By Paige Blankenbuehler

Lauren and Claire Gibbs share contagious laughter, ambition and a charismatic sarcasm.

Both are honor students at Shawnee Mission East High School in a Kansas City suburb.

They also share a neuromuscular disease called spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), designated as an “orphan disease” because it affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.

However, the landscape for individuals with SMA is quickly changing with the development of new drugs.

More than 7 million people in the United States are carriers (approximately 1 in 40) of the so-called “rare” neurodegenerative disease, SMA.

Faces of SMA

The success of therapeutics in lab experiments provides a new layer of hope for individuals and families living with the disease.

Lauren, now 17, fit the criteria for SMA Type III, while Claire, now 16, showed symptoms of a more severe manifestation of the disease, SMA Type II.

Lauren and Claire Gibbs were diagnosed on the same day.

Despite their numerous similarities, the biggest disparity between them is mobility.

Claire uses a power wheel chair while Lauren is able to use a manual chair. It’s not unusual to see Lauren being pulled along in her chair, playfully hanging onto the back of Claire’s motorized chair.

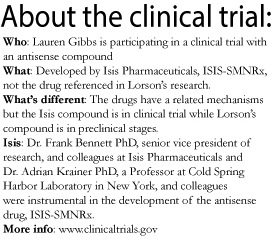

Lauren is participating in a clinical trial with ISIS-SMNRx a compound developed by Isis Pharmaceuticals, a leading company in the antisense drug discovery and development based in Carlsbad, Calif. Lauren feels that she has gained stamina and a greater ability to walk — a feat that wasn’t routine just five years ago.

Prior to the trial, Lauren was able to walk only for short distances.

Bringing New Hope

A new experimental drug developed by researchers at the Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center, is bringing hope to individuals with the orphan disease affecting one in 6,000 people.

Christian Lorson PhD, investigator in the Bond Life Sciences Center and Professor of Veterinary Pathobiology at the University of Missouri, has been researching SMA for seventeen years and has made a recent breakthrough with the development of a novel compound found to be highly efficacious in animal models of disease. In April, a patent was filed for Lorson’s compound for use in SMA.

Lorson’s therapeutic, an antisense oligonucleotide (a fancy name for a small molecule therapeutic that falls under the umbrella of gene therapy), repairs expression from the gene affected by the disease. The research was published May in in the Oxford University Press, Human Molecular Genetics.

The drug developed by Lorson’s lab is conceptually similar to ISIS-SMNRx already in clinical trial developed by Isis Pharmaceuticals and a team of investigators at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory headed by Dr. Adrian Krainer.

Antisense drugs are not a new practice, but their wide-spread adoption seems to be on the cusp with recent success stories like the commercialization of an FDA-approved antisense compound produced by Isis in 2013 called Kynamro for the treatment of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, a high cholesterol disorder that is passed down through families.

Science behind success

The National Institutes of Health has listed SMA as the neurological disease closest to finding a cure. Discoveries made by the Lorson Lab have contributed significantly to current scientific understanding of the disease mechanisms and to the advances being made in finding an effective treatment for SMA.

These antisense therapies work because of the genetic makeup of SMA —the genetics are incredibly clear: a single, specific gene called Survival Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1) has been pinpointed as the cause of SMA.

SMA is a neurodegenerative disorder, meaning muscles become weaker over time due to sick or dying neurons.

These neurons become less functional because of low levels of the SMN.

Remarkably, the disease can be reversed in animal models of disease if the nearly identical duplicate gene, SMN2, can be “turned on” to compensate for low SMN levels.

Lorson’s antisense oligonucleotide therapeutic provides incredible specificity because it hones in on a specific genetic target sequence within SMN2 RNA and allows proper “editing” of the RNA encoding the SMN protein. The strategy is to “repress the repressor,” Lorson said.

The SMA-specific defect lies at the RNA step – the “cutting and splicing” of important RNA sequences does not happen efficiently in SMN2 RNAs because of a several “repressor” signals.

“The final chapter of the book — or the final exon — is omitted,” Lorson said. “But the exciting part is that the important chapter is still there – and can be tricked into being read correctly: if you know how.”

The new, antisense oligonucleotide seems to know how to get the job done.

The existence of such similar genes as SMN1 and SMN2 in humans creates a rare genetic landscape lending itself especially to a therapeutic development for SMA.

Humans are unique in this duplication — something Lorson calls a “genetic happenstance” that, on an evolutionary scale, may as well have happened yesterday.

Why humans have developed this redundant gene is unknown.

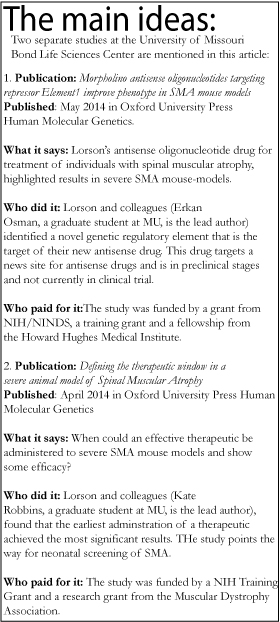

Thalia Sass, an MU biological sciences major, genotypes samples in the Lorson Lab where spinal muscular atrophy is researched.

