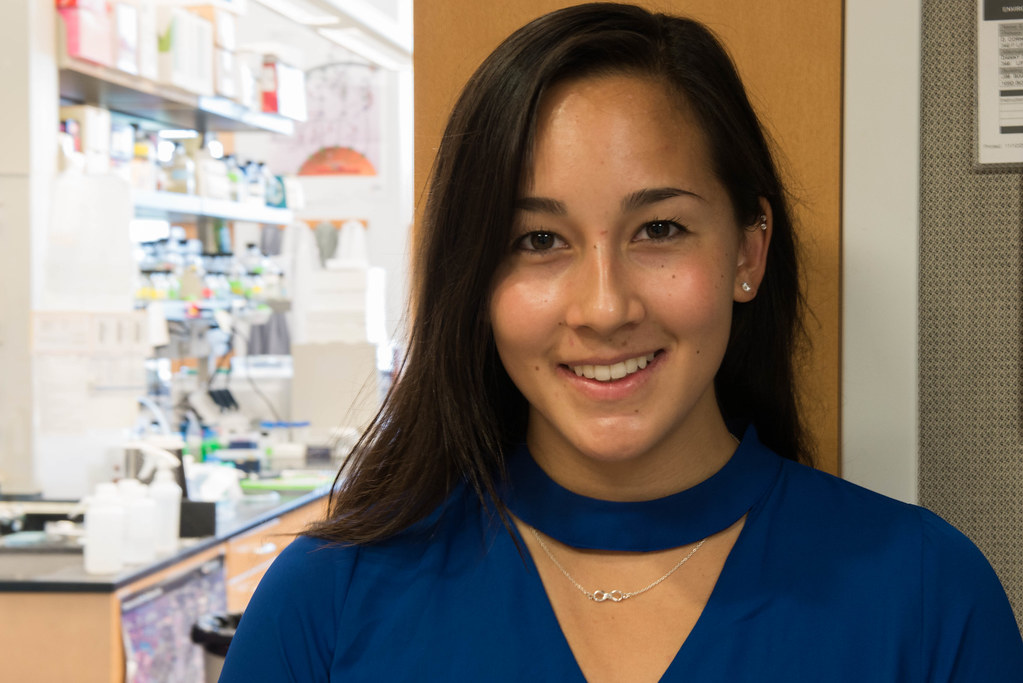

Graduate Researcher Sarah Unruh explores the essential role of fungi in orchid germination

By Emily Kummerfeld | Bond LSC

The blooms of orchids are unmistakably beautiful, and how they reproduce has fascinated biologists for centuries.

