Parkinson’s “trash pick-up problem”

It’s as if your recycling man quit his job and never came back.

Bags pile up to unexpected heights as waste continues to be generated and brought out to the curb. Day after day, the waste builds up as no one comes to pick them up.

For individuals with Parkinson’s disease, an accumulation of waste causes specific brain cells to die. The result is the onset of the disease.

But, instead of aluminum cans, plastics and paper, the waste that builds up in the brain cells of individuals with Parkinson’s is damaged mitochondria. Mitochondria are the cellular components that generate energy needed to keep cells alive.

When mitochondria is damaged and is no longer capable of making energy, it must be sent to the recycling center of a cell (called the lysosome).

Mark Hannink, a scientist at the Bond Life Sciences Center and professor of biochemistry at the University of Missouri, is peeling away the layers of this onion, one at a time.

His new research on a novel protein called PGAM5 (phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5) is pointing the way to finding a drug that can treat the disease.

Mitochondria suffer “wear and tear,” just like old cars

Mitochondria are endlessly helpful to a cell.

These powerhouses produce energy for a cell, control the cell division cycle and help regulate synapses. However, the mitochondrial proteins that produce energy eventually become damaged and no longer function properly.

“That’s part of the normal life cycle of mitochondria,” Hannink said. “Just like when the motor in an old car gives out due to wear and tear, that motor needs to be taken out and sent to the scrap dealer to be recycled and a new motor needs to be put in the car to keep it running.”

When mitochondria wear out they need to be sent to “recycling.”

“If that recycling pathway doesn’t work, the defective mitochondria will build up and will disrupt cell physiology, ultimately causing that cell to die” Hannink said.

Parkinson’s Disease is the clearest example of this recycling failure.

In early onset Parkinson’s, mutated proteins “forget” to take damaged mitochondria to the recycling center, resulting in build-up of toxic waste and, eventually, early onset of the disease.

“If the recycling mechanism isn’t functioning properly, those neurons die,” Hannink said.

Peptides behave like drug molecules

Hannink recently published research on the PGAM5 pathway in the Journal of Biological Chemistry along with MU graduate students Jordan M. Wilkins and Cyrus McConnell and fellow Biochemistry faculty member, Peter Tipton.

While its basic nature hides it from the view from the general public, this research takes a large step in the science of Parkinson’s disease.

Beyond defining the regulation of a pathway largely unstudied, their work discovered that a peptide regulates the pathway. Importantly, this peptide is able to alter the activity of the PGAM5 protein and stimulate an alternative recycling pathway for mitochondria.

Peptides are a clear signpost on a path toward drug development.

“Any time you can identify a biological process that is regulated by a peptide, that peptide becomes a lead candidate in the search for small, drug-like molecules that will act the same way,” Hannink said.

For Parkinson’s Disease, the goal is to find ways to repair the mitochondria recycling process.

“We propose that, by regulating PGAM5, it may be possible to restore mitochondrial quality control to dopaminergic neurons of patients with Parkinson’s and lessen the severity of the disease,” Hannink said.

What’s next?

While Hannink’s findings are exciting, there are also nuances to consider.

His research focuses on familial Parkinson’s disease, and it remains unknown whether sporadic Parkinson’s is also due to a defective mitochondrial recycling pathway. Sporadic Parkinson’s accounts for the vast majority of cases and typically affects older people.

It’s not clear if the PGAM5 pathway is also defective in those cases, Hannink said.

The next step of his research is to identify a small molecule that can regulate the PGAM5 protein in cells, just as the peptide did in his test-tube experiments.

Hannink thinks that development of a drug based on the PGAM5 pathway could be useful in restoring mitochondrial recycling in certain cells – like neurons affected in Parkinson’s – while blocking this recycling pathway in other cells, — like cancer cells.

The idea also needs to be tested using mice as a model system. The goal of those experiments will be to determine if the PGAM5 protein can stimulate alternative recycling pathways that can clean up and recycle damaged mitochondria pathway in neurons of mice.

“Mutant seeds” blossom in the pollen research field

The thought of pollen dispersed throughout the air might trigger horrific memories of allergies, but the drifting dander is absolutely essential to all life.

Science has long linked this element of reproduction with environmental conditions, but the reasons why and how pollen functions were less understood. Now lingering questions about the nuanced control of plants are being answered.

“Pollen is a very important part of the reproductive process and if we understand how pollen develops and how environmental stresses impinge on this process, we might be able to prevent crop loss due to high temperature or drought stress etc.,” said Shuqun Zhang, a Bond Life Sciences Center investigator.

Zhang has developed a new line of seeds that helped him and his lab identify an influential signaling pathway that triggers a chain reaction associated with normal pollen formation and function.

This research could lead to improvement to a plant’s response to disastrous environmental variables like drought to optimize pollen production and increase the production of food crops.

Seeds of success

Mutant seeds are the key to this work.

Instead of glowing green in the soil like you might see in a science fiction movie, they are providing important insight on plant reproduction and stress tolerance.

