When Chiemerie Azubuogu announced his new position in the Bond Life Sciences Center on his LinkedIn page, he thought back to when he first came to the U.S. from Nigeria eight years ago.

“If I get into a time machine and go back to that particular date on the 23rd of August 2013 and meet myself there in the airport and tell myself, ‘Hey, in 2020, you have finished your bachelor’s, and you’ll be going to Ph.D. program,’ I’d probably doubt myself like, ‘Man, get out of here,’” Azubuogu said.

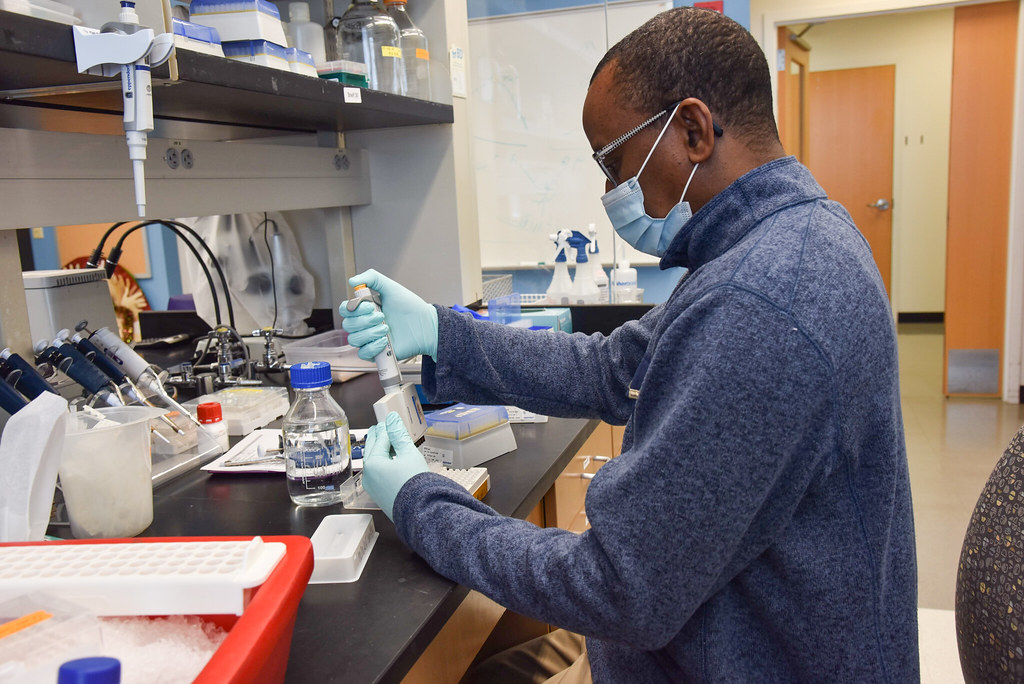

Azubuogu joined the Micheal Petris lab in March as a Ph.D. student.

“This current milestone of mine is one of my proudest moments,” Azubuogu said. “I know there are a lot of them to come, but I just treat every milestone as one of my proudest.”

Azubuogu gravitated towards the Petris lab during his rotation through the labs on campus because of its unique approach to cancer research looking at the intrinsic requirement for copper in tumorigenesis and metastasis.

Copper is a trace mineral in the body that helps with forming red blood cells, brain development and other vital processes. While normal cells take in copper, tumor cells grown in mice have a much higher copper uptake. The Petris lab aims to target this vulnerability to kill cancerous cells.

“What I’ve experienced with [cancer research] is either developing targeted radiolabeled particles against biomarkers on cancer cells which binds and kills the cancer cells, or you can develop imaging agents used for cancer diagnosis, but I haven’t approached the problem as looking at those nutrients that provide nourishment for the cancer cells,” Azubuogu said.

His drive toward cancer research began when he was growing up.

“Nigeria is still a developing country,” Azubuogu said. “We have a lot of stuff going on. A lot of development is happening, but there are still some shortcomings, especially in the healthcare sector.”

Azubuogu said these shortcomings involve a lack of hospital facilities and diagnostic equipment, among other things.

“I would say [I have] a passion in me to try to get into the workforce to try to address those issues,” Azubuogu said. “I just really want to contribute to the field of healthcare or medicine or science.”

His broad ambition narrowed when he was an undergraduate at the University of California in San Diego. He didn’t know whether to go into drug manufacturing, diagnostics or medicine. His mentor at the time, Dr. Schmid-Schönbein, steered Azubuogu towards research.

“He put me on the path of actually exploring research…during my orientation at UCSD, he told me that ‘As a researcher, you can enable thousands and thousands of doctors to save lives,’” Azubuogu said.

He found his niche in cancer research because of its global presence and the healthcare issues in Nigeria.

Azubuogu’s journey to this point hasn’t been an easy one. Obstacles like waiting more than six years for a visa, working as an independent student and dealing with the inferiority complex that comes with being a minority in STEM challenged him.

He credits his ability to overcome these obstacles and his success to his support system of research mentors and family.

“One of my proudest moments I have witnessed and one of the moments that encourages me the most is watching [my father] step up to receive his doctorate,” Azubuogu said. “He was able to achieve that feat while still taking care of his family and working full time.”

Azubuogu said his father had to give up his education to get into an apprenticeship at a young age to help his parents and siblings. Though his father loved education and learning, he never had the opportunity to pursue an education in Nigeria.

When Azubuogu’s father came to the U.S. in the early 2000s, he pursued his passion for education, starting with evening adult classes at a nearby high school. When Azubuogu and his three siblings came to the U.S., his father was working on his doctorate, which he received in 2016.

“No matter how much I work, I’m not going to work as much as my father, who took care of a family of five, and he still got his doctorate,” Azubuogu said. “It kind of makes me draw more inspiration from that and it just keeps me going.”

While Azubuogu will be at Bond LSC for at least five years, he plans to join a biotech or biopharmaceutical company after graduating. He also envisions himself going back to Nigeria to help with cancer diagnoses and therapeutics research with the hope of someday establishing his own biotech company in Nigeria.