for a program like SoyKB that can process enormous amounts of data.

“The reason it’s called “Knowledge Base” is the idea that we’re putting information in, and what we hope to get out is knowledge. Because information is different than knowledge,” he said, “we don’t just want to collect stamps, we want to be able to actually make some sense out of it…By having a place to store the data, and then more importantly have a place to analyze it and integrate it, it allows us to ask better questions.”

This is essential, given that one soybean genome is 1.15 GB in size, and one thousand soybean genome sequences could generate 30 to 50 TB of raw sequencing data and tens of millions of genomic variations (SNPs).

But such numbers are modest compared to the program’s true capabilities.

“The KBCommons system is so powerful that it can allow you to run thousands of genomes at the same time using our XSEDE gateway allocations,” Joshi said. “This whole scalability is a unique feature of KBCommons, which a lot of databases do not provide, and we are happy we have been able to bring that to our MU Faculty collaborators on these projects, so that they can really utilize the remote high performance computing (HPC), cloud storage and new evolving techniques in the field.”

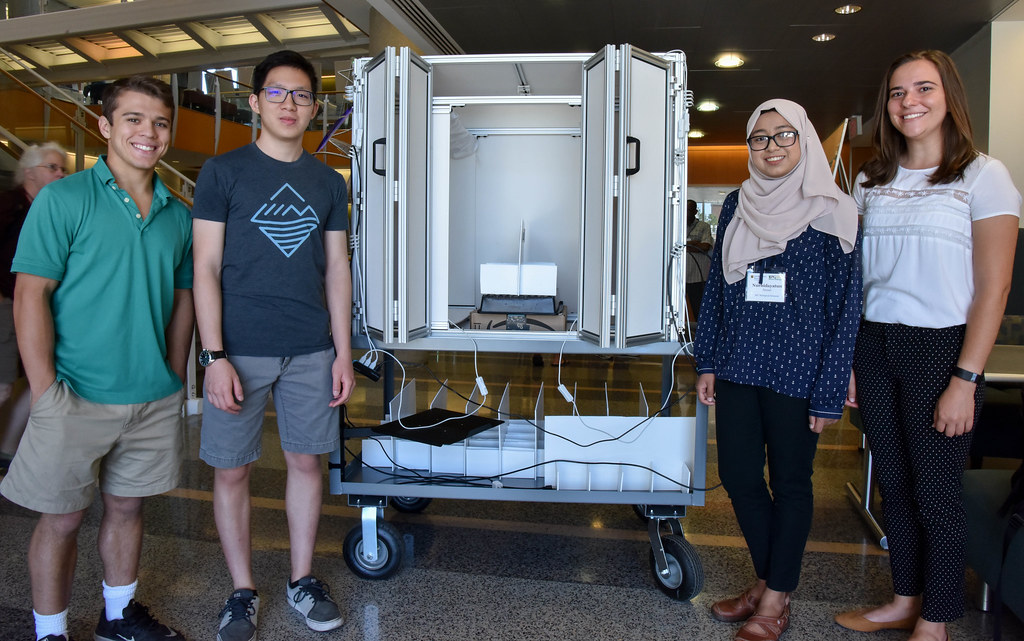

Mass data capability and colorful graphs aside, her favorite part is who exactly is designing the program.

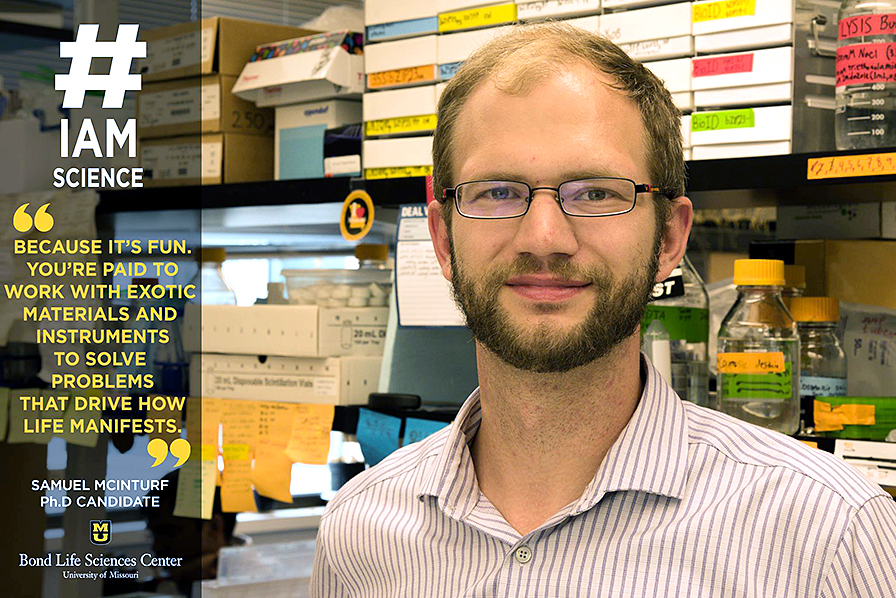

“What I like most about KBCommons is that it serves as a training and development ground and is developed by students, undergraduate and graduate students from computer science and our MUII informatics program.”

KBCommons is still under development, but publication and access for all users is planned for the end of this year or early 2018. Users will not only be able to view public data sets, but add their own private data sets and establish collaborative groups to share data.

Dr. Trupti Joshi is an Assistant Professor and faculty in the Department of Health Management Informatics, the Director for Translational Bioinformatics with the School of Medicine, and Core Faculty of the MU Informatics Institute and Department of Computer Science and the Interdisciplinary Plant Group.