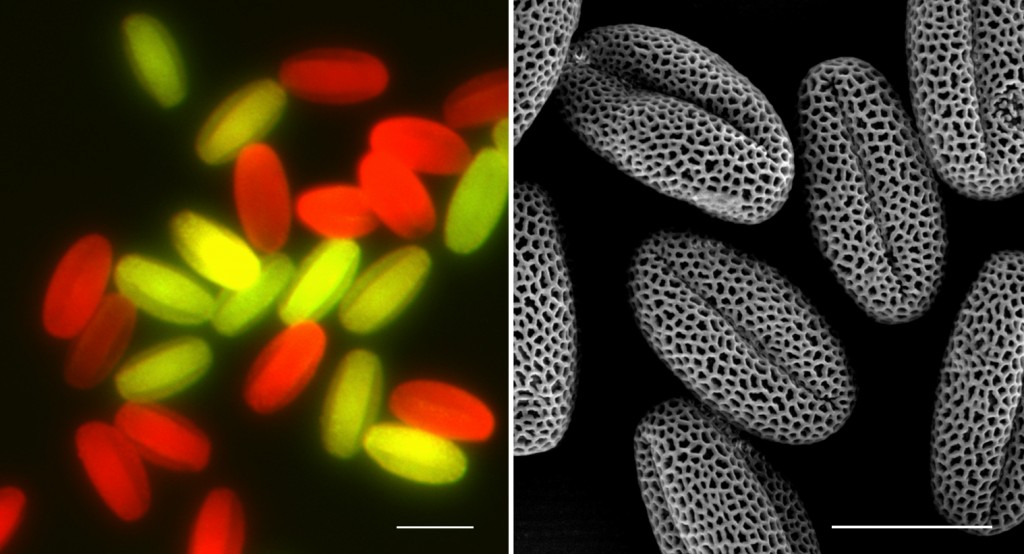

Zhang developed these plants from a mutant strain of Arabidopsis, a model plant used in scientific research. Certain genes were “switched off”to pinpoint where important pollen functions were signaled.

Using this mutant plant and seed system, Zhang found that WRKY34and WRKY2, two proteins that turn on/off genes, are regulated by MPK3and MPK6 “signaling” enzymes. These enzymes basically transform proteins from a non-functional state to a functional state, turning on specific duties or functions. Zhang, a professor of biochemistry at MU, began tinkering with the MPK3 and MKP6 pathways more than twenty years ago during his post-doc at Rutgers University.

Zhang’s research shows the newly identified MPK3/MPK6-WRKY34/WRKY2 pathway is a key switch in the hierarchy of the signaling system in pollen formation.

The research showed that the plant’s defense/stress response and reproductive process are linked, and the influential proteins MPK3 and MPK6 were part of the bigger WRKY34/WRKY2control pathway, which is activated in early pollen production.

The system is so useful that researchers across the country won’t stop asking for the seeds, Zhang said.

“We have a lot of requests for seeds,” Zhang said. “This is a very nice system to study pollen formation and function.”

The cascade of control

The functions of MPK3/MPK6 in plants can be compared to a “mother board” switch. The pathway — MPK3 and MPK6 —are part of a hierarchy of response, turning functions on or off. In other words, it’s a switch that controls a lot of different things. Controlling WRKY34/WRKY2 is one of the many roles played by MPK3 and MPK6.

“Whatever is plugged into it is what comes on,” Zhang said. “We are actually very, very interested in the evolutionarily context, how this came to be.”

This signaling process is just one of many in plants. MPK3 and MPK6 are two out the 20 MPKs, or MAPKs (abbreviated from Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases) in Arabidopsis. They control plant defense, stress tolerance, growth, and development including pollen formation and functions.

“We determined that this MAPK-WRKY signaling module functions at the early stage of pollen development,” Zhang said.

The “loss of function of this pathway reduces pollen viability, and the surviving pollen has poor germination and reduced pollen tube growth, all of which reduce the transmission rate of the mutant pollen,” according to the research.

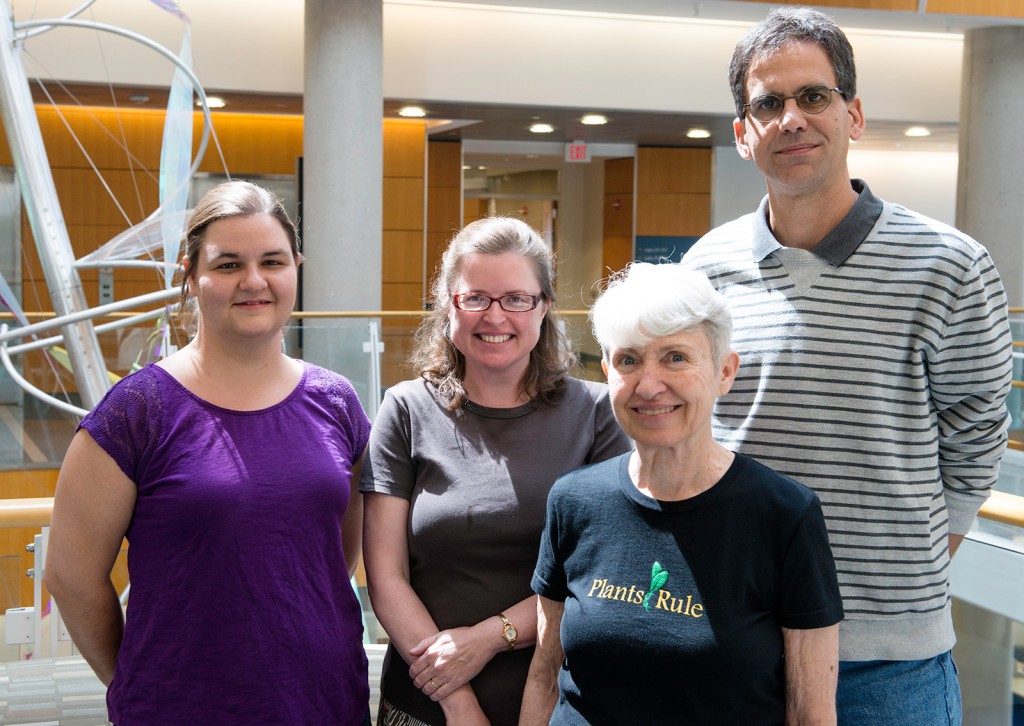

Zhang and his lab worked with the MU Division of Biochemistry and Interdisciplinary Plant Group on the research, which published in PLoS Genetics in June of this year.

A world without pollen production and defense

Without pollen, plants would not reproduce — there aren’t any Single Bars in the plant world (that we know of) — and if plant generations don’t propagate, there would be no air or food for human life to sustain.

