By Lauren Hines | Bond LSC

Shaking a bad rap can be hard.

However, the Ron Mittler lab at Bond Life Sciences Center has shifted the scientific community’s thinking from seeing reactive oxygen species (ROS) as destructive to vital.

“It’s always a challenge when you do something for the first time, and people don’t always believe you,” said Mittler, principal investigator. “They want you to prove it.”

ROS are reactive molecules that perform chemical reactions easily. While these molecules cause destruction in cells with these reactions, they can also send widespread messages and regulate many essential processes. However, this benefit of ROS wasn’t always known.

Back in the Day

In the 1980s, the scientific community recognized ROS as important. But according to Mittler, the community also thought ROS only offered destruction to human cells and caused aging.

“All this is not true,” Mittler said. “It’s not that simple to just say that, but there was a big hype about reactive oxygen species being painted as the bad boys of biology, and so forth.”

Then, in 2009 Mittler discovered the ROS wave.

This wave fills in the communication gap in plants left by the lack of something like a central nervous system. Instead, plants use the ROS wave and systemic signaling to respond to stresses. ROS triggers a cell reaction in one area of the plant that triggers the cell next to it and so on creating a wave of activation throughout the plant. This way, the plant can acclimate to its environment and is important since plants don’t have the luxury to get up and move when something threatens them.

Mittler was at the University of Nevada in Reno studying responses to ROS. He was originally looking to develop a reporter system to screen for mutants that are deficient in sensing ROS.

“We noticed that we don’t only record local responses that when we treated one single leaf, we got a systemic response, and, from there, using additional experiments, we developed the ROS wave concept,” Mittler said.

Mittler published his new discovery in Science Signaling, and more papers came, exploring systemic signaling and similar processes, highlighting the importance of the ROS wave to many biological responses.

“Slowly people started to realize that reactive oxygen species are actually important, and they’re doing a good thing,” Mittler said.

What’s Happening Now in the Lab

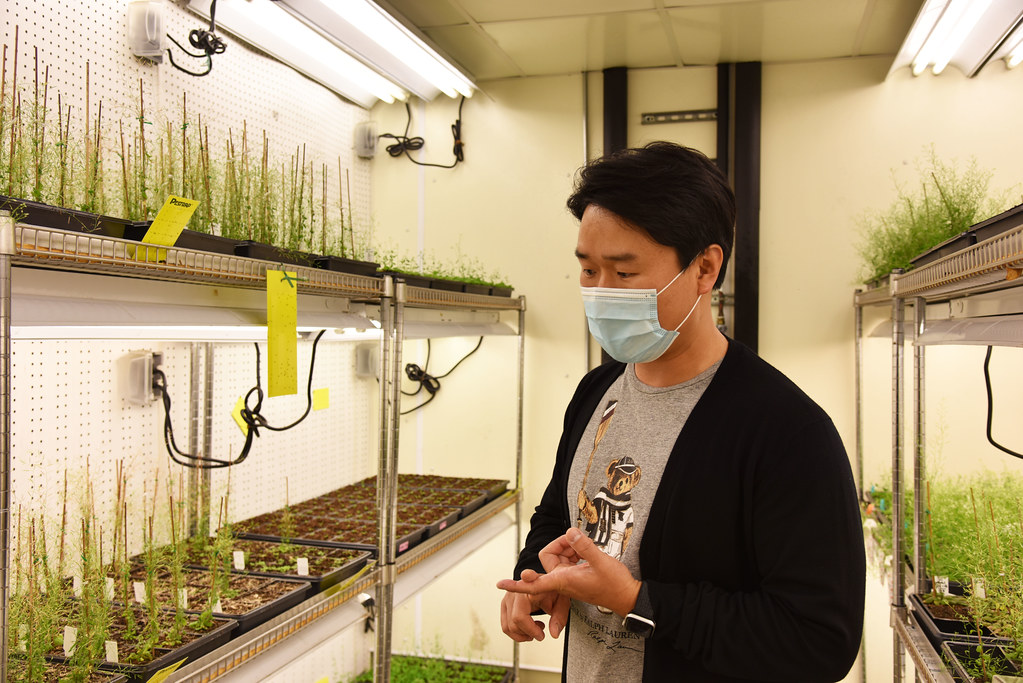

More than 10 years down the road, Mittler still focuses on ROS. Current Mittler lab post doctorate fellow Yosef Fichman, has taken the baton in the study of ROS waves.

“I was born to a family that was working in agriculture, and my father grew oranges in Israel,” Fichman said. “For a farmer or a person working in agriculture, life revolves around growing plants 365 days a year. In a way, I was always fascinated by plants.”

Fichman and others in the lab have been working towards finding more pieces to the process.

“There is a cliché that says proteins never work alone, so we’d like to know which other ingredients are involved,” Fichman said. “In my latest paper, using mutant plants, we were able to detect more ingredients to this mechanism and expand our knowledge.”

Fichman and others in the Mittler lab worked to image the ROS wave, tested different stresses for the ROS wave to respond to and found more pieces to the puzzle. Fully understanding this process can help researchers eventually create genetically modified crops that withstand more stresses.

What There’s Left to Discover

Currently, researchers don’t know exactly which compartment of the cell is most important in regulating this process or if compartments interact with each other. They also don’t know how it all results in gene expression or how different waves interact with each other and work together.

“There’s a lot to learn because we know that if we just look at this from the narrow window of the ROS wave, we know that it’s important,” Mittler said. “If you don’t have the ROS wave, the plant cannot acclimate properly.”

Though Mittler lab researchers have been hard at work for the past few years dissecting this process, it’s unlikely they’ll stop anytime soon.

“In a way, it’s harder to publish new ideas, but it’s more exciting,” Fichman said. “We are grabbed by our curiosity and we want to find the answer. We want to find the big answers.”

Find more details about Mittler’s current research in the most recent publication found in the Plant Cell journal.