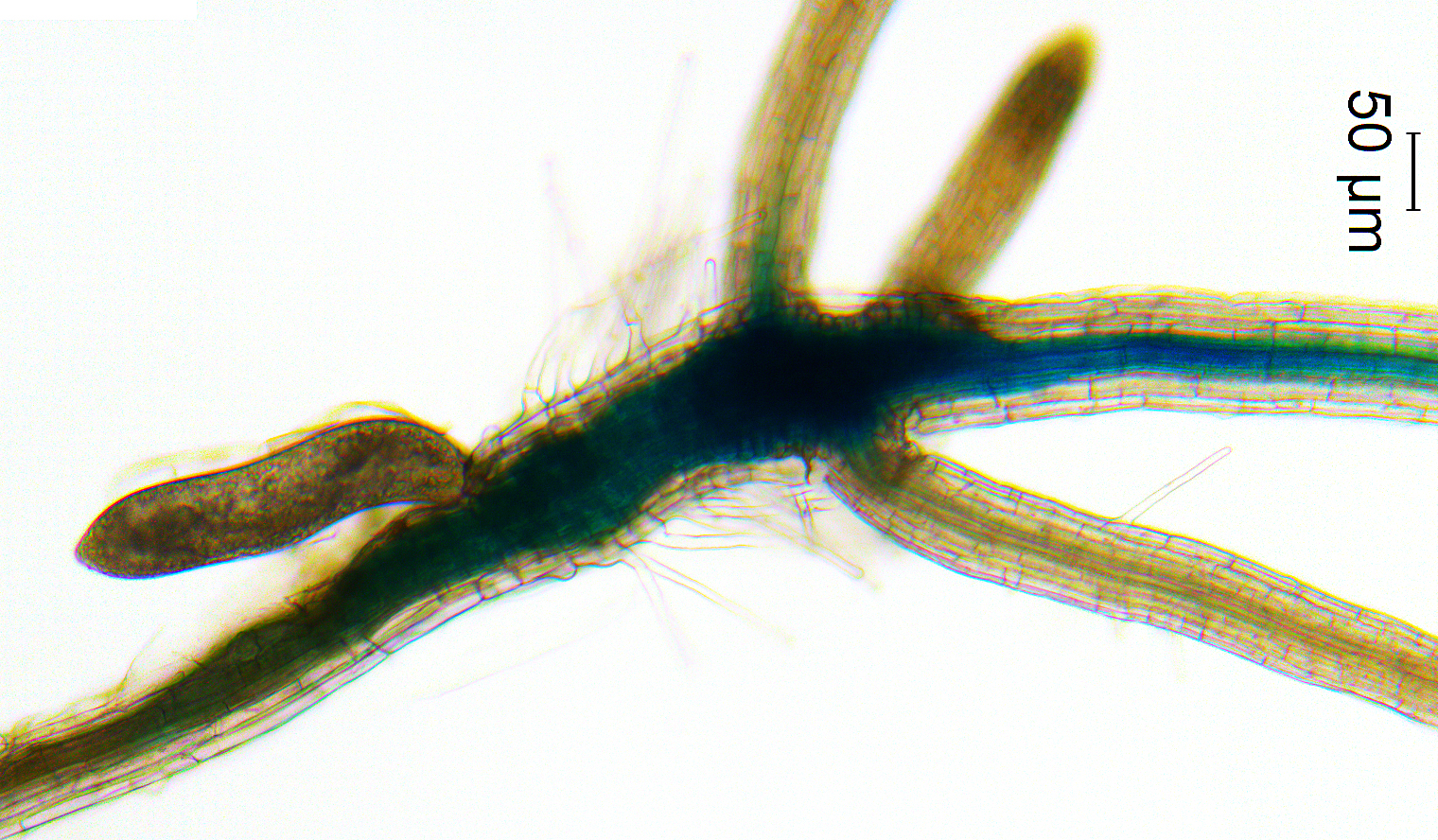

But, orchids might not even exist if not for the help of fungus. Up to 30,000 species of orchids require the intervention of fungi since their seeds do not contain the necessary nutrients to sprout.

Sarah Unruh, a fifth-year biological sciences PhD student in the lab of Bond LSC’s Chris Pires, seeks to discover and record the specific types of fungi utilized by many orchid species. By studying their specific genetic expressions, she hopes to uncover what allows these fungi to interact with orchids in this way, how these fungi are related to each other and what genes each organism is expressing with and without each other.

“The main question for me is, what is the nature of this relationship? Is it more mutualistic or parasitic? You don’t often get something for nothing, so why is the fungus participating in this relationship? Most fungi that live in plant roots receive carbon from the plant. Orchid fungi are doing the opposite and that is weird. I want to know how this relationship works,” Unruh says.

Unruh first studied orchid evolution and how each orchid species related to each other genetically. “My assumptions of what a plant was were so violated by orchids and it still fascinates me! So many orchid species grow on trees, many don’t have leaves, some species never even turn green or photosynthesize.”

This focus soon evolved into her interest in the relationship between orchid plants and fungi. Fungi are neither plants nor animals, and have their own branch on the eukaryotic family tree. They are nonetheless essential to plant biology, “eighty percent of plant species have beneficial fungi in their roots,” says Unruh.

Many orchids are technically classified as epiphytes, which means they grow on the surface of another plant and get all their food and water needs from the air, rain and what accumulates nearby. That doesn’t leave a lot of extra nutrients to put into seeds, which typically need the store of food to sprout and grow its first leaves.