“The factors such as heat and drought stresses cause problems to the plant’s normal developmental process and that’s how pollen fails to develop,” Zhang said. “If we understand the process, and know how environmental factors impact negatively the process, we can then make plants that can handle environmental stress better.”

Zhang and his lab continue to research the complexities of these pathways. Next on the quest is to answer how MPK3/MPK6 are involved in pollen functions such as guiding the pollen tube growth towards ovule to complete the sexual reproduction process in plants.

“It is possible that MPK3 and MPK6 are activated quickly in response to the guidance signals,” he said. “There’s still a long way to go because very few players in this process have been identified, we try to understand the biological process how they work together.” This research is in collaboration with Dr. Bruce McClure, also professor of Division of Biochemistry.

Read more:

1. PLoS Genetics (May 2014): Phosphorylation of a WRKY Transcription Factor by MAPKs is Required for Pollen Development and Function in Arabidopsis — Funded by a Hughes Research Fellowship and grants from the National Science Foundation.

2. Plant Physiology (June 2014): Two Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases, MPK3 and MPK6, are required for Funicular Guidance of Pollen Tubes in Arabidopsis — Funded by a National Science Foundation grant and a NSF Young Investigator Award.

#Sciku: Science and wordplay

This collection of Science Haikus were inspired by the #sciku Twitter campaign by Popular Science, which highlighted a few science haikus from readers. As a response, I rallied some of the scientists at the Bond Life Sciences Center to come up with haikus relating to their discipline of science.

The response was wonderful — Dr. Burke, of the immunology and virology core sent me a whopping 26 haikus — and many more scientists participated than I originally anticipated.

A haiku is a rigid form. It’s also a famously concise rhetoric, forcing the author to condense their meaning into the designated number of syllables (not always an easy task).

The funding environment in sciences is becoming tighter and tighter all of the time, too. There’s less money to go around and scientist are more than ever being asked to condense their grant proposals down to two or three pages (a contrast to the 15 page proposals of the 1990s).

Could it only be a matter of time until the National Institutes of Health will be giving money to research based on haiku proposals?

The only thing you need to read about Ebola today: An expert Q&A

News headlines seem to feverishly spread as if they were a pandemic of the brain.

Ebola hemorrhagic fever has been the most talked about disease of the year, appearing in thousands of headlines across the world since May. Through the noise of misinformation and sensationalism, fundamental information about the pandemic becomes harder to distinguish.

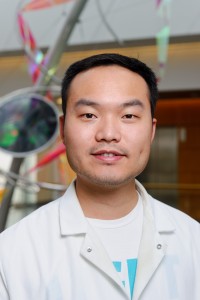

In an interview with Decoding Science on Tuesday, Shan-Lu Liu, MD, PhD, a Bond Life Sciences Center investigator who studies Ebola, weighed in on the latest news.

Liu, also an associate professor in the MU School of Medicine’s Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, and his lab are particularly interested in the early behaviors of the virus in transmission and how it can navigate around the host immune response.

Q: Talk about the transmission. Ebola doesn’t spread through air, but how easily can it be transmitted through fluids?

A: It’s hard to say. It’s really not like: touch an infected person and you got it. I don’t see that could happen so easily. As an RNA virus, it’s not that stable outside of the body, unlike hepatitis B virus (HBV) where you need to boil the virus for 10 minutes and it becomes not infectious. Because Ebola is not that stable, that should not be the reason why it’s so efficient to transmit.

I think the transmission is one of the biggest things it’s, you know, I don’t think we have a complete understanding. We do know that it spreads by contact through body fluids and many people don’t realize that the handling of the deceased — that’s very dangerous. Touching broken skin or mucous membranes like the nose and mouth is dangerous.

Q: Talk about the incubation period and how that relates to symptoms and spreading of the virus.

A: The incubation time is 2-21 days. At first, the person will have flu-like symptoms, so you know, that’s why it’s hard to notice in the early stages. Some doctors or nurses say ‘just give him antibiotics send him home.’ But in stage two, you get the hemorrhage and it gets serious. The mortality rate is high, from 50 to 90 percent.

I think the fatality is definitely related to the late stages of the disease, especially with the hemorrhaging fever. The early stages are almost unnoticeable but that’s the time transmission might spread easier through contact with an infected person’s fluid. Before symptoms, the virus doesn’t spread.

Q: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the virus could infect 1.4 million people in West Africa. Is this a realistic expectation?

A: You know, it could happen. It’s a prediction again, right? But I think the agency and the scientific community need to look at this prediction very carefully. What could be done in terms to prevent this from happening? It’s alarming.

Q: Last week, an article seemed to contradict with the CDC estimate. The headline: “Some good news about Ebola: It won’t spread nearly as fast as other epidemics.“ What do you make of that?

I don’t know, it’s hard for me to make a comment. Nobody knows. Things can always change. We didn’t expect to see a diagnosis in the United States — like this you know, this patient from Liberia was able to travel on a plane from virus country. Who can expect that? Anything can happen. There seem to have been some mishaps because he came from that area, right? Communication is more important now but it’s hard to predict because anything could happen.

Q: How has the Ebola virus behaved in previous outbreaks?

A: The first outbreak was in 1976 in Sudan and Congo — (Democratic Republic of Congo, known as Zaire at the time). It was from contaminated needles in a hospital and originally came from fruit bats — they are one of those animals that could transmit Ebola from animals to humans. The fruit bats transmitted the virus to primates, primates transmit to humans. It’s hard to notice in the early stages.

Editor’s note: The 1976 outbreak was the first occurrence of Ebola in humans. The outbreak affected one village, infecting 318 people that resulted in 280 deaths.

Q: Much of the media has reported a vaccine for ebola was delayed. How could this happen?

A: Drugs and vaccines are a little different. The Ebola vaccine was delayed, that’s for sure. That’s because, the vaccine on trial has to go through tedious steps to get approval and so thats why when this outbreak occurs the NIH (National Institutes of Health) decides to go ahead quickly. One of the things for ebola vaccine is um, the pharmaceutical companies and the industries are not interested in developing vaccines. Do you know why? It is not a big market. Only a hundred — or a thousand or more — people will be infected by ebola, unlike other vaccines like the HPV vaccination where 200 million people need it. The companies are not interested in developing it, because there’s no money in it.

A company needs to spend a lot of money to develop a vaccine, but they don’t see the market — the market can’t do it. But somebody needs to do it. Imagine if, if the virus spread like this, you know, unpredictable, it could be worse. In terms of therapy, the drugs and antibodies, we know they are really effective. And they are specific, so they can reach the market effectively.

Q: Will a drug be enough to prevent wide spreading of Ebola?

I think the companies and governments are speeding up to make those available. To see this prediction (the CDC 1.4 million estimate), they have to be prepared. People have put increasing attention on antibodies because a vaccine is not in the near future. So what’s the approach? A “therapeutic vaccine.” The so-called therapeutic vaccine is an antibody so you engineer, you use you know, molecular engineering technique to generate those antibodies and they can neutralize and block viral infection. It’s more realistic for Ebola and even for HIV. The HIV vaccine has failed so many times. So that’s why I think one of the new approaches is to use a new broad neutralizing antibody.

Q: Does Ebola stay in the body, like chicken pox?

A: Ebola do not cause latent infection. HIV can become latent and become chronic. So influenza virus, ebola viral infection and others normally do not lead to latency. I think for Ebola — for this type of infection — once you block the patient and clear the virus it should be good.

Q: Has the media done a good job in educating the public?

I think in terms of news coverage they are pretty careful. I looked at the news conference by the CDC director and by those doctors in Dallas, and when they make statements they are careful not to exaggerate and also give very cautious measurements. The news media need to be aware of the danger of the virus. In the meantime, you have to be aware of the possibility of being affected.

Again, I think it is a very important problem. It’s important to let the public know the situation. If you see people who have recently traveled from those West African countries, you have to be cautious — air travel is so common. But I think the media have generally done a good job.

Q: Has the government done a good job keeping the pandemic under control?

I don’t know what they do. The air travel is a problem. Intensified screening process, that should definitely be done. It’s very bad for people from the outbreak area, and I just hope that this community won’t be affected.

To control, they should be careful. A person with any sign of the disease — they need to be quickly monitored and treated.

Q: What’s the most important take-away message for the public?

A: I think it’s an important problem and we need to solve it urgently. I hope this outbreak will teach us a lesson in terms of how important emerging infectious viruses are as it comes and goes is to public health. Based on literature and reports, if people do not have obvious symptoms, they do not produce an infectious virus. The incubation time has a big range but again, we are still trying to understand the process better. Infection is a complex process. We need to better understand the viral transmission so I think for now, we need to be very cautious.

Liu and his lab do not work with the contagious Ebola virus on University of Missouri campus. All of the studies involve use of a recombinant or pseudotyped Ebola virus which is not infectious.

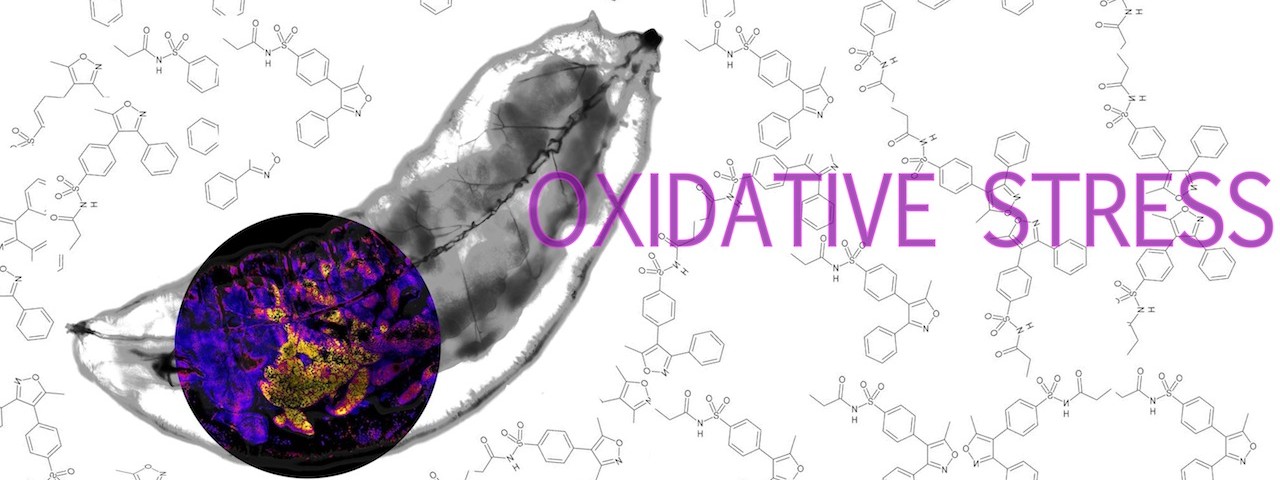

The search for oxidative stress treatment continues

University of Missouri research characterizes a novel compound

By Paige Blankenbuehler | Bond LSC

Your body has an invisible enemy.

One that it creates all on it’s own called oxidative stress, long thought of as an underlying cause of some of humanity’s most insidious diseases – cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s Disease, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Every day, our bodies are exposed to harmful free radicals known as reactive oxygen species as a result of our environment.

But, when something goes wrong with this energy extraction process, cells become inundated with reactive oxygen compounds that cause oxidative stress. The search for drugs to treat the problem have been ongoing, and with a complicated problem like oxidative stress, it’s all about finding the right combination.

Recent research by Bond Life Sciences Center investigator and Biochemistry Department Professor, Mark Hannink, provides a new approach for addressing the problem of oxidative stress and a starting point on developing a drug in pill form.