Timing is everything

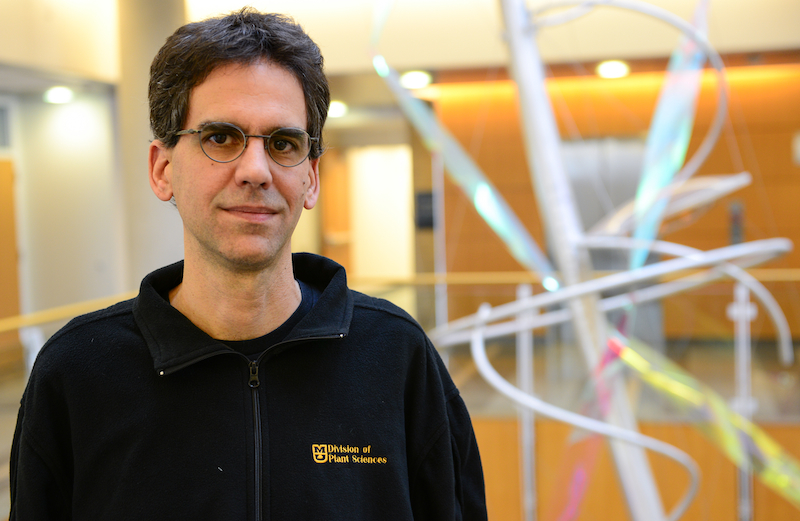

In addition to the developments of new SMA therapeutics, Lorson and his lab sought to answer an important biological question concerning the disease: When can a therapeutic be administered and still show some degree of efficacy?

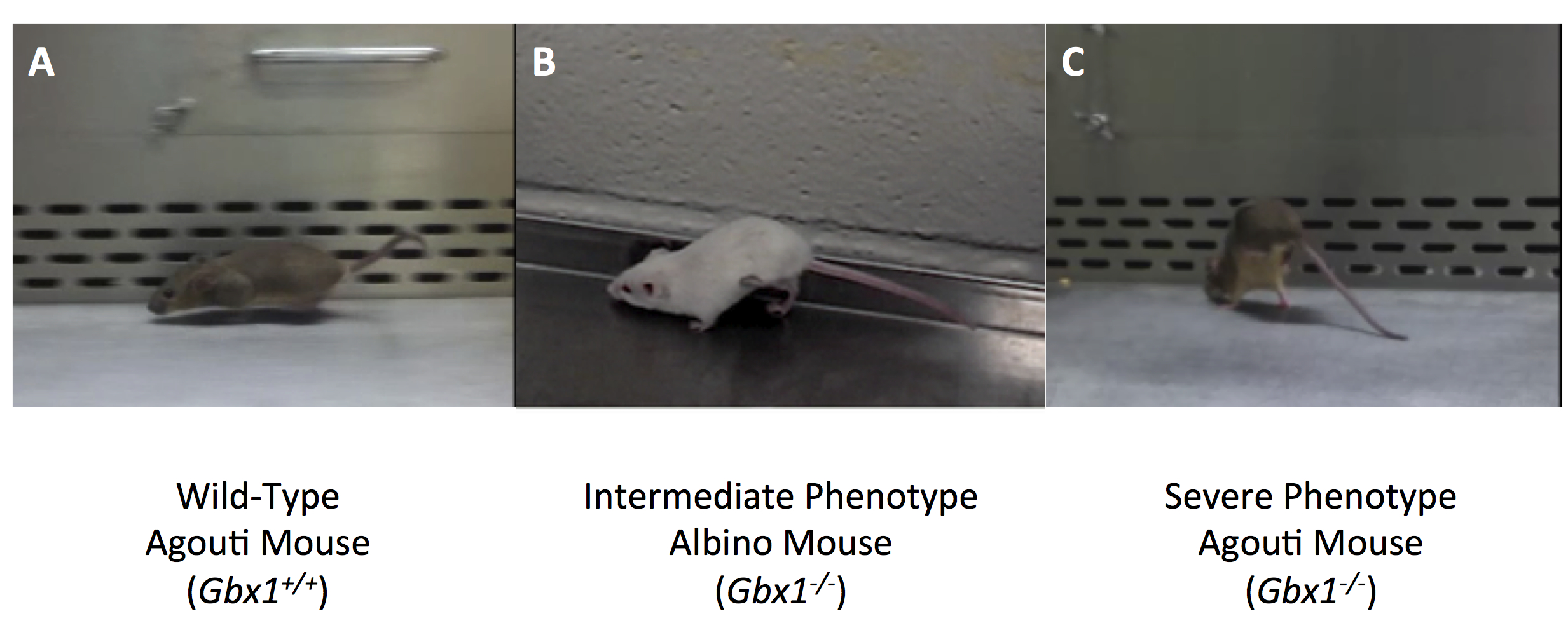

Lorson’s research found that the earliest administration of a treatment provided the best outlook— extending the survival of laboratory mice by 500 to 700 percent, “a profound rescue,” according to his research published in April in the Oxford University Press, Human Molecular Genetics.

A near complete, 90 percent rescue was demonstrated in severe SMA mouse models. But even when the therapeutic was administered after the onset of SMA symptoms, there was still a significant impact on the severity of the disease.

“If you replace SMN early and get (a therapeutic) to cells that are important to the disease, you correct it,” Lorson said. “This provides hope that patients who have been diagnosed will still see some therapeutic benefit even if it is clear that the best results will likely come from early therapeutic administration.”

In Lorson’s study it’s definitive that the earlier a therapeutic can be administered, the better the outcome for individuals with SMA.

“This really points towards a strong push for neonatal screening,” Lorson said. “Infant screening would likely be incredibly beneficial for SMA and that’s something that the SMA community is really excited about.”

A breakthrough for families

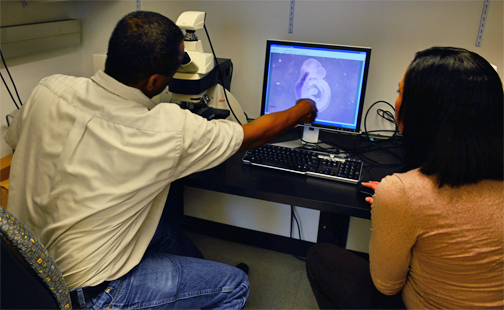

On June 2, Lauren and Claire Gibbs attended a routine, annual rehab appointment with Dr. Robert Rinaldi, MD, division of pediatric rehabilitation medicine and attending physician at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo Dr. Rinaldi is not associated with the Isis clinical trial.

The appointment was like a reunion among close friends — Rinaldi began seeing Claire and Lauren Gibbs 16 years ago, the first year that he began working at the hospital and when the girls were one- and two-years-old, respectively.

The girls did all of the routine tests —measuring strength of grip and breathing, and assessing range of movement with the occupational and physical therapists.

A little later, Rinaldi sat with Natalie Gibbs, Lauren and Claire’s mother and a relentless advocate for advancement in SMA awareness.

Typically the muscles of individuals with SMA deteriorate over time, but together they inspected the definition of a new calf muscle on Lauren’s left leg.

For a young woman with Type III SMA — this means she can walk for short distances with little discomfort but still uses her wheel chair a majority of the time — Lauren’s new calf muscle is a remarkable achievement.

As Lauren continues to participate in the ISIS antisense therapy clinical trial, her conditions continue to improve dramatically, even with the late administration of the therapy — in her case, 16 years after her diagnosis and onset of effects.

As Lauren continues to participate in the ISIS antisense therapy clinical trial, her conditions continue to improve dramatically, even with the late administration of the therapy — in her case, 16 years after her diagnosis and onset of effects.

Lauren believes her ability and stamina for walking have increased significantly.

“Quite frankly my jaw almost hit the ground when she stood up — the change was that impressive to me,” Rinaldi said.

Rinaldi, also the co-director of the Nerve and Muscle Clinics at the hospital, had last seen Lauren two years ago. He said the Lauren he saw during a routine rehab appointment in June was like seeing a new person altogether.

“The way she stood up from the wheel chair — how quickly she did that with no support — her posture when she was standing up was more upright, her pelvis was in a much better position, her core was straighter,” Rinaldi said. “It struck me immediately how much better she looked.”

Lauren Gibbs is the first of Rinaldi’s patients to have participated in the ISIS clinical trial.

“It’s moving very fast in this field,” Rinaldi said. “I think the technology that’s evolving in research is opening up more avenues for investigation for us and there’s a big desire to find a cure for these types of diseases.”

The progress has rewarded the Gibbs family’s advocacy in SMA awareness and they’ve been able to set new goals they didn’t imagine were possible when the diagnoses for Lauren and Claire were made. Natalie Gibbs is a long-time member of Families of SMA and is currently on their Board of Directors.

The organization Families of SMA is currently providing funding to Lorson to advance this research area.

“We’re able to see first hand — and our physician who has been watching them for sixteen years has seen — that everything we’re doing in the clinical trials is really making a difference,” Natalie Gibbs said.

Over the course of their daughters’ lives, Natalie and her husband Tim Gibbs say a shift in momentum has accelerated the technology and research toward finding a cure for SMA.

“I am really impressed with the progress Lauren has made with the trial and how well Claire is doing overall,” Natalie Gibbs said. “Even though it’s a progressive and very devastating type of disease, I feel like we’re really conquering it.”

Link to publications:

Therapeutic window study: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24722206

University of Missouri ASO: http://hmg.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/04/29/hmg.ddu198.full.pdf+html

For more information on spinal muscular atrophy, visit FightSMA.org and fsma.org