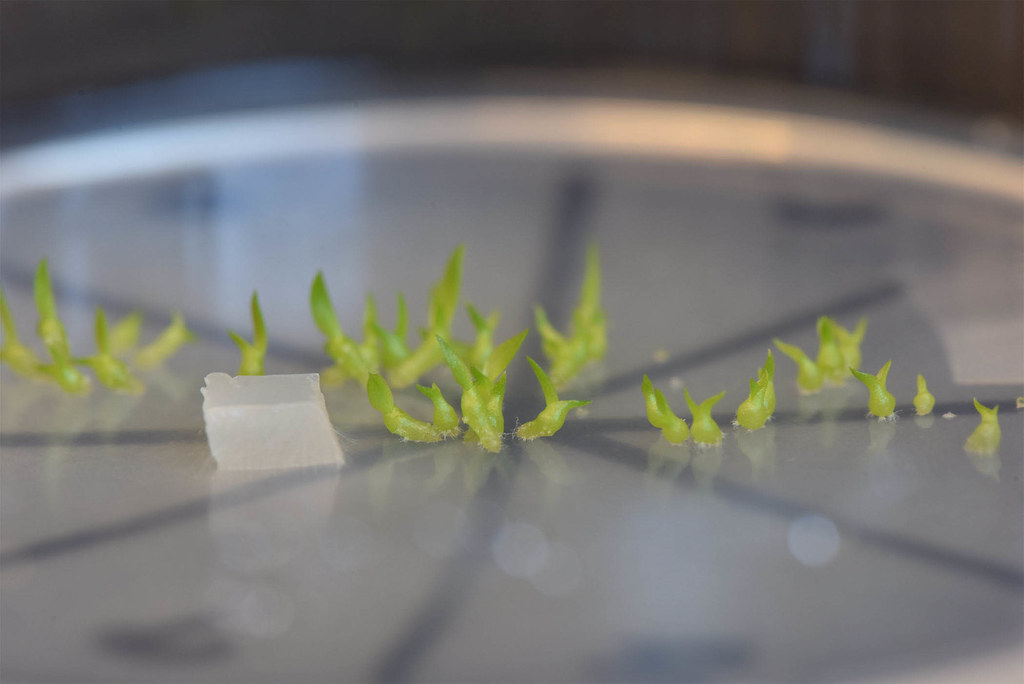

That’s where fungi come into play. Some types of fungi can even germinate several species of orchids, and studying the DNA sequences of these fungi could be vital in the future for endemic endangered orchids and their associated fungi. “I’ve always been interested in relationships between organisms or symbioses,” says Unruh, “the fact that orchid seeds need fungi to survive was too weird not to research.”

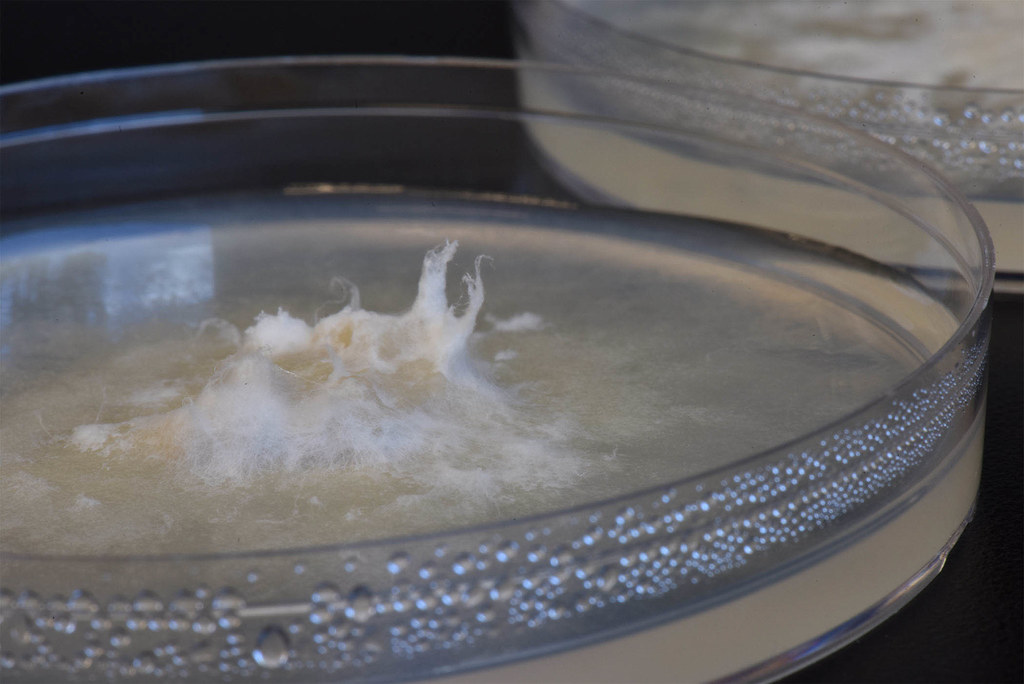

But the process of studying fungi DNA is not a simple one.

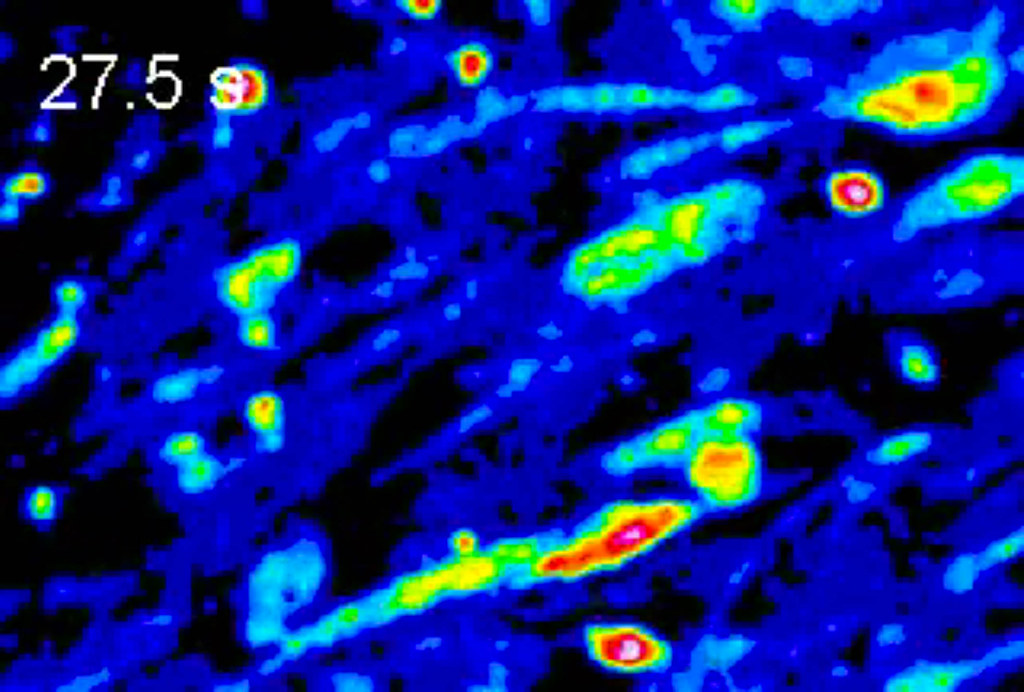

“In order to look at their genomes, I need to grow a lot of fungi and then grind it up and add certain substances to isolate only the DNA. I send this DNA to a facility called the Joint Genome Institute where they send it through a machine that spits out a file with a list of lots of small pieces of the genome – like puzzle pieces. I then use computer programs to put the pieces together and try to assign a function to each gene.”

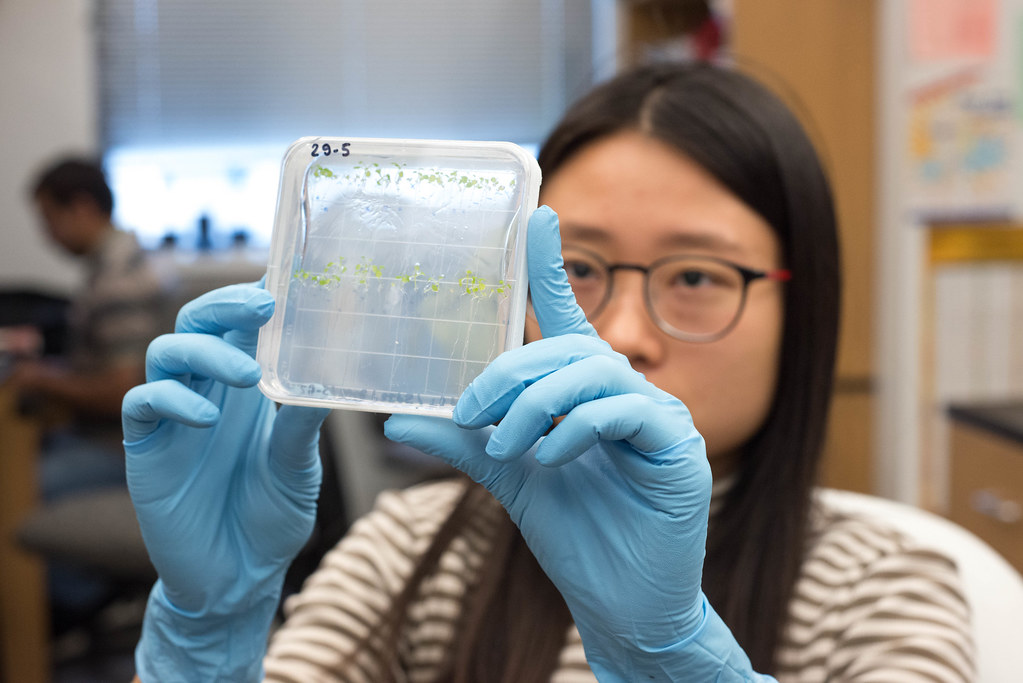

So, the established relationship between fungus and seed helps the orchid, but it’s not known what the fungus is getting out of this arrangement. One idea, based on recent published research, is the fungi receives a certain form of nitrogen from the orchid seeds. Another experiment Unruh is working on is growing the orchid seeds by themselves through special media, growing the fungus by itself, or growing them together. She then measures the gene expression to see if there are big differences when the plant or fungus is alone or together. “This will help answer my question of how mutually beneficial this association is,” says Unruh.

The data collected from this research will form the bulk of her PhD thesis. However, there remains many questions regarding the relationship between orchids and fungus that Unruh would like to explore in the future, such as which fungi are best for reintroducing endangered orchid species or what other roles fungi play in their environment. “I foresee fungi, especially plant and fungal relationships, becoming the focus of more and more research in the future.”

In 2014, Unruh received a three-year National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship. More recently, she has received a grant from the Joint Genome Institute to sequence 15 full genomes of orchid fungi.