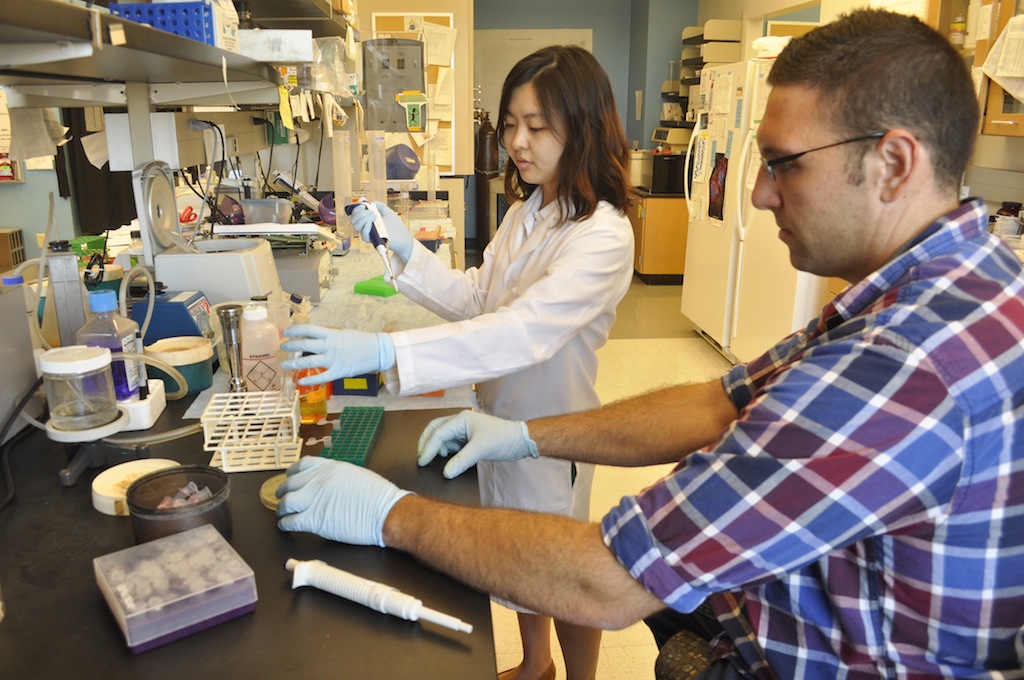

Mark Hannink and Kimberly Jasmer, a Ph.D. student in his lab, recently helped characterize a new molecule (called HPP-4382) that provides a novel way to treat oxidative stress. Their research was done in a partnership with High Point Pharmaceuticals, LLC, of North Carolina, where this new molecule was developed.

Oxidative stress can cause damage to the building blocks of a cell, resulting in excessive cell proliferation in the case of cancer or cell death in the case of neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s.

Often, the majority of stressors are actually created inside our own cells as a byproduct of how our cells extract energy from the food that we eat and the air that we breathe.

Understanding oxidative stress

Most simply, oxidative stress is an imbalance that happens when the body uses oxygen to produce energy.

Superoxide, a “promiscuous and nonspecific” compound produced as a byproduct of this process, is a highly reactive molecule that can damage DNA and other cellular components, Hannink said.

The superoxide molecule is a “free radical.” That means it’s especially promiscuous and reacts with many different types of cellular molecules, leaving destruction in its wake, he said.

That damage can lead to a long list of problems, including cancer or neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease.

In response to oxidative stress, the cell produces protective “anti-oxidant” proteins, which help remove the harmful reactive oxygen species and minimize damage.

But a heavy anti-oxidant response could be dangerous, too. The bottom line: it’s about maintaining a fine balance between “oxidants” and “anti-oxidants”.

Search for right combination continues

A drug that corrects the imbalance of oxidative stress could one day have wide applicability.

Jasmer developed a test to measure how specific compounds altered gene expression. The genetic response to oxidative stress has both an “ON” switch and an “OFF” switch.

Using this test, Jasmer determined how each compound affected specific genetic switches and, in turn, how the response to oxidative stress is regulated.

This test helped identify which molecules might be promising candidates for treating oxidative stress, leading them to one in particular that seemed to have the desired properties: HPP-4382.

But creating effective drugs is a long process of trial and error. Once molecules have been identified that show efficacy in lab-based assays, scientists try different combinations to increase their potency and drug-like properties, and High Point is currently testing other molecules that behave like HPP-4382.

The compound serves as a good starting point for researchers who are interested in understanding how oxidative stress affects cellular processes, such as cell proliferation or cell death.“Now we have a better understanding of what this compound is doing,” Hannink said. “This compound can be used to test different ideas of how the balance between oxidants and anti-oxidants is achieved in healthy cells and how perturbation of this balance can lead to different diseases.”

This research was published in PLoS One in July and was funded by High Point Pharmaceuticals, LLC.

Holding on: Bond LSC scientist discovers protein prevents release of HIV and other viruses from infected cells

Shan-Lu Liu initially thought it was a mistake when a simple experiment kept failing.

But that serendipitous accident led the Bond Life Sciences Center researcher to discover how a protein prevents mature HIV from leaving a cell.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published this research online Aug. 18.

“It’s a striking phenomena caused by this particular protein,” Liu said. “The HIV is already assembled inside the cell, ready for release, but this protein surprisingly tethers this virus from being released.”

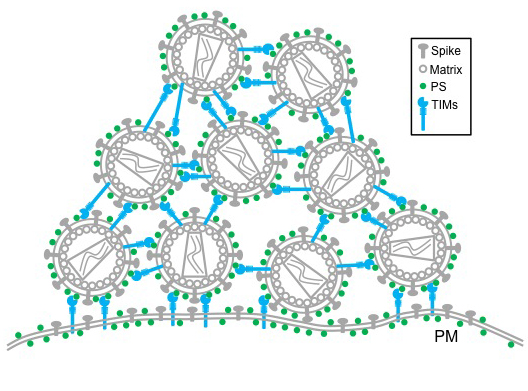

The TIM – T-cell/transmembrane immunoglobulin and mucin – family of proteins hasn’t received much attention from HIV researchers, but recent research shows the protein family plays a critical role in viral infections. From Ebola and Dengue to Hepatitis A and HIV, these proteins aid in the entry of viruses into host cells.

But its ability to stop the virus from leaving cells remained unknown until now. Liu’s lab stumbled onto this finding in November 2011 when trying to create stable cells for a different experiment. After two months of troubleshooting the HIV lentiviral vector – where genes responsible for creating TIM-1 proteins were inserted into a cell to create a stable cell line that expresses the protein – Liu was confident the vector’s failure was not only interesting but also important.

The lab spent the next two years trying to figure out what was happening. Minghua Li, an MU Area of Pathobiology graduate student, carried out experiments that confirmed the protein’s power to inhibit HIV-1 release from cells, reducing normal viral infection. His experiments showed TIM proteins prevent normal deployment of HIV, created by an infected cell, into the body to propagate.

TIM proteins stand erect like topiary on the outside and inside surfaces of T-cells, epithelial cells and other cells. When a virus initially approaches a cell, the top of each TIM protein binds with fats – called phosphatidylserine (PS) – covering the virus surface. This allows a virus, such as Ebola virus and Dengue virus, to enter the cell, infect and replicate, building up a population inside.

But as the virus creates new copies of itself, the host cell’s machinery also incorporates TIM proteins into new viruses. That causes problems for HIV as it tries to leave the cell. Now these proteins cause the viruses to bind to each other, clumping together and attaching to the cell surface.

“We see this striking phenotype where the virus just accumulates on the cell surface,” said Liu, who is also an associate professor in the MU School of Medicine’s Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology. “We consider this an intrinsic property of cellular response to viral infection that holds the virus from release.”

Further research is needed to determine overall benefit or detriment of this curious characteristic, but this discovery provides insight into the cell-virus interaction.

“This study shows that TIM proteins keep viral particles from being released by the infected cell and instead keep them tethered to the cell surface,” said Gordon Freeman, Ph.D., an associate professor of medicine with Harvard Medical School’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, who was not affiliated with the study. “This is true for several important enveloped viruses including HIV and Ebola. We may be able to use this insight to slow the production of these viruses.”

The National Institutes of Health and the University of Missouri partially supported this research. Additional collaborators include Eric Freed, PhD, senior investigator with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) HIV Drug Resistance Program; Sherimay Ablan, biologist with the NCI HIV Drug Resistance Program; Marc Johnson, PhD, Bond LSC researcher and associate professor in the MU Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology; Chunhui Miao and Matthew Fuller, graduate students in the MU Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology; Yi-Min Zheng, MD, MS, senior research specialist with the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center at MU; Paul Rennert, PhD, founder and principal of SugarCone Biotech LLC in Holliston, Massachusetts; and Wendy Maury, PhD, professor of microbiology at the University of Iowa.

Read the full study on the PNAS website and browse the supplementary data for this work. See more news on this research from the MU School of Medicine.

Critical transport: Bond LSC team finds boron vital for plant stem cells, corn reproduction

Carbon’s next-door neighbor on the periodic table typically receives little attention, but when it comes to corn reproduction boron fills an important role.

According to University of Missouri scientists, tiny amounts of boron play a key part in the development of ears and tassels on every cornstalk. The July 2014 edition of the journal Plant Cell published this research.

“Boron deficiency was already known to cause plants to stop growing, but we showed a lack of boron actually causes a problem in the meristems, the stem cells of the plant,” said Paula McSteen, a Bond Life Sciences Center researcher. “That was completely unknown before, and for plant scientists that’s an important discovery.”

Meristems are a big deal to a plant. These pools of stem cells are the growing points for each plant, and every organ comes from them. They are how plants can survive for 500 or 5,000 years, continuously making new organs in the form of leaves, flowers, and seeds throughout its life.

“When you mow your grass, it keeps growing because of the meristems,” said Amanda Durbak, first author on the paper and MU biological sciences post doc. “In corn, there are actually hundreds of meristems at the tips and all sides of ears and tassels.”

But without enough boron, these growing points disintegrate, and, in corn, that means vegetation is stunted, tassels fail to develop properly and kernels don’t set on an ear. This leads to reduced yield. Missouri and the eastern half of the U.S. are typically plagued by boron-deficient soil, an essential micronutrient for crops like corn and soybeans, indicating that farmers need to supplement with boron to maximize yield.

The tassel-less mutant

The team’s discovery started with a stunted, little corn plant that just couldn’t grow tassels, only created a tiny ear and died within a few weeks. These maligned reproductive organs piqued McSteen’s interest and her team of collaborators set out to figure out which gene was affected in this mutant plant. Graduate student Kim Phillips mapped the mutation to a specific gene in the corn genome involved in transporting molecules across the plant membrane.

But, what was this defect preventing the plant from receiving? Two experiments helped find the answer.

They started by looking at similar genes in other plants and animals. Simon Malcomber of California State University-Long Beach compared the gene – named the tassel-less gene after its mutant appearance – to similar genes in other plants and animals. He found that many were known to make a protein that transports boron and a few other elements.

From field to frog

To clinch this hypothesis, McSteen looked to Bond LSC scientist Walter Gassmann and the African clawed frog. Gassmann harvests eggs from these frogs and uses them to “test” the function of genes from both plants and animals.

“What we do is we inject the frog egg with RNA made in a test tube from the corn’s DNA,” Gassmann said. “The egg is a single, living cell that will actually use the message provided by this RNA to make the boron transporting protein and put it in the egg’s membrane.”

Frog eggs don’t naturally have the ability to transport boron, so an uninjected egg in a solution of boron can’t move the element into the cell.

“Corn RNA provides the egg with instructions to make a boron transporter protein, so the boron solution should move from outside to inside the egg,” Durbak said. “The egg should swell, showing this protein moves boron, and, in fact, these eggs swell so much they explode.”

A tank and a bucket guaranteed boron was the culprit. Durbak went back to the cornfield, watering some mutant tassel-less corn with boron fertilizer and other mutant plants with only water.

Only the ones given boron recovered and grew like normal corn plants, showing that the mutant corn has difficulties obtaining enough boron under natural, low boron conditions without this boron transporter. The boron content of the plants were later tested at the MU Research Reactor and the MU Extension Soil and Plant Testing Laboratory, affirming their observations.

A closer look

But, what does boron deficiency look like on a cellular level?

To see, the team collaborated with biochemist Malcolm O’Neill at University of Georgia. He looked at the cell walls in the plant and discovered that the pectin was affected. Pectin stabilizes the plant cell wall, and many home canners know pectin for its help in making jelly and jam solidify. Pectin is strengthened when boron cross-links two carbohydrates together, giving rigidity to the plant cell wall.

“The effect is that it locks in the cellulose, so without it plant cells won’t have nearly the stability,” McSteen said. “What we think is going on is that plant meristems basically disintegrate because they don’t have the support of pectin.”

While McSteen’s team identified the gene that controls the protein for boron transport into a cell, a research team from Rutgers University identified a gene that controls the protein that transports boron out of a cell. See more about both studies in Plant Cell’s “In Brief” section.

The next step in this research is to look more closely at what happens in these boron-deficient cells early on as they develop to understand the mechanism of boron action in stem cells.

A grant from the National Science Foundation supported this research.

In addition to their Bond LSC appointments, Paula McSteen is an associate professor of biological sciences in the MU College of Arts and Sciences and Walter Gassmann is a professor of plant sciences in the MU College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources.

A veterinarian abroad: Tanzania

In a second travel log from Bond LSC researcher Cheryl Rosenfeld, learn about the wildlife she encountered in Tanzania this summer. Through the North American Veterinary Community (NAVC), Rosenfeld furthered her veterinary education while encountering wildlife in their natural habitat. See more about the first leg of her trip to Rwanda here.

By Cheryl Rosenfeld

In the early morning hours, our group flew from Kigali, Rwanda to the Serengeti in Tanzania. As we began the descent to the dirt runway, we glimpsed our first sight of wildebeest and the awe-inspiring Serengeti plains and I soon boarded “tano,” Swahili for the fifth 4×4 in our convoy. “Tano” soon came to have special meaning, as there are many groupings of five to see in Tanzania: “The Big Five, The Ugly Five, etc.” Emanuel, whose life-long ambition was to attend college to be a guide, led us to see all of these groups of five and then some.

From the time we pulled away from the meeting spot, I started photographing animals on one side of the vehicle, but it seemed even more intriguing ones would appear on the other side of the road.

When the NAVC and our veterinary guide, Dr. Carol Walton, organized this trip, it was anticipated that the wildebeest would be in the Western corridor of the Serengeti but she was wrong. It’s no longer the case that the location of the wildebeest migrations can be projected with accuracy. Our lecture the first evening in Tanzania discussed how the wildebeest know to migrate and why past modeling of their migratory pattern is no longer accurate. Theories for the migratory nature of these animals include their ability to smell rain and/or changes in calcium concentrations in the soil. Wildebeest rely heavily on calcium to produce sufficient milk to nurse their calves that expend considerable energy keeping up with the herd.

In the past, the rains, like the wildebeest migration, would occur in similar sites and times throughout the year. Climate change has likely contributed to the rainfall in these sites being less reliable and correspondingly, compromised forecasting where the wildebeest will be located throughout the year. This year the wildebeest decided instead to migrate to the central Serengeti region. Thus, the next day we set off on an over-three-hour journey to this region.

While driving to find wildebeest we came upon new animals and birds including Coke’s Hartbeest, several Masai giraffe, and topis, which seemed to be splattered with oil. Finally, the wildebeest herds starting increasing in size until it reached a crescendo. As far as one could look in all directions there were wildebeest: males, females, and an abundance of baby calves. Eating alongside them were many zebras and their babies, with brown fuzzy fur along their back-end. It was the most amazing spectacle any of us had witnessed.

After seeing the vast wildebeest herds, we then came upon the elephants and lions, along with their babies. In the safety of the vehicle, we watched them engage in their natural behaviors for which no zoo experience can replicate. Both species were incredibly affectionate to the offspring and each other. In the case of the lionesses, each time the females, who were likely related, caught up with another that they had not seen in a short while would lead to emotional bouts of jumping on each other, caressing and licking. It was hardly the acts of a deadly predator. Yet, their existence rests on the wildebeest and other prey. With the wildebeest in this area, it seemed all life was flourishing at this time. A true paradise.

However, even paradise is subject to outside threats. One such threat is the massive poaching of elephants in Tanzania and surrounding African countries with 40,000 being killed last year alone. Prior to 2013, Tanzania had a “shoot to kill” policy for those caught poaching elephants or other endangered species. However, this rule has since been relaxed with the elephant numbers now in severe decline. At this unsustainable rate of poaching, the African elephant may go extinct in the wild in the next few decades.

While we did see some groups of elephants, the size of each matriarch-led group seemed less than those depicted in Sir David Attenborough and National Geographic documentaries. Moreover, one elephant that we came across, which I affectionately referred to as “Stumpy,” bore sad evidence of this brutal practice: He lost part of his trunk in a poacher’s snare. Without a full trunk, this elephant exhibited great difficulty grasping various plant items to place in his mouth.

Our subsequent travel took us to the famous “Olduvai (which should actually be Oldupai) Gorge,” one of the most famous paleoanthropological sites, including the Leakeys’ famous discovery. From there we traveled to the Ngorongoro Crater, a gigantic fracture of the earth’s crust that provides habitat for some 30,000 animals, including the most endangered black rhinoceros that only has 20 to 30 left in this area. The difference between the black and white rhino lies not in their coat color but a structural difference in their lips with black rhino possessing pointed and prehensile upper lip to browse on twigs and leaves. In contrast, white rhino possess a square upper lip to graze on the grasses below.

When Dr. Walton convinced us to set off at first light, around 6 a.m., our goal was to find one of these amazing creatures. Once again, with Emmanuel’s assistance and eagle eyes, what started out as a black dot far off in the horizon began to morph into a recognizable rhinoceros. In utter delight, we strained our necks and photographed as this beautiful animal continued to move along and forage in the distance. It would be inhumane to allow this animal to go extinct. In the case of the rhino, many Asian countries believe that its horn increases male libido, which has never been proved to be the case. This mistaken notion possibly originated from the fact that male rhinos copulate with females for several hours duration. This behavior is, however, not transferrable to men who consume any part of a rhino.

The list of species we saw in Tanzania continued to grow while we drove around the crater with black-backed and common jackals following alongside our vehicle, eland and grants gazelles grazing in the plains, flocks of greater and lesser flamingoes observed in the distance, and more lion prides and spotted hyenas.

The next day, we had our final farewell lunch at the famous Arusha Coffee Lodge, where US presidents have dined. We then set off on our long journey back to the US.

All of us were impacted by the creatures and sites we saw. One male veterinarian, who seemed gruff and quiet for most of the expedition, put it best the night before we left. He unexpectedly stood up after our last lecture and proclaimed that he signed up for the expedition more as an escape from the daily grind of being a veterinarian. However, the trip made such as impression on him to the point that he realized that part of the veterinarian oath on “relieving animal suffering” should include standing up and advocating on their behalf to prevent their brutal murder, as previously occurred in the case of the gorillas and is ongoing for elephants and rhinos. All of us were moved by his emotional comments and the tears welling up in his eyes. Our group was indeed fortunate to see these majestic animals, while they still exist, in their natural environments. I hope there is a wake-up call for nations to come together to prevent their extinction.

Viruses as Vehicles: Finding what drives

By Madison Knapp | Bond Life Sciences Center summer intern

Modern science has found a way to turn viruses —tiny, dangerous weapons responsible for runny noses, crippling stomach pains and worldwide epidemics such as AIDS— into a tool.

Gene therapy centers on the idea that scientists can hijack viruses and use them as vehicles to deliver DNA to organs in the body that are missing important genes, but the understanding of virus behavior is far from exhaustive.

Marc Johnson, researcher at the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center and associate professor of molecular microbiology and immunology in the MU School of Medicine, has been building an understanding of viral navigation mechanisms which allow a virus to recognize the kind of cell it can infect.

Johnson’s research specifically explores the intricacies of the viral navigation system and could improve future direction of gene therapy, he said.

Turning a virus into a tool

Conceptualized in the 1970s, gene therapy was developed to treat patients for a variety of diseases, including Parkinson’s, leukemia and hemophilia (a genetic condition that stops blood from clotting).

To treat disease using gene therapy, a customized virus is prepared. A virus can be thought of as a missile with a navigation system and two other basic subunits: A capsule that holds the ammunition and the ammunition itself.

The viral genetic material can be thought of as the missile’s ammunition. When a cell is infected, this genetic material is deployed and incorporated into the cell’s DNA. The host cell then becomes a factory producing parts of the virus. Those parts assemble inside the cell to make a new virus, which then leaves the cell to infect another.

The capsule is made of structural protein that contains the genetic material, and the navigation system is a protein that allows the virus to recognize the kind of cell it can infect.

Viral navigation

Gene therapy uses viruses to solve many problems by utilizing a virus’ ability to integrate itself into a host cell’s DNA; to do this successfully, researchers need to provide a compatible navigation component.

In the body, viruses speed around as if on a busy highway. Each virus has a navigation system telling it which cells to infect. But sometimes if a virus picks up the wrong type of navigation system, it doesn’t know where to go at all.

“What you can do is find a virus that infects the liver already, steal its navigation protein and use that to assemble the virus you want to deliver the gene the liver needs,” Johnson said. “You can basically take the guidance system off of one and stick it onto another to custom design your virus.”

But this doesn’t always work because of incompatibility among certain viruses, he said.

Johnson and his lab are working to understand what makes switching out navigation proteins possible and why some viruses’ navigation systems are incompatible with other viruses.

“I’m trying to understand what makes it compatible so that hopefully down the road we can intelligently make others compatible,” Johnson said.

The right map, the right destination

Johnson creates custom viruses by introducing the three viral components—structural protein, genetic material, and navigation protein—to a cell culture. The structural protein and genetic material match, but the navigation component is the wild card. It could either take to the other parts to produce an infectious virus, or it could be incompatible.

Johnson uses a special fluorescent microscope to identify which viruses assembled correctly and which didn’t.

A successful pairing is like making a match. If a navigation protein is programmed to target liver cells, it’s considered a successful pairing when the virus arrives at the liver cell target location.

The scope of gene therapy continues to widen. Improved mechanisms for gene therapy, and greater knowledge of how a navigation protein drives a virus could help more people benefit from the vehicles viruses can become.

Johnson uses several high-profile model retroviruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which affects an estimated 35 million people worldwide each year, according to the World Health Organization.

Understanding nuances of HIV in comparison to other viruses allows Johnson to pick out which behaviors might be common to all retroviruses and others behaviors that might be specific to each virus.

Johnson said his more general approach makes it easier to understand more complex viral features.

“If there are multiple mechanisms at work, it gets a little trickier,” Johnson said. “My angle is more generic, which makes it easier to tease them apart.”

Supervising editor is Paige Blankenbuehler