The difference between walking and being paralyzed could be as simple as turning a light switch on and off, a culmination of years of research shows.

Recently, University of Missouri Assistant Professor of biology Samuel T. Waters isolated a coding gene that he found has profound effects on locomotion and central nervous system development.

Waters’ work with gene expression in embryonic mouse tissue could shed light on paralysis and stroke and other disorders of the central nervous system, like Alzheimer’s disease.

Waters works extensively with two coding genes called “Gbx1” and “Gbx2”. These genes — exist in the body with approximately 20,000 other protein-coding genes — are essential for development in the central nervous system.

“To understand what’s going wrong, it’s critical that we know that’s right,” Waters said.

Coding genes essentially assign functions for the body. They tell your fingernail to grow a certain way, help develop motor control responsible for chewing and, as shown in Waters’ research, help your legs work with your spinal cord to facilitate movement.

Waters and his researchers, including graduate student Desiré Buckley, investigated the function of the Gbx1 by deactivating it in mouse embryos and observing their development over a 18.5-day gestation period — the time it takes a mouse to form.

The technology could eventually contribute to developing gene therapies for paralysis that happens at birth or from a direct result of blunt trauma, like a car accident.

“Understanding what allows us to walk normally and have motor control, allows us to have better insight for developing strategies for repairing neural circuits and therapies,” Waters said.

Technology for isolating genes and their functions

Waters studies embryonic mouse development. To understand certain gene functions, he inactivates different genes using a technology called “Cre-loxP.”

Genes can be isolated, then inactivated throughout embryonic tissue. Many of Waters’s studies inactivate genes to harness a better understanding of which genes are responsible for what.

“The relevance of it to the well-being of humans, is apparently relevant to development and more importantly to the development of the central nervous system,” Waters said. “Now it’s taking me to the point where we’re getting a bird’s eye view of what’s actually regulating our ability to have locomotive control.”

No Gbx1, no regular locomotion

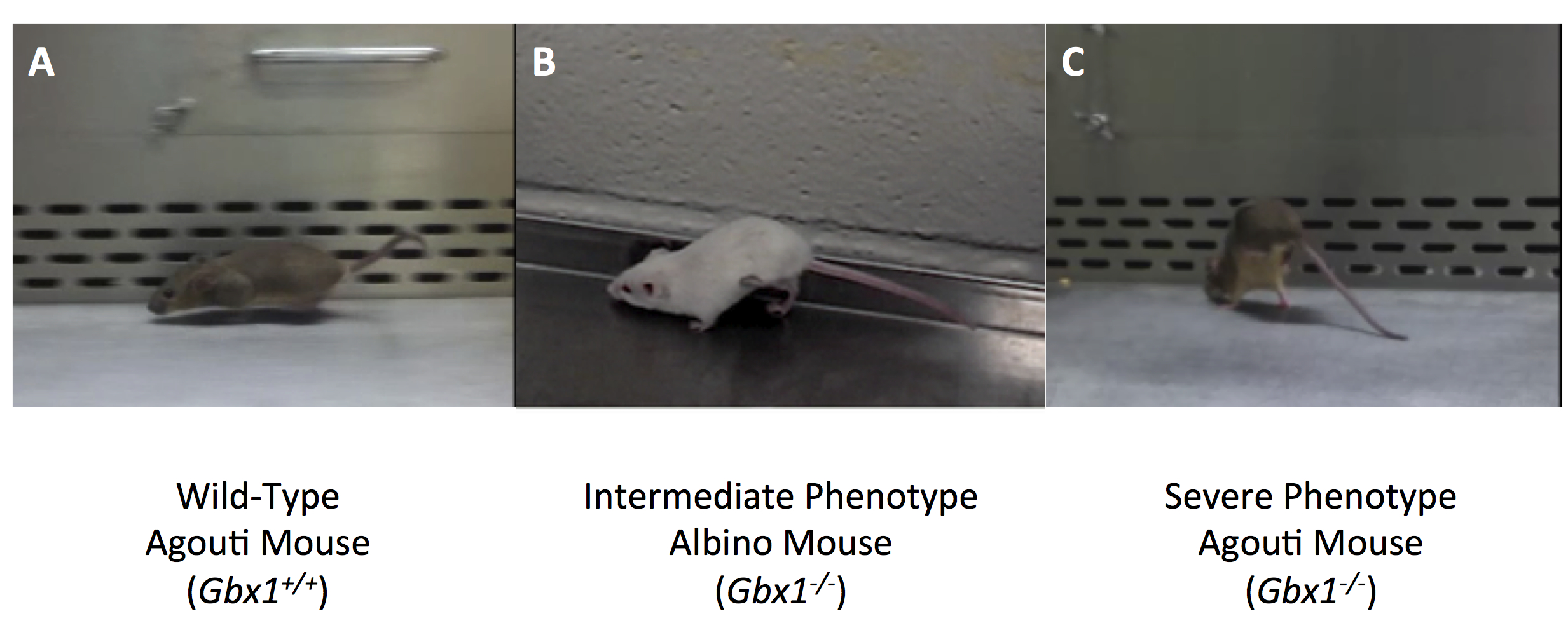

Mice that Waters uses in his lab, “display a gross locomotive defect that specifically affects hind-limb gait,” according to their article published in Plos One, February, 2013.

In contrast to its family member Gbx2, when Gbx1 is inactivated, Waters concluded, the anterior hindbrain and cerebellum appear to develop normally. But neural circuit development in the spinal cord —- what allows us to walk normally —- is compromised, he said. According to an article published by

Waters, November 2013, in Methods in Molecular Biology, this occurs despite an increase in the expression level of its family member, Gbx2, in the spinal cord.

A video recording from the research, which was funded by the National Science Foundation and start-up funds from MU, show the mouse with the Gbx1 held back, with an abnormal hind-limb-gait.

Mice with this inactivated gene were otherwise normal, Waters said.

“If they were sitting there without moving, you wouldn’t know anything was wrong with them,” Waters said.” They’re able to mate, eat and appear to function normally.”

No Gbx2, no jaw mobility

When Gbx2 function is impaired in the mouse, Waters observed that development of the anterior hindbrain, including the cerebellum, a region of the brain that plays an important role in motor control, didn’t form correctly.

The mice, as a result, cannot suckle, so they die at birth, Waters said.

“We’re getting a better insight into the requirements for suckling — another motor function required for our survival,” Waters said.

The research has paved the way for investigating other coding genes and their responsibilities and roles in development, Waters said.

“We have a lot to do still,” Waters said. “So, why am I so excited about it? That’s part of the